Letter from Berlin: Syriza and the Minotaur

Berlin — The Talking Heads of Europe have spent the end of an uneasy winter trying to solve the insoluble problems of bailouts and war on the Continent.

No, I’m not talking about David Byrne’s old Talking Heads rock band of the 1980s belting out “Take Me to the River,”/ “drop me in the water.” I’m talking about those other talking heads belonging to European Union (EU) politicians, bankers, and pundits who — ever since the left-wing Syriza Party swept to a landslide electoral victory in depression-wracked Greece at the end of January 2015 — have devoted themselves to arguing about loan extensions, austerity programs, and pay-your-debts demands, even contemplating a possibly apocalyptic “Grexit” — the potential withdrawal of Greece from the Eurozone monetary system.

By the way, how monetary systems work and why they matter is one of the subjects of newly-prominent talking head Yanis Varoufakis’ book, The Global Minotaur: America, Europe and the Future of the Global Economy (2013). Varoufakis is the former Universities of Athens and Texas economics professor who ascended to the post of Greece’s finance minister as a result of the Syriza victory. His book is a popular critical history of contemporary capitalism, from the Crash of 1929 to the present, focusing on the Great Recession of 2008, all of which is of course relevant to the current EU political and economic crisis..

When they found a free moment, many of the same talking heads and various branches of the labyrinthine European Union spent some time meeting in Minsk, Belarus, with Russia’s Vladimir Putin and his Ukrainian counterpart, President Petro Poroshenko, in an attempt to arrange, at best, a shaky ceasefire in eastern Ukraine, where Russian-backed separatists (to say nothing of Russian troops and arms) have maintained control of the Ukrainian Donbas region for the last year and been primarily responsible for the deaths of more than 5,000 people. But since the latest ceasefire seemed indistinguishable from ceaseless fire, little definitive can be said yet about the prospects for cessation of armed hostilities in eastern Europe.

Finally, the talking heads and their various security forces have had to keep an eye on everyone from Islamic State-inspired terrorists to deranged loners who, in Paris, then in Copenhagen, and most recently in Tunis, have been killing (and/or threatening to kill) journalists, Jews, security personnel, and even hapless tourists, whom they regard as religious and political infidels. Most of the rest of us have been periodically appalled and, yes, terrorized, by the images appearing on our large, medium and small screens of everything from Islamic State (IS) barbaric executions to the cultural destruction of ancient Assyrian statues and other artifacts in the IS-occupied Iraqi city of Mosul.

Of all these events, the election in Greece produced something politically new in recent European politics. Naturally, a low-level, grinding war in Eastern Europe resulting in thousands of fatalities in the last year, and the Middle Eastern rise of a would-be new Islamic caliphate in the midst of civil wars in Syria and Iraq are hardly to be ignored. But the crisis in Greece represents an important turn in a crucial argument about policies that will affect not only the European Union and its monetary system, but a good portion of global economics as well.

The election of the left wing Syriza coalition represents the first ballot-box revolt against policies that have driven almost an entire EU country to the poorhouse. Although Greece was never a rich society, it nonetheless had a middle-rank economy among EU nations, and a standard of living higher than many of the former Soviet bloc countries that have subsequently joined the European ensemble. Or it did, until the crash of 2008 and the resulting “austerity” program meant to rescue Greece from impending bankruptcy. Whether the revolt will succeed is still very much up in the air. However, the decision by Europe at the end of February to avoid a further immediate Greek crisis, supposedly for at least four months, provides a chance to provisionally assess recent developments.

2.

As everyone who has been paying the slightest attention knows, the global capitalist crash that began in 2008 has left “distressed” and battered national economies wherever the tentacles of “globalization” reach. In Europe, the most distressed of these economies is found in Greece, where more than a half-dozen years after the Great Recession that began in the U.S. in 2008, the Aegean nation of 10 million people suffers from 25 per cent depression-level unemployment (over 50 per cent among young people), a GDP that has shrunk more than a quarter from pre-crash levels, and now has a third of its population living on the edge of or below officially designated poverty lines. Don’t let your eyes glaze over as you look at those numbers. That’s 25-per-cent- and-counting unemployment.

