Why Haydée?

“ . . . the mere mention of Haydée Santamaría signifies a world, an attitude, a sensibility, and also a Revolution, which she did not conceive of as confined to the land of José Martí but to the future of all our peoples.”

—Mario Benedetti[1]

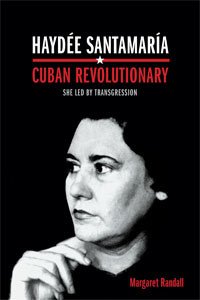

Haydée Santamaría was a heroine of the Cuban Revolution, a brilliant, strong but unassuming woman among powerful men. One of only two females among 160 males, she helped organize and fought on the front lines of the 1953 attack on Moncada Barracks in Santiago de Cuba. Following that first military operation, when she was captured and shown her brother’s eye and lover’s mangled testicle to make her divulge information about their Movement she replied: “If you did that to them and they didn’t talk, much less will I!”

Haydée—like Fidel, all who knew her called her by her first name—was a provincial woman who had never before left her island country. Yet during the revolutionary war she found the courage to travel to the United States, organize its Cuban community, and buy weaponry from Mafia thugs. After that war was won, and despite growing up in a small rural village and never having gone past sixth grade, she founded and ran the most important cultural institution in Latin America; drawing artists and intellectuals such as Violeta Parra, Jean Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Laurette Séjourné, Julio Cortázar, Eduardo Galeano, Ernesto Cardenal, Idea Vilariño, and Gabriel García Márquez to visit and satiate their curiosity about that small nation with enormous dreams.

Haydée conceived of change and participated in actions—military as well as political—beyond those accessible to the vast majority of women in her time and place. She took enormous risks and avoided detection with an uncanny calm and remarkable talent for deception and disguise. She was one of the founders of Cuba’s July 26 Movement and later its Communist Party (PCC), remaining at its highest levels of leadership throughout her life. Yet she had no interest in the positions of power such membership bestowed. She led by transgression.

In her work at Casa de las Américas Haydée rendered ineffective the cultural blockade the United States tried so hard to establish along with its diplomatic and economic counterparts, and protected and encouraged more than a few creative spirits persecuted during repressive periods in Cuba’s revolutionary history. She was a courageous innovator, deeply sensitive to the needs of others, a bountiful mother, and warm friend.

Her life was also rife with contradictions. When she committed suicide, at the age of 57, Havana historian Eusebio Leal eulogized her saying: “Haydée was Moncada’s last victim.” I prefer the word casualty. Haydée was not someone who allowed herself to be victimized by anyone or any circumstance. Yet she lived with profound loss and grief. There was Moncada, where she lost the two people she loved most—her brother Abel and fiancé Boris Luis Santa Coloma—and whose experiences of brutality and sadism accompanied her for the rest of her life.

There were other losses as well: Che Guevara, with whom she shared the dream of Latin American liberation. Celia Sánchez, perhaps the only other woman who understood her completely and whose deep friendship helped her stand tall in a world of men. Other close friends, whose lives were cut short for one reason or another. Colleagues who abandoned the revolutionary project. And some dreams of social change that never came quickly or permanently enough for her vision of immediate justice.

Justice, Revolution, loyalty: these were her mantras. Depression ran in her family, requiring sensitivity and compassion. Betrayals, of close comrades as well as ideals, pained her to the core. Armando Hart Dávalos, fellow revolutionary and the man she married after losing Santa Coloma, gave her a son and daughter and for a while provided love and stability. Together they parented their biological children as well as a number of others, orphans from Latin American revolutionary struggles. When Hart left her, suddenly and without discussion, it was an additional blow. Just like Revolution, marriage was forever in her worldview.

She was plagued by depressive episodes and periodically took to her bed in despair. Today we understand more about depression than we did back then: how debilitating it can be and what courage it takes to confront its ravages. Yet Haydée’s work at Casa and other important projects were more than successful; they achieved a level of excellence and set standards of collectivity few have been able to match. All the children she raised described her as an extraordinary mother. She challenged power wherever and whenever she saw its corrosive damage, and espoused feminist ideas long before the philosophy was accepted in Cuba. She produced and sustained more in the way of creative change than anyone I have known.

***

This is not a biography. I will provide enough data so the reader will have the “facts”: birth, childhood, role in the Cuban Revolution, professional and family life. But my intention is to veer from the confines of traditional hagiography, and probe deeply into the paradoxes, as only someone who trusts intuition as much as reason can. Further developing a genre I began to explore in Che on My Mind,[2] I am interested in looking at tensions and trying to decipher how this woman negotiated multiple contradictions. This is an impressionist portrait, written by a poet rather than a historian. Mine is a rebel and feminist lens. First I want to tell the reader why I have chosen to write about Haydée Santamaría.

I must say upfront that I loved Haydée, loved and admired her as a friend and as an exceptional twentieth century woman: an extremely unique spirit, brilliant intellect, courageous and creative revolutionary, and generous human being. Even in death, she remains a mentor.

I first met her on my initial visit to Cuba in January of 1967. I was living in Mexico City and had been invited to participate in El encuentro con Rubén Darío,[3] hosted by Casa de Las Américas, the exemplary arts institution of which she was the director. That visit to “the first free territory in America” (as we called the country back then) was illuminating in all sorts of ways. But no part of the experience had a more profound or lasting impact than meeting Haydée.

