Letter from Berlin: Quo Vadis, Greece?

James Angelos, The Full Catastrophe: Travels Among the New Greek Ruins (2015).

Berlin — The Sunday evening (July 5, 2015) that Greek voters delivered a resoundingly loud “No!” — 61 per cent marked “Oxi,” Greek for “no,” on their ballots in a national referendum — against proposals to impose further economic austerity programs on their depression-battered nation, a European heat wave broke.

In Berlin, the temperature that day was 38 degrees Celsius; in other parts of the Continent — France, Italy, Switzerland — the heat had reached 40 degrees during the preceding week (hardly anything compared to the 45-50 degree deadly heat in places like Pakistan, but hot for northern and central Europe).

A couple hours before midnight, even as living room TV, computer and smartphone screens showed momentarily jubilant Greek crowds in front of the parliament building in Athens’ Syntagma Square celebrating the somewhat surprising outcome of their referendum (pollsters had predicted a too-close-to-call result), a magnificent storm broke over Berlin. There was lightning, thunder, wind whipping the courtyard trees, and a deluge of rain falling through the darkness, as people stood on their balconies in summer shorts (and less) to get a taste of the relief. It felt like an ecstatic pagan moment, Zeus unleashing a populist thunderbolt to rend the oppressive sky and let in a breath of fresh air.

It was tempting to welcome the stormy weather in Berlin as a romantic metaphor for what was happening in Athens to the south. But in real unromantic life, the weather quickly returned to the usual summer ups and downs that we discuss around the water cooler or cafe table. And in mundane political reality, precisely one week and a night shift later — prime ministers of the 19 Eurozone countries that use the euro as their common currency had gathered in Brussels, and debated the state of Greek finances all through a mid-July night — there was a shockingly harsh turnaround.

The Greek government of 40-year-old Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras and his left-wing Syriza Party was presented with, and very grudgingly accepted, an even more draconian austerity program than before in return for talks on a new fiscal bailout plan for an Aegean nation whose banks were closed and that was on the verge of complete fiscal collapse. How did Greece go from a “We’re mad as hell, and no, we’re not going to take it anymore” moment to a humiliating parliamentary acceptance of more of the same? How did a left-wing government, whose ranks include Marxist economists and populist tribunes of the people, end up imposing the latest austerity deal?

1.

In order to understand what happened in that fateful week and since, it helps to have at least an overview of the Greek economic dilemma’s latest phase, which began with the international fiscal crash and Great Recession of 2008 and beyond, as well as some sense of daily life for ordinary people in Greece in recent years — a portrait nicely supplied by journalist James Angelos in The Full Catastrophe (2015), his “travels among the new Greek ruins.”

Obviously, the Greek crisis of recent years didn’t happen overnight. Greece had been plagued over the last half-century by incompetent governments and corrosive corruption, under the aegis of both right-wing and social democratic regimes (to say nothing of military coups). But it was the United States-sparked global economic catastrophe of 2008 that spelled disaster for the Hellenic country of 10-million people in southern Europe, and revealed the full fragility of its economic structures. Although contemporary Greece was never a rich society, it nonetheless had a middle-rank economy among European Union (EU) nations, and a standard of living higher than many of the former Soviet bloc countries that have subsequently joined the European ensemble. Or it did, until the crash of 2008 and the resulting “austerity” program meant to rescue Greece from impending bankruptcy.

The capitalist crash left “distressed” and battered national economies wherever the tentacles of “globalization” reach. In Europe, the distressed economies included those of Spain, Ireland, Portugal and Italy, among others. But the most troubled of all is Greece, where more than a half-dozen years after the economic implosion, the country suffers from 25 per cent depression-level unemployment (over 50 per cent among young people), a GDP that has shrunk more than a quarter from pre-crash levels, and that now has a third of its population living on the edge of or below officially designated poverty lines, with whole families, including adult children, living on one elder family member’s pension. Don’t let your eyes glaze over as you look at those numbers. That’s 25-per-cent- and-counting unemployment.

This condition of immiseration obtains despite a gigantic more-than-250-billion euro “bailout” of the Greek economy by the European Union and five years of an “austerity” program designed to correct the long-standing failings and flaws of past notoriously corrupt Greek regimes, both conservative and social democratic. The austerity program was imposed by a so-called “troika” of EU-associated institutions, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the European Central Bank (ECB) and the European Commission (EC).

At the end of January 2015, Greek voters decided they had had enough. In national elections, they turned their backs on traditional parties like the right-of-centre New Democracy and the social democratic Pasok party, both of whom had governed since the crash. Instead, in the first ballot box revolt in post-crash Europe, the country gave a stunning victory — a near-majority of 149 out of 300 seats in the Greek parliament, and a 36 per cent plurality of the vote — to Syriza, an openly left-wing political grouping. Syriza quickly formed a majority government in coalition with the rightwing but anti-austerity Independent Greeks (Anel) minority party. The distribution of opposition seats, besides the traditional parties and a new centrist grouping charmingly named The River (To Potami), included the old Communist Party of Greece, and the openly fascist party, Golden Dawn, which received a little over 6 per cent of the vote in the fractious 7-party parliament.

“To understand the political earthquake in Greece” that brought Syriza to office, wrote Nobel Prize winning economist and New York Times columnist Paul Krugman in the immediate wake of the January election, he suggested not only that we look at the first European government “elected on an explicit promise to challenge the austerity policies that have prevailed since 2010,” but especially at the austerity deal itself. That is, the terms of the 2010 “standby arrangement” or “memorandum” that brought Greece seemingly urgent IMF and other EU loans in return for austerity and promises of reform do much to explain what happened at the ballot box.