This condition of immiseration obtains despite a gigantic more-than-250-billion euro “bailout” of the Greek economy by the European Union and five years of an “austerity” program designed to correct the long-standing failings and flaws of past notoriously corrupt Greek regimes, both conservative and social democratic. The austerity program was imposed by a so-called “troika” of EU-associated institutions, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the European Central Bank (ECB) and the European Commission (EC).

Ever since 40-year-old Alexis Tsipras, head of Syriza, was sworn in as Greece’s Prime Minister on Jan. 26, 2015, “a new chapter in Greece’s uphill struggle to remain solvent — and in the eurozone — has begun in earnest ,” reported Britain’s Guardian newspaper. “After five years of austerity-fuelled recession,” as the paper put it, “that has driven the vast majority of Greeks into poverty and despair,” Syriza promised that “our immediate and most pressing priority is to alleviate the humanitarian crisis.” (Helena Smith, “Syriza forms government with rightwing Independent Greeks party,” Guardian, Jan. 26, 2015.)

From his first act, PM Tsipras, foregoing the standard suit-and-tie attire for an open-necked shirt, chose to be sworn in at a civil ceremony rather than the traditional swearing-in blessed by a high religious official. The new government continued its unconventional inauguration with a flurry of some human relief measures (including rehiring parliamentary cleaning women who had been fired and became symbols of the ravages of austerity) and blunt talk about the economy. Tsipras’s new finance minister, Varoufakis, said, “Fiscal waterboarding has turned us into a debt colony,” pointedly comparing the imposed austerity rules to the American CIA torture technique. He admitted that the prospect of new talks with EU lenders was daunting, “an extremely scary project.”

As if to confirm Syriza’s fears immediately, the same day in Brussels, the EU commissioner for economics and finance, Pierre Moscovici, said, “We all want a Greece that stays on its feet, creating jobs and growth, reducing inequality, and a Greece that repays its debts.” (Italics mine.) International Monetary Fund chief Christine Lagarde underscored the point: “There are internal Eurozone rules to be respected. We cannot make special categories for such or such country.” In short, it was to be business as usual.

Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman, a Princeton professor and columnist for the New York Times, wondered why. “To understand the political earthquake in Greece” that brought Syriza to office — the first European government “elected on an explicit promise to challenge the austerity policies that have prevailed since 2010” — Krugman suggested that it helps to look at the terms of the 2010 “standby arrangement” that brought Greece IMF and other EU loans in return for austerity and reform.

“It’s a remarkable document in the worst way,” Krugman said. The “troika,” as the dominant financial institutions are known, “was peddling an economic fantasy. And the Greek people have been paying the price for those elite delusions… the economic projections that accompanied the standby arrangements,” explained Krugman, “assumed that Greece could impose harsh austerity with little effect on growth and employment.” The projections were wrong. “What actually transpired was an economic and human nightmare,” Krugman said. Instead of the Greek recession ending by 2011, as the troika plan predicted, the situation got worse; in fact the plummeting economy didn’t hit bottom until last year, and by then Greece had “experienced a full-fledged depression.”

“What went wrong?” Krugman asked. “I fairly often encounter assertions to the effect that Greece didn’t carry through on its promises, that it failed to deliver the promised spending cuts. Nothing could be further from the truth. In reality, Greece imposed savage cuts in public service, wages of government workers and social benefits.” Despite all this, “Greek debt troubles are if anything worse than before the program started.” For one thing, the economic plunge reduced revenues. Although the government is collecting a higher share of GDP in taxes, GDP has fallen so rapidly that the tax receipts are down. As for the ballyhooed billions in bailout to cover Greek debts, it’s often forgotten that those billions of euros didn’t go to Greek citizens, they went to creditor banks, located in France, Germany, Greece, and elsewhere. The claim that “the direct job-destroying effects of spending cuts would be more than made up for by a surge in private sector optimism” proved false.