She was a small woman, and ordinary in appearance, some might even say plain. Slightly stooped and with the telltale rise in her chest common to those who suffer from severe asthma, she nevertheless carried herself with a dignity that stopped you in your tracks.

I remember her in simple pants and shirt, sitting on the floor talking animatedly with groups of visitors. And I remember her delighting in a hand-embroidered peasant dress someone had given her. She didn’t flaunt the latest in elegance or fashion, but was vain about her hair, often wrapping her head in a scarf or turban, or indulging in one of several wigs. I imagined these as expedient solutions to bad hair days for someone I doubt had much time for beauty parlors. She always had an inhaler in her hand.

Her piercing hazel eyes didn’t flinch; they grabbed you and held on, sometimes almost accusatory, always inviting. You could lose yourself in those eyes, but might not be able to bear what you found there. You understood that she held you to standards you would find hard to achieve. We all knew her story; the drama she had been forced to endure might have seemed exaggerated or even macabre if she hadn’t been right there in front of you: genuinely interested in every aspect of your life, conversationally at ease and serene.

You sensed she saw through you to a place you yourself might discover years down the road. But it was her voice that made the most profound impression: what she said, and how she said it. She spoke directly, forcefully, clearly, often wandering and seemingly lost until she brought her discourse back to a more linear configuration. What others shrouded in hyperbole she put out there, simply, as if it were the most natural thing in the world. And coming from her it was. You believed her without question, and that proved to be a good idea 99 percent of the time. But you weren’t doing the math, not in her aura. Essence was more important than detail.

Our relationship deepened after I went to live in Cuba in 1969. Like many whose lives she touched, she never became the sort of close friend who frequented my home. Yet we had an immediate and deep connection, and I experienced an intimacy that has remained with me. I remember some of our conversations verbatim. I suspect that almost everyone who crossed paths with Haydée felt a similar connection, for she had an uncanny ability to see, listen, and empathize. Until 1980, when she died and I left Cuba, we shared moments that included formal interviews as well as private conversations. Her suicide still sometimes wakes me at night, bereft and shaking.

***

I have written about Haydée, in several prose texts and poems.[4] The memoir I published about my eleven years in Cuba is dedicated to her.[5] That dedication reads: “To Haydée Santamaría, who took the secrets with her.” I wasn’t referring to those supposed secrets the revolution’s detractors are so quick to imagine must exist, hiding this or that error or betrayal. Neither did I mean purely personal secrets such as those we all keep. I meant a knowing only someone as pure as Haydée possesses and projects quite naturally.

Despite its clichéd connotation, I use the word pure with intention. There are people for whom no other adjective fits. Revolution—great complex social upheavals that turn society on end and, if successful, change the way we relate to one another—are made by all manner of people. They necessarily think outside the box, are courageous, and willing to make enormous personal sacrifice. But, like all humans, they also have their contradictions. Some start out with a vision that bends and erodes as time goes on. Most believe some future end justifies means that fall short of espousing their proclaimed values. When those once engaged in guerrilla warfare must switch gears and manage the affairs of State, certain compromises may become necessary. And there are also those who jump ship at some point along the way, suspicious of an ideological turn, dragged down by difficult times, or unable to continue making do without the creature comforts.

In my lifetime, Vietnam’s Ho Chi Minh and South Africa’s Nelson Mandela have been exceptions, exceptional. Among the many good men and women of the Cuban Revolution, a few embody this purity—a particular combination of innocence, vision, courage, brilliance, creativity, inclusiveness and genuine humility. I think of Fidel,[6] first and foremost. I think of Ernesto “Che” Guevara,[7] Celia Sánchez,[8] and Haydée Santamaría. There are others, of course, but these four names are at the top of my list. I do not mean they are perfect, whatever that may mean, only unwavering in their search for justice and profoundly principled.

Each was his or her own person, shadowed by contradictions, capable of regret or egregious error, perhaps even going down the wrong political path for a time. Each may have hurt others as he or she searched for the greater good. And each was a product of a particular place, time, culture, and historic necessity, bound by those limitations even when reaching beyond them. But all were ahead of the time they inhabited, and ultimately transcended that time, place, culture, and necessity.

I had written about Haydée, but never deeply enough. I hadn’t asked the right questions or ventured enough answers, which is what I hope to do here: bringing my own imaginings to the clues she left. The books and articles written by others unfortunately range from extremely partial to frustratingly superficial. Eulogies at the time of her death and remembrances on its anniversaries are among the most moving testimonies. Her closest associates and family members, including both her biological children, are mostly gone.

In order to create the portrait I hope to bring to life, I traveled to Cuba in April 2014, where I was able to research archives, interview people who had been close to my subject, visit her birthplace and childhood home, and gather material from different sources. Fortunately, I am at a point on my own journey where I consider no hero to be beyond a probing lens. In fact, I understand that only when we are willing to apply that lens will we bring them into the sort of focus that allows an honest exploration of what made them so extraordinary.