“It’s a remarkable document in the worst way,” Krugman said. The “troika,” as the dominant financial institutions are known, “was peddling an economic fantasy. And the Greek people have been paying the price for those elite delusions… [T]he economic projections that accompanied the standby arrangements,” explained Krugman, “assumed that Greece could impose harsh austerity with little effect on growth and employment.” The projections were wrong. “What actually transpired was an economic and human nightmare,” Krugman said. Instead of the Greek recession ending by 2011, as the troika plan predicted, the situation got worse; in fact the plummeting economy didn’t hit bottom until 2014, and by then Greece had “experienced a full-fledged depression.”

“What went wrong?” Krugman asked. “I fairly often encounter assertions to the effect that Greece didn’t carry through on its promises, that it failed to deliver the promised spending cuts. Nothing could be further from the truth. In reality, Greece imposed savage cuts in public service, wages of government workers and social benefits.” Despite all this, “Greek debt troubles are if anything worse than before the program started.” For one thing, the economic plunge reduced revenues. Although the government collected a higher share of GDP in taxes, GDP fell so rapidly that the tax receipts declined. As for the ballyhooed billions in bailout to cover Greek debts, it’s often forgotten that those billions of euros didn’t go to Greek citizens through economic stimulus, they went to creditor banks, located in France, Germany, Greece, and elsewhere. The claim that “the direct job-destroying effects of spending cuts would be more than made up for by a surge in private sector optimism” proved false.

If the “supposedly hardheaded” troika officials had been truly realistic, Krugman pointed out, they “would have acknowledged that they were demanding the impossible.” Once Syriza and Tsipras won at the ballot box, Krugman advised European officials “to skip the lectures calling on [them] to act responsibly” and to support Syriza’s program. In fact, Krugman worried that the Syriza plan might not be “radical enough. Debt relief and an easing of austerity would reduce the economic pain, but it is doubtful whether they are sufficient to produce a strong recovery.” Exactly what Syriza’s program called for will turn out to be one of the issues in dispute (and we’ll return to its ambiguities in due course). Still, in calling for major changes, Tsipras “is being far more realistic than officials who want the beatings to continue until morale improves. The rest of Europe should give him a chance to end his country’s nightare,” Krugman concluded. (Paul Krugman, “Ending Greece’s Nightmare,” New York Times, Jan. 26, 2015.)

Instead of following Krugman’s sensible advice, European officials doubled down on the lectures to “act responsibly” as the Greek prime minister and his finance minister, Yanis Varoufakis, went on a tour of European capitals throughout the month of February, seeking support for an end to austerity. Although various European heads of government, particularly French president Francois Hollande, mumbled occasional sympathetic homilies, the main message was, Beware of Greeks bearing debts. The coldest shoulder came from German finance minister Wolfgang Schaeuble, one of the architects of the austerity program, who, on behalf of German chancellor Angela Merkel’s conservatuve government, demanded that Greece pay its bills, clean up its act, and impose more discipline and austerity. Other leading European economic figures, such as IMF director Christine Lagarde and Dutch finance minister Jeroen Dijsselbloem, who chairs the Eurogroup, a meeting of Eurozone finance ministers, were hardly more helpful as they dismissed the arguments of the new Greek finance minister, Varoufakis, an economics professor at the universities of Athens and Texas, and the author of The Global Minotaur: America, Europe and the Future of the Global Economy (2013).

Krugman’s strongest, and least publicly appreciated point was, “Despite this catastrophe, Greece is making payments to its creditors, running a primary surplus — an excess of revenue over spending other than interest — of around 1.5 per cent of GDP. And the new Greek government is willing to keep running that surplus. What it is not willing to do is meet creditor demands that it triple the surplus, and keep running huge surpluses for years to come.” That’s because generating such surpluses would mean further slashing government spending, and “spending cuts have already driven Greece into a deep depression.” Once again, Krugman urged European creditors to “realize that flexibility — giving Greece a chance to recover — is in their own interests.” (Paul Krugman, “Weimar on the Aegean,” New York Times, Feb. 16, 2015.)

Not until the end of February did the EU and Greece come to a tentative and very ambiguous agreement to extend the rescue program through June while Greece figured out how to make further concrete reforms and the EU considered how to ease austerity strictures (but without admitting that it was doing so). In practical terms the agreement was meant to do little more than signal everybody’s good intentions. And perhaps, in reality, it was more likely intended to conceal everyone’s bad intentions.

2.

The four-month period from the February extension of the rescue program to the July referendum was marked by an air of continual crisis, countless “final deadline” late-night meetings that never produced finality, and an emerging hardline EU position, led by Germany’s Schaeuble, that insisted that only a program of more austerity was on offer if the Greeks wanted additional fiscal relief. The inconclusive negotiations, the spectre of recurrent deadlines (usually having to do with Greek repayment due dates), and the bland intransigence of the creditors made the actual economic situation in Greece that much worse. More small businesses closed as worried customers hedged on purchases; tax receipts declined, reducing the government’s ability to manoeuvre; direct suffering increased (in terms of access to food, electricity and other daily necessities); eventually banks closed, while imposed capital controls restricted daily ATM withdrawals to 60 euros. Finally, the unrelieved