If the “supposedly hardheaded” troika officials had been truly realistic, Krugman pointed out, they “would have acknowledged that they were demanding the impossible.” Once Syriza and Tsipras won at the ballot box, Krugman advised European officials “to skip the lectures calling on him to act responsibly” and to support Syriza’s program. In fact, Krugman worried that the Syriza plan might not be “radical enough. Debt relief and an easing of austerity would reduce the economic pain, but it is doubtful whether they are sufficient to produce a strong recovery.” In calling for major changes, Tsipras “is being far more realistic than officials who want the beatings to continue until morale improves. The rest of Europe should give him a chance to end his country’s nightare,” Krugman concluded. (Paul Krugman, “Ending Greece’s Nightmare,” New York Times, Jan. 26, 2015.)

Instead of following Krugman’s sensible advice, European officials doubled down on the lectures to “act responsibly” as the Greek prime minister and his finance minister went on a tour of European capitals throughout the month of February, seeking support for an end to austerity. Although various European heads of government mumbled occasional sympathetic homilies, the main message was, Beware of Greeks bearing debts. The coldest shoulder came from German finance minister Wolfgang Schaeuble, one of the strongest supporters if not the architect of the austerity program, and the representative of the EU’s most powerful economy, and most prominent political leader, Chancellor Angela Merkel. When Greece’s Varoufakis visited Schaeuble, the reception was positively frosty.

In mid-February, as Syriza representatives continued to traipse through the EU labyrinth of institutions and offices, my favourite American economist weighed in once more, warning about a potential “Weimar” on the Aegean, and reminding Europeans of a post-World War I reparations program against Germany that contributed not a little to the rise of Hitler and Nazism.

In the present crisis, Krugman said, “You can argue that Greece brought its problems on itself, although it had a lot of help from irresponsible lenders. At this point, however, the simple fact is that Greece cannot pay in debts in full. Austerity has devastated its economy… real Greek GDP per capita fell 26 per cent from 2007 to 2013,” numbers comparable to the catastrophic World War I and after German GDP decline.

Krugman’s strongest, and least publicly appreciated point is, “Despite this catastrophe, Greece is making payments to its creditors, running a primary surplus — an excess of revenue over spending other than interest — of around 1.5 per cent of GDP. And the new Greek government is willing to keep running that surplus. What it is not willing to do is meet creditor demands that it triple the surplus, and keep running huge surpluses for years to come.” That’s because generating such surpluses would mean further slashing government spending, and “spending cuts have already driven Greece into a deep depression.” Once again, Krugman urged European creditors to “realize that flexibility — giving Greece a chance to recover — is in their own interests.” (Paul Krugman, “Weimar on the Aegean,” New York Times, Feb. 16, 2015.)

Not until the end of February did the EU and Greece come to a tentative and very ambiguous agreement to extend the rescue program through June while Greece figured out how to make further concrete reforms and the EU considered how to ease austerity strictures (but without admitting that it was doing so). In practical terms the agreement was meant to do little more than signal everybody’s good intentions. And perhaps, in reality, it was more likely intended to conceal everyone’s bad intentions.

The final stamp of approval for the extension of Greece’s bailout was given on the last Friday of February by the German Reichstag. The vote was an overwhelming 542-32, since it was backed by the Merkel-led government coalition, but the rubber stamp came amidst a great deal of grumbling, and stern assurances from Finance Minister Schaeuble that Greece would not be permitted to “blackmail” its eurozone partners. Germany’s tough stance on maintaining austerity in Greece is popular at home. German public polling shows that only a quarter of Germans backed the extension for Greece. The clamour from the right-wing tabloid press, led by the nation’s top-selling daily, Bild, was louder than the parliamentary debate. Bild’s front-page headline was a giant, war-sized font, all- caps-plus-exclamation, one-word demand that the parliament vote “NEIN!” (Stephen Brown, “Germany backs Greek extension but bailout fatigue grows,” Reuters, Feb. 27, 2015.)