***

In Haydée’s case, it helps to be able to go back and understand what life was like for women in Cuba at mid-twentieth century. They inhabited a narrow space and, depending on economic status, education and culture, it might have been narrower still. As a woman, particularly one who lived at a time so constrictive to women’s opportunity and agency, Haydée transcended gender, class, racial, sexual and cultural prisons. She didn’t do this through economic status, formal education, theoretical study, or by spending time deconstructing the hypotheses of her day, though all these played a role. Her childhood on an early twentieth century Cuban sugar plantation had given her a hard look at exploitation, the inequality between the bosses and those who cut the cane or labored in the mill. She was a woman of action, and action informed her ideology as surely as Martí,[9] Marx, Lenin, her younger brother Abel, and Fidel.

She completed only a primary education, at a one-room plantation schoolhouse where a single teacher taught all the grades. Was it common at the time for girls not to seek further schooling, or was there some other reason she didn’t go on to high school and university? What were the educational expectations common to her class and gender? She was certainly bright and curious enough that one would have thought a higher education something she’d have been eager to pursue. From a traditional immigrant family, did she endure pressure to marry young?

In the early 1950s she traveled to Havana with her younger brother, Abel. Several texts emphasize the fact that she went “to take care of him,” the proverbial housekeeper and cook. He as well as she made it clear that this wasn’t the case. He knew she was passionate about social change, and was rescuing her from a conservative and stultifying family life. They were both members of the leftist Orthodoxy[10] enraged by Fulgencio Batista’s 1952 coup.[11] Jesús Menéndez’s[12] organization of sugar workers in their native Las Villas also had had an impact on Abel, and through him on her.

Haydée had long been influenced by her brother’s ideas. In Havana she met his comrades, including Fidel Castro, “that tall guy who flicked his cigar ashes all over my clean floor,” and quickly became involved in their work. She and Melba Hernández were the only women who participated in the July 26, 1953 assault on Moncada Barracks, although other women were active behind the scenes. Abel, and Haydée’s fiancé Boris Luis were tortured to death following the attack. Haydée and Melba survived, were tried, and sentenced to seven months in prison. Fidel and the other male survivors were given much longer prison terms, but released through a general amnesty in 1955.

The attack on Moncada Barracks signaled the group’s appearance on the political map. One hundred sixty rebels took part in that action, which was a military failure but is credited with initiating the armed struggle that would liberate Cuba five and a half years later. Although Haydée was one of the only two women directly involved, her two sisters were also part of their movement. They supported the action but stayed home to be with their parents because it seemed more than likely that many of those taking part would not survive.[13]

During the war against the Batista dictatorship, Haydée did what she had to do, creatively and responsibly. When ordered to travel to the United States to buy weaponry from the Mafia, she reported having been terrified. But she carried out that risky mission and was successful in securing what the rebels needed. Less well known is the crucial role she played in organizing the exile community, dealing with contentious differences and achieving a tactical unity.

She sewed bullets into tiny individual pockets on the undersides of the circle skirts that were popular then; and that’s how she got many of them into Cuba. Back home, she played an active part in preparing the uprising in Santiago de Cuba. And in the Havana underground, when it was her job to send men out to place bombs in strategic locations, she always sent those she knew would hate the task.

Of that experience, she has said:

I think it has to be difficult for people to be violent, to go to war, but you’ve got to be violent and go to war if it’s necessary . . . What you can’t lose in that kind of situation is your humanity . . . When someone had to place a bomb during the war, and in the underground sometimes I was the one who had to decide who was going to do that . . . I always chose the best, the one who had the highest consciousness, the greatest human qualities, so whoever it was wouldn’t get used to placing bombs, wouldn’t get pleasure out of placing bombs, so it would always hurt him to [have to do that].[14]

***

Haydée had an unwavering belief in human beings; she appreciated them in the full range of their identities and possibilities. And she had interesting insights about the differences and interactions among groups and individuals. I remember her once talking to me about meeting Ho Chi Minh on her first trip to what was then North Vietnam. She described his small figure standing at the end of a long room and then watching him walk toward her. “I never knew if Ho Chi Minh was the kind of man he was because he was Vietnamese,” she said, “or if the Vietnamese are how they are because of Ho Chi Minh.”[15] She didn’t need to say more. I pondered her observation for years, and when I myself visited Vietnam it was never far from my consciousness.

Following the end of the Cuban war, in early 1959 Haydée was charged with founding and heading an arts institution, which would do nothing less than break the US blockade. Along with its economic and diplomatic counterparts, the United States had established a cultural boycott in order to isolate and destroy the Revolution. Haydée’s sixth-grade education hardly prepared her for the complexity or subtleties of the job. She had never been to college, never studied art or literature, but carried out that endeavor brilliantly, making Casa de las Américas a place where the world’s greatest creative spirits felt at home. Because of her legacy, it continues to be such a place.

She looked the world’s great artists and intellectuals in the eye, noticed and remembered their most intimate concerns, and gave so generously of herself that they fell instantly in love. And she was open to all their expressive manifestations. Within Cuba itself, her vision enabled her to see talent in those who were spurned by Party hacks or misunderstood by correct-liners who preferred the safety of mediocrity to the uncertainty of the new. Without her patronage, the innovators of La nueva trova (New Song Movement) would not have become who they are today.[16] She sought artists and writers from among the most marginalized populations. She respected non-conformity and embraced authenticity. Inclusivity was natural to her. She resisted the clichéd Socialist Realist art that was being promoted in the Soviet Union. She listened, paid attention, and learned.

I don’t mean to give the impression that Haydée disparaged Party discipline or refused to go along with the leadership’s decisions. She was part of that leadership, although without relinquishing her integrity, individuality, or capacity for criticism. She was as disciplined and loyal as the best of them, but never unquestioning. Whenever and wherever she saw injustice, she challenged it. Her ability to walk a courageous but fragile critical line, especially as a woman, is one of her attributes that most interests me.

***

Another aspect of Haydée’s thought process that excites my mind was her complex relationship to nationalism. I believe nationalism to be one of the most troubling tendencies of our time, provoking racist or xenophobic policies and justifying terrible crimes (such as genocide in its most extreme form).

An island is always besieged territory, and Cuba is no exception. A small island can and often does become a political football. Throughout its history, Cuba has been invaded, appropriated and occupied by one major power after another. A heavy dose of nationalism was certainly necessary for Fidel and his revolutionary movement to win the support needed to liberate the country. Haydée, too, embodied this feeling. She often talked about Cuba’s sun, beaches, and royal palms, saying that for those three things alone it was worth waking each morning. She had such a profound love of homeland, in fact, that after the amnesty of 1955 she refused to leave with her comrades for Mexico; in her own words, she was afraid she “might not be able to come home.”

Yet Haydée’s work at Casa involved honoring other lands and their artists, making room for their work and their ideas within the Cuban paradigm, and—precisely because she was working with a group of people known for their creative idiosyncrasies—learning to understand and respect other cultures and ways of being in the world. This is antithetical to extreme nationalism. It provides a balance, and I think in time came to temper the rough edges of the Cuban nationalism she too had embraced.

What she created at Casa was a model that the country’s other institutions respected, and some tried to emulate. The way Haydée positioned herself, the way she used what she learned from the world’s artists to enrich the Cuban experience, offers a great deal to be analyzed and understood. In Cuba, the revolution’s generous internationalism also provides a counterpoint to what might have remained a highly nationalist experience. Cold War tensions certainly favored the latter, but Fidel and the Cuban Communist Party emphasized the importance of the former.

Cuba’s participation in Angola and other African battlefields began in 1975, five years before Haydée’s death. She was fervent in her support of those campaigns. The schools for foreign students that existed on Isle of Youth (formerly Isle of Pines) also excited her imagination; students from some of the poorest and most war-ravaged countries studied there without cost. And the Revolution made sure their cultural traditions accompanied them—in memory and relationships, music, art and native foods.

During Chile’s short-lived democratic Revolution in the early seventies, there was a great deal of collaboration between the two countries. Nicaragua’s Sandinista Revolution was victorious just a year before Haydée died, and she traveled there in her last months, so she also knew first hand about the teachers and doctors and other specialists Cuba sent to that Central American nation. One of them was a niece.[17] She would not live to see the crucial aid Cuba gave to other parts of Latin America and the world. Still, at Casa and throughout the Revolution in broader terms, she breathed and contributed to the internationalism that remains one of its defining features.

***

Haydée never let gender discrimination diminish her, or prevent her from doing what she knew she had to do. Which is not to say that many of her male comrades didn’t regard her with the kind of pseudo respect with which they treated women—back then and still. To a disappointing degree this formalistic approach to gender equality continues to exist—in Cuba and almost everywhere. In her personal life, Haydée went to elaborate lengths to try to make the point that gender discrimination is unjust.

She was also conscious of racial inequality. She spoke about how she was criticized as a child for befriending the Black children in her community. Cuban filmmaker Gloria Rolando has spoken about the difficulties in getting her documentaries about Cuba’s Black history exhibited, but says Casa de las Américas always supported her work.[18] This, as well as the fact that there are so many more people of color heading departments at Casa than are visible in revolutionary leadership overall, is a testament to Haydée’s legacy.

Upon her death, because she chose suicide and despite an exemplary revolutionary life, the Cuban leadership failed to honor Haydée as she deserved. For years, at least in certain quarters, you could sense a palpable discomfort around the fact that she took her own life. Some silently accused her of cowardice, some felt betrayed, some simply did not know what to do with their complex emotions, and many short-changed her memory in different ways. Those who worked with or were otherwise close to her, mourned but were powerless to buck the conservative current. In recent years this situation has changed. Suicide does not provoke such blanket condemnation, and Haydée’s undeniable luminosity has sparked a degree of reconsideration. Still, the memorial she deserves has yet to materialize.

Haydée had been a founding and highly valued member of a clandestine revolutionary organization, The July 26 Movement, previously Moncadistas, as many of those involved in that first action called themselves. Later she was one of the initiators of the Cuban Communist Party. She served on its Politburo and remained on its Central Committee until her death. Yet she did what her brother Abel asked of her first, and later what Fidel instructed. Until taking on Casa de las Américas, she followed rather than led. And even during her tenure at Casa, she was subject to the larger political apparatus. At the same time, and often at great personal risk, she never toed a strict Party line, nor could she abide the bureaucracy inherent in such organizations.

From Moncada on, she participated in many of the revolution’s pivotal moments. She was imprisoned following that action, and when she was released from prison played a major role in disseminating Fidel Castro’s defense speech—the programmatic text that came to be known as “History Will Absolve Me.” She held leadership roles in both the Santiago and Havana underground movements, and traveled outside the country to buy arms. She was indispensable on several fronts yet never, during the insurrection or following victory, achieved high military rank.