The deal the Greek government reached with its creditors was widely reported as a complete “surrender” on the part of Syriza. In the widespread mixture of media cynicism, I-told-you-so’s, and satisfaction that the uppity amateurs on the Aegean were getting their comeuppance from RealPolitik, the only dissenting voice was that of the sensible Paul Krugman, who thought that “Greece came out of the negotiations pretty well.”

I probably should note that although I’m not a blood relative, friend or even acquaintance of Mr. Krugman, the reason I’m making a fuss about his views is that a) economics seems an especially difficult subject for people, even well-educated ones, to understand, and b) Krugman consistently offers clear, “evidence-based,” as we say these days, explanations of what’s going on in the murky world of finance. Krugman, a follower of the ideas of John Maynard Keynes, who believed that government-provided stimulus was the appropriate response to recession and worse, has proven correct far more often than his right-wing counterparts and their political mouthpieces in the U.S. Republican Party.

Krugman again argues that “the main issue of contention involves just one number: the size of the Greek primary surplus, the difference between government revenues and government expenditures not counting interest on the debt. The primary surplus measures the resources that Greece is actually transferring to its creditors.” He adds, “For Greece to run any surplus at all… is a remarkable achievement, the result of incredible sacrifices.” For those on the left angry “that the negotiations didn’t make room for a full reversal of austerity, a turn toward Keynesian fiscal stimulus,” well, that wasn’t the issue, at least not yet. The question at hand, in Krugman’s view, “was whether Greece would be forced to impose still more austerity.” Syriza refused to agree to aim for increased super-surpluses, and won some degree of new flexibility for the coming period. “The creditors did not pull the plug. Instead, they made financing available to carry Greece through the next few months,” Krugman noted. (Paul Krugman, “What Greece Won,” New York Times, Feb. 27, 2015.)

3.

You’d think that after all the brinksmanship, down-to-the-deadline decision-making, and general ill-tempered intransigence, that there would have been a bit of peace and quiet once the rescue package extension had been agreed. You might also think that the EU would want to reconsider austerity, not only with respect to Greece, but regarding Spain, Portugal, and other struggling EU members. Neither of those things happened.

Instead, right through the Ides of March, the solar eclipse, and the first day of spring, the talking heads ignored the signs of the season and continued performing something that seemed like a cross between a soap opera and political guerilla warfare. Each new meeting — and there were plenty of them — was billed as a make or break affair. EU leaders met in Brussels on March 19-20 for one of their periodic summits and even booked extra time for unofficial side meetings between Germany, France, Greece and sundry EU officials, including the head of the European Central Bank (ECB), Mario Draghi. The side talks ran until 2 in the morning. The German chancellor and her counterparts might as well have stayed up until morning to catch the solar eclipse and to count the crocuses.

Various forms of divining and Tarot card reading may be surer methods of figuring out what’s happening than parsing the post-talk press conferences. The verdicts ranged from glum “EU leaders in Brussels demand Greece produce economic blueprint quickly,” (that was the Guardian headline) to cheerier “live updates” suggesting momentary glimmers of hope. Donald Tusk, the former Polish prime minister who currently chairs these EU summits described the possibility “of a Greek departure from the euro as ‘idiotic,’ but also conceded that the chances of a ‘Grexident,’ or an accidental Greek exit, have risen.” Perhaps the only certain sentiment that emerged from the talks is that Belgium prime minister Charles Michel was definitely peeved about being left out of the private talks. “I’m angry,” Michel announced.

Meanwhile, History (with a capital H) was once more busy proving that if events begin as crisis, then the second (or third) time through they descend to farce. Enter the “Stinkefinger” scandal. On the weekend prior to the spring equinox, a far too popular German talk show (over 5 million viewers) hosted by Gunther Jauch, whose earnest basset-hound face deceptively conceals just another “gotcha!” journo, interviewed Yanis Varoufakis.