In 1967 she presided over the internationally important Latin American Organization for Solidarity Conference (OLAS), held in Havana. She was always one of the Cuban Revolution’s few exceptional women; in close to sixty years their number has grown but it has yet to approximate the clear dominance of men.

For too many of those years the Cuban hierarchy considered feminism a dirty word. Even, or perhaps particularly, its mass women’s organization, the Federation of Cuban Women (FMC), disparaged the philosophy. The Cuban Party subscribed to the International Communist dictum that gender analysis would divide the working class and weaken the unity necessary to confront outside threats.

Haydée knew instinctively that this was wrong. Although she didn’t refer to herself as a feminist, she was open to, and appreciative of, feminist ideas. I had an experience with Haydée that illustrates her concern for the degradation of women. In 1970, soon after I moved to the island, she asked me to help judge the yearly pageant to choose a carnival queen and her two attendants. I was appalled. I hated such contests and couldn’t imagine validating them with my presence. But if Haydée asked, I couldn’t say no.

Distraught at the task before me, I wrote a short text about why beauty pageants have no place in Revolution. When the event was over, I handed it to a reporter from the official PCC newspaper, Granma. The next morning it appeared on its front page. Several years later, when I finally had the opportunity to ask Haydée why she had subjected me to such discomfort when she could have made any man’s day by sending him, she replied: “Because I knew you would hate it, and find a way to help us put an end to such affairs. Which you did, as I remember, with your excellent article!”

***

Haydée’s authenticity and loyalty encouraged her to take chances. She was seldom wrong, but often disappointed. She rarely spoke ill of anyone. I think now of the months before her death, when 125,000 Cubans fled the island en masse and those who stayed subjected them to epithets, psychological and even physical violence. How she must have hated those displays of vitriol and pseudo patriotism! Looking back, I am sure that the whole Mariel exodus must have caused her a terrible sadness. Could she have felt overwhelmed by this evidence of social revolution’s crass underbelly?

When a close associate left the country, she was shattered; unless you were as convinced as she was that devotion to the Revolution was the highest human calling, it must have been difficult to work with her. Yet her colleagues have written volumes about that privilege. They speak of the enormous attention she paid each detail of what went on at the institution, and about her far-ranging eye and profoundly democratic work ethic that made Casa a special place, unique even among other such places on the country’s cultural map. It was that eye and that work ethic that make Casa, three decades after her death, a place that continues to function as the Revolution itself should function but often doesn’t: engaging in truly democratic decision-making and inviting new generations to take leadership, thereby insuring both continuity and change.

Throughout Haydée’s tenure at Casa, artists on the cutting edge of new ideas, genres, and imaginaries visited Cuba and lent their allegiance to the sociopolitical experiment that was taking place. Since her death, they continue to come. They write about what they see and feel. In and outside their work, they spread the word, breaking through a worn but still obstinate blockade and exposing the lies disseminated by US-based Radio Martí, sectors of the exile community in Miami, and other sources of counterrevolutionary propaganda.

And the Cuban people, through Casa, come in contact with a variety of interesting ideas, and the new poetry, novels, theater, painting, sculpture, photography, dance and music being made in other parts of the world. It is in this way that Cuban intellectuals and artists have been able to participate in the great conversations that have characterized international art and literary communities through the last half of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first. Although they live on an island, and one that has been blockaded by the United States going on six decades now, Cubans are as in touch with avant garde art and literature as citizens of Paris or Buenos Aires, Mexico City or New York, Johannesburg or Bangkok.

Much of this can be traced to Haydée’s vision. A woman of simple country origin and scant formal education, she understood art as the highest form of human expression and a necessary component of social change. Even today, so many years after her death, you can go through Casa’s doors and feel her presence. To those of us who knew her in life, it is a visceral experience. For Haydée art—all creative expression—was a form of Revolution, one that feeds, reflects, stretches, strengthens, and pushes forward the struggle for justice.

Martí’s concept of Our America—an organically unified continent—was especially important to Fidel, Haydée and others of the Centennial Generation (the generation that came of political age around the centenary of his birth). At Casa, Haydée pierced the walls separating the countries of the Americas, even those where languages other than Spanish are spoken. She also recognized the growing pockets of Latin America that exist within the United States, paying attention to work by Chicanos and Hispanics living inside “the belly of the beast,” and bringing them into the great discussions about identity, ownership and resistance taking place south of the border. In this way she also enabled them to contribute to those discussions.

Under her tutelage, Casa’s important literary contest held every year in a variety of categories branched out to include the literatures of Portuguese-speaking Brazil, Guaraní-speaking Paraguay, the French-, Dutch-, and English-speaking Antilles, the art of hundreds of indigenous cultures, Latino literature in the United States and more. She promoted writing by women. She provided space to gay artists at a time when ignorance and fear prevented them from being accepted by the Revolution’s reigning bureaucracy. Each year, when the contest judges gathered to read the hundreds of entries and award prizes in a growing number of categories, she would make a point of telling them not to worry about the political message in the texts they would read. “Remember, this is a literary contest,” she would insist.

Her methods were ingenious, creative, often surprising.

Her conversational style, privately as well as in public, also issued from her unique way of positioning herself in the world. She employed a simple lexicon even when putting forth complex ideas. She often failed to bring sentences to their expected conclusions and her recorded talks are as scattered as they are emotional. But no one ever doubted what she meant to say—because she said it perfectly.

At times she rambled, but always came back to the point she was making, her detour having pierced membranes of feeling that enriched it enormously. Her silences were as exquisite and powerful as the words she uttered. Other spokespeople for the Cuban Revolution—Fidel, Che, Raúl Roa,[19] Carlos Rafael Rodríguez,[20] and Armando Hart—gave expertly constructed lessons in history or economics. Haydée’s voice was of a different timbre. And this was not only a gender issue. There were plenty of women among the Cuban leadership or at the grassroots level whose speeches were well ordered, even powerful. Haydée’s magical thinking informed her discourse, the same magical thinking that made it possible for her to understand and embrace a myriad of creative spirits.

***

I have written about Haydée, thought about her, dreamed her presence, and pondered her dilemmas. She has come to me at unexpected moments, bringing a comforting word or revealing something about myself I thought I knew but didn’t. Because, like her, I am largely self-taught, she has made me less inhibited by my own lack of formal education. The dimensions of her sacrifice and grief put my own in perspective. She continues to push me to risk, but also to slow down and pay attention. I am constantly amazed at how advanced her thinking and action were, especially at a time when women were still considered helpmeets and servers, when precious few were able to fight their way to positions of power. Time and my own experience have also taught me to respect some of the contradictions that tore at her equilibrium.

For years I did not feel up to writing about Haydée Santamaría. Later I believed I was too old and would no longer be able to do the fieldwork required. My partner, Barbara, convinced me it was now or never. At the beginning of 2014, I proposed the idea for this book to Gisela Fosado, my editor at Duke University Press. She supported it enthusiastically. A couple of months later I was in Cuba, interviewing those who knew my subject, going through archives, and gathering material.

I wanted to visit Encrucijada and the Constancia sugar mill, now renamed Abel Santamaría, hoped to see what she saw and breathe the air she breathed. It was encouraging to find generous support from those who loved Haydée as I do. I was moved that almost everyone with whom I spoke expected me to explore the complexities as well as the heroism.

What constitutes a hero? How to evoke the condition without resorting to stereotypes or creating a one-dimensional image? Much of the complexity inherent in memorializing Haydée, as I’ve said, comes from the fact that she committed suicide. It was not a choice that was easily accepted by the PCC and others, especially in 1980. As with the Catholic Church, an institution that rejects suicide because one’s life belongs to God, Communists rejected it back then because they believed one’s life belonged to the Party. Haydée was mourned in a Havana funeral parlor, like any ordinary citizen, rather than at the Plaza of the Revolution, an honor befitting her revolutionary stature. For years after her death, her memory carried a burden of hesitancy in some quarters.

In the end, Haydée’s personal history guaranteed her respect. Still, as a woman she remained an exception to the rule. Was she a token? Outside Casa, how much authority did she really have? I often wonder what went on behind closed doors when, expected to go along with some mistaken policy or witnessing a flash of opportunism, she must have disagreed with a passion that was hers alone. Yet I’m sure her Party discipline was impeccable. Although she would not have voiced disagreement publicly, I cannot imagine her remaining silent within Party chambers.

In her best known talk about the origins of the Cuban Revolution, published in many languages, she says: “For me being a communist is not about belonging to a party; for me being a communist is to embrace a certain attitude about life.”[21] I am interested in exploring what it cost her personally and politically to walk such an uncharted line between power and powerlessness.

Haydée described the pain of Revolution by evoking childbirth:

When my son Abel was born I suffered some very difficult moments, moments like those any woman experiences when she’s about to give birth, very difficult. The pains were tremendous, they tore at my entrails, but I found the strength to keep from crying, screaming or cursing. When one has such pain it is natural to cry, to scream, to curse. So where does the strength not to do so come from? It comes from the fact that you are having a child. That’s when I realized what Moncada had been . . . we were able to resist because we knew something great was being born.[22]

She was close to her children and deeply concerned about the conditions under which all children lived. I remember how surprised I was when, on a visit to her home she rather conspiratorially led me up the stairs to her bedroom, opened the closet door, and showed me a collage of photographs. There were pictures of the children of friends and colleagues, sent to her by people she knew well and some perhaps whom she’d met only casually. Right away I spotted two small snapshots of my own Gregory, Sarah, Ximena and Ana. I had sent them to her from Mexico, just after we met. Why? Probably because I wanted this extraordinary woman to have images of those who were most important in my life. I could not have guessed she would place them, among others, on the inside of her bedroom closet door.

***

Haydée, as I say, gave birth to a son and a daughter, Abel Enrique and Celia María. He became a lawyer, she an astrophysicist and also, in the last years of her life, a member of the Fourth International. When I lived there, Trotsky was almost ignored in Cuban schools; the Revolution was beholden to the Soviet Union and its educational curriculum tended to follow that country’s version of history. But a number of Cuban Communists who were more inclined toward independent thought read Trotsky with interest.

Armando Hart[23] had the Russian revolutionary’s books on his shelf, and shared them with his daughter. Before Abel and Celia’s tragic death in an automobile accident in 2008, Celia gave a number of speeches and wrote some illuminating texts for international Trotskyist publications. Her adhesion to Trotsky’s ideology never conflicted with her love for or defense of the Cuban Revolution, or her admiration for Fidel. Her ideas in this respect, especially that of permanent Revolution, bore similarities to those evident in Ernesto “Che” Guevara’s late writing.