The seemingly benign Jauch immediately sandbagged the Greek finance minister by showing a 17-second clip from an hour-long 2013 Varoufakis lecture in Croatia (before he became a politician) in which the economist, discussing the Greek dilemma in 2010, says that Greece should have defaulted on its debts rather than accept the austerity program, and should have told the German government to deal with the fallout. In the clip, Varoufakis tells the leftist audience at the Subversive conference that Greece should have announced it was defaulting, as Argentina did, “and stick the finger to Germany and say, ‘You can now solve this problem by yourself.'” The sentence was accompanied by Varoufakis raising his middle finger.

Jauch offered himself as the representative of German outrage at being shown the “Stinkefinger” (as it’s known in German). Yaroufakis, on the distant side of a video screen, coolly replied that the tape had been “doctored” and flatly denied making the obscene gesture. The conference filmmakers in Zagreb were eventually found and said that the tape had not been altered (and that Varoufakis had indeed made the gesture), but argued that his comments had been perfectly justified, and that they’d been taken out of context and sensationalized by Jauch’s program. By the next morning, the rightwing German tabloids had reached tones of apoplectic fury more suited perhaps to publications like the Volkischer Beobachter (the chief daily of the World War II era Nazi regime). “Liar!” screamed Bild.

There matters stood until midweek, when German satirist and host of the late-night comedy show Neo Magazin Royale, Jan Boehmermann, posted a detailed confession to faking the Stinkefinger gesture, and putting it on YouTube where it had been picked up by journalists with mean intentions like Jauch. Boehmermann, a sort of low-key German version of comic Jon Stewart, showed how his crew had digitally altered the recording of Varoufakis’s talk, fabricating the finger gesture through computer generated imagery. The predictable news cycle Wunder promptly followed the satirist’s confession and left Europeans buzzing. But there was one more twist.

Some 24 hours later it became clear that Boehmermann’s confession was itself a brilliant fake. By then, Boehmermann had successfully made his point about the ridiculousness of German anger at perceived slights from Greece over the austerity argument. “Devastating Europe two times within a century,” Boehmermann neatly observed, “but going nuts when somebody’s giving us the finger. Objective debate is utterly out of the question. When a Greek gives us the finger we totally freak out, because we are Germans.” The German term for this is a semi-mangled loan word, “Ausflippen” (in English, “flipping out”). Boehmermann released a subsequent statement in which he called the accusation that his confession video was a “fake fake fake fake fake” — “absolutely false.” (Robert Mackey, “Greco-German ‘Fingergate’ Gets Curiouser and Curiouser,” New York Times, Mar. 19, 2015.)

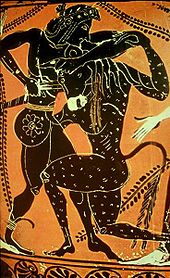

Well, after that, all that’s left is the Minotaur, the ancient Greek mythological beast with the head of a bull and body of a man, who is confined to a labyrinth in Minoan Crete, but must be pacified with regular human tribute which he periodically devours before he’s finally slain by an Athenian hero named Theseus. Yanis Varoufakis recounts the story in his Global Minotaur and uses the figure as a key metaphor in his book to get to the complicated business of what he calls “global recycling surplus mechanisms.” The original story of the Minotaur is pretty complex itself, and involves a lot of inter-species sexual shenanigans.

Whether the metaphor works for global economics is probably debatable, but it’s easy to see how the Minotaur applies to the Greek dilemma. A monster debt wrapped in a labyrinthine set of EU institutions demands relentless interest and principal payment tribute from a helpless people. Here comes a hero from Athens to try and slay the Minotaur (or maybe just to reason with it).

Mythologies aside, the one puzzle here is why the European Union can’t face up to the fact that the austerity program has been a failure, both for the economic and political health of Europe, and for its cruelly-treated direct victims, the Greek populace. There are no doubt economists and politicians (perhaps Germany’s Schaeuble is one of them) who sincerely believe that the austerity program is morally right and is beginning to take hold, and that one must stay the course. Readers of history as well as mythology will recall that even in the story of Theseus slaying the Minotaur, then getting back on board his ship and, in effect, staying the course, as he sailed home to Athens, it only led to further tragedy.