It would be 2005 before Hart published an article critical of Stalinism, in which he pointed out that, because the revolutionary leader had never traveled outside the Soviet Union, he lacked the broad culture possessed by Lenin and others. Among many other salient points Hart makes, he writes: “In order to promote revolutionary policy, one must understand the mobilizing importance of art and culture, understand that in these the basis of our redeeming ideas reside.”[24]

Despite its rejection by the Cuban Party, I don’t imagine her husband’s critique of Stalin seemed unusual or unsettling to Haydée. I believe she shared his views. And I also think she was less concerned with the finer points of ideological sparring than with how social change manifests itself on the ground. Furthermore, in her expansive reading her tendency was always to add rather than subtract.

I want to explore Haydée’s relationship with her children. From what I have been able to gather, from listening to Haydée and reading Celia María, she was a passionately loving mother and also expected no less from her children than the highest standards of idealism, exemplary behavior and sacrifice. Celia María has written about receiving a box of dolls one childhood birthday, being allowed to play with them for a single day, and then being instructed by her mother to pick the one she wanted to keep and give the others to children who didn’t have access to such bounty.

In this context, the way in which Haydée took her life is noteworthy. I am haunted by the knowledge that she shot herself in the home she shared with her children, both young adults at the time. Some of my interviewees told me that her son and daughter were home, others say only her son. He was the one who found her. That act, perhaps shaped by desperation and certainly removed in her mind from the impact it would have on her progeny, had to mark the latter for the remainder of their days. On the other hand, there is evidence that her suicide may have been calculated and deliberate. About her last days, Silvio Rodríguez has said: “She was saying goodbye. I got her to write a dedication in her book Haydée habla del Moncada. She wrote ‘Silvio, understand me and love me.’”[25]

Most people I interviewed felt that Haydée was out of control when she killed herself. A few believe she was absolutely sane. One saw it as a final act of free will. Celia María, in a moving elegy, wrote:

We have no choice but to respect those who decide they would rather be dead than alive. The old cliché about revolutionaries not committing suicide (she used to tell us this herself) is so foolish that just a few names are enough to refute it . . . Defarge decided he was more useful to the cause of the proletariat dead than alive . . . Who would say that Violeta didn’t give “Thanks to Life” honestly, and journey into death without fear, sure of her decision.[26]

Despite her efforts to overcome them, however, the pain Celia María endured at her mother’s suicide can be felt in a further fragment from this same text: “A single detail escapes me: I am her daughter or was, and objectively speaking she left me alive in her death, surrounded by other living dead . . .”[27] I don’t believe there is a way we, who do not choose that route, can decipher or make sense of suicide. It is always a mystery to those who remain.

In her personal life, Haydée was burdened with ghosts who never left her side: her brother Abel, her early fiancé Boris Luis Santa Coloma (who many told me was the great love of her life), and scores of other comrades who had been killed during the struggle to overthrow Batista. Year after year, every time she was called upon to speak about Moncada her first words were for those she had loved and lost. She emphasized their immortality in struggle, and reiterated that without their sacrifice the Revolution would not exist.

But those who heard her tell the story knew that each comrade’s face was indelibly seared into her memory. Rather than time healing those wounds, they remained open, raw. She could rise above them when her duties demanded, and she did. But once out of the public eye and alone again I’m sure she heard their voices, saw their faces, relived the pain of their absence.

For two decades, Haydée Santamaría and Armando Hart had what appeared to be the perfect marriage. Dedication, struggle and survival had brought them together. She often said that during the insurrectional period Armando was so bad at clandestine life she wished he would just stay in prison—where she knew he’d be safe. He was clearly the theoretician, one of the architects of the country’s 1961 literacy campaign, and responsible for a number of welcome shifts in Cuban educational and cultural policy. She was illuminated, passionate, spontaneous. Separately, each played an important role in the construction of the new society. Together they seemed an example of what a revolutionary marriage could be. Whatever else Armando Hart may have been to Haydée, he provided comfort in a long relationship that had seen many dramatic moments.

And then he left her.

Looking at a relationship from the outside, we can never know what issues unite or create divisions, what failures of one member of a couple become intolerable to the other, what may finally make life together impossible. Midlife crisis? A younger woman? Rumors abounded at the time. I preferred to ignore them then, and they seem superfluous to me now as well. Two people of such proven trajectory and unquestionable brilliance clearly also had their frailties and passions. As deeply as I loved and admired Haydée, I can imagine that living with her may not have been easy. Their separation took place shortly before Haydée took her life and may have weighed on her decision, but it never seemed to me to be the central reason for that act. I don’t believe there was a single event, but many, that compelled Haydée to choose death. It was as if she had come to the end of a journey.

Other possible “reasons” were whispered from Cuban to Cuban during the terrible days following her suicide. She had been devastated by Celia Sánchez’s death from cancer earlier that same year. Celia, another great woman of the Cuban Revolution, had been a close friend. In terms of integrity and in other important ways, they were like identical twins in an inner circle in which women were rare. And for Haydée, Celia’s death meant not only the loss of that friendship but also the disappearance of the person closest to Fidel. According to her daughter, Celia María, “Above all else, between one tear and another,” [my mother] told me, “Now we must worry about Fidel. Who will care for him like Celia did?”[28]

There had been other excruciating losses, such as Che’s death a dozen years earlier, and with it a delay in the dream of Latin American liberation they shared. An automobile accident several months before the end had almost taken Haydée’s own life, leaving her with chronic pain. Disillusionment with certain tendencies evident in the Revolution at the time may also have troubled her. And then there was the ongoing exhaustion from so much loss, what today we call Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). I will leave further speculation for later.

***

Endnotes

[1] Uruguayan poet and novelist (1920-2009).

2 Durham and London, Duke University Press, 2013.

3 Rubén Darío (1867-1916) was a great Nicaraguan modernist poet. Nineteen-sixty-seven marked what would have been his hundredth birthday. The gathering of poets and literary critics held in Cuba and hosted by Casa de las Américas was one of several held throughout the world that year.

4 In Che On My Mind there is a chapter called “Che and Haydée.” In More than Things (University of Nebraska Press, 2013), there is an essay called “Shaping My Words” that focuses on her.

5 To Change the World: My Years in Cuba.

6 Fidel Castro Ruz (1926), born into an upper-class family in Biran, Cuba, became a lawyer and eventually founded the July 26 movement with an aim to overthrowing the Batista dictatorship that had grabbed power in 1952. After six years, his movement was victorious. He served as prime minister and then president of his country until his retirement from public life in 2008.

7 Ernesto “Che” Guevara (1928) was an Argentine doctor who fought in the Cuban Revolution, went on to take several important peacetime positions in that country, and then left to wage guerilla warfare in other parts of the world. He was murdered in Bolivia in 1967.

8 Celia Sánchez (1920), Cuban revolutionary hero and Fidel Castro’s closest associate until her death from cancer in 1980.

9 José Martí (1853-1895), Cuban revolutionary, prolific thinker and writer, considered the intellectual father of Cuban liberation. He is claimed by the revolution’s detractors as well as its supporters.

10 The Cuban Orthodox Party was founded in 1947 by Eduardo Chibás in response to government corruption and lack of reform. It was nationalist in nature and pushed for economic independence. Fidel Castro was also a member early on.

11Fulgencio Batista (1901-1973) was the elected president of Cuba from 1940 to ’43, and then grabbed power in 1952. In 1959 he was overthrown by the Cuban Revolution.

12Jesús Menéndez (1911-1948).

13 Fidel Castro and his group attacked Moncada Barracks in Santiago de Cuba on July 26, 1953. They hoped to spark a popular resistance to the Batista dictatorship. The action was a military failure but political success; it initiated the revolutionary struggle that was victorious five and a half years later.

14 Cuban Women Now, 312.

15 Conversation with author, 1970s. Translation by MR.

16 Gloria Rolando (born 1953) is a Cuban documentary filmmaker whose films include “Eyes of the Rainbow (1998) about US revolutionary Assata Shakur, “Raíces de mi corazón” (2000) about the destruction of the Independents of Color political party, and many others on Afro-Cuban cultural traditions. Rolando made these remarks at a panel on her work at the Berkshire Conference on the History of Women, Toronto University, May 24, 2014.

17 Aida’s daughter Niurka Martín Santamaría, interviewed later in this book.

18 Gloria Rolando (born 1953) is a Cuban documentary filmmaker whose films include “Eyes of the Rainbow (1998) about US revolutionary Assata Shakur, “Raíces de mi corazón” (2000) about the destruction of the Independents of Color political party, and many others on Afro-Cuban cultural traditions. Rolando made these remarks at a panel on her work at the Berkshire Conference on the History of Women, Toronto University, May 24, 2014.

19 Raúl Roa García (1907–1982) was a Cuban intellectual, politician and diplomat. He served as the country’s Foreign Minister from 1959 to 1976.

20 Carlos Rafael Rodríguez (1913-1997) was a member of the PSP who served both in Batista’s and Fidel’s cabinets.

21 Haydée habla del Moncada, 37. Translation MR.

22 Haydée habla del Moncada, p 14. Translation MR.

23 Armando Hart Dávalos (born 1930), follower of Fidel Castro, married Haydée during the war. They had two children and parented many more. Hart was the revolution’s first Minister of Education, headed the 1961 literacy campaign, and later became Minister of Culture

24 “Stalin,” Hart’s article may be found on line in several places, among them: http://www.rebelion.org/noticia.php?id=10776. Translation MR.

25 Filmed by Esther Barroso Sosa. Translation MR.

26 Haydée habla del Moncada. 8. Translation MR. Ernest and Therese Defarge are fictional characters in Charles Dickens’ Tale of Two Cities. Celia Hart refers to the “Lafarges” rather than “Defarges” but in the context I believe it to be a misprint. Violeta Parra (1917) was a Chilean songwriter and singer who committed suicide in 1967. “Gracias a la vida” (Thanks to Life) is one of her most beloved songs.

27 Haydée habla del Moncada. Translation MR.

28 Haydée habla del Moncada, 4. Translation MR

This is chapter two from Margaret Randall’s Haydee Santamaria, Cuban Revolutionary: She Led by Transgression (Duke University Press, 2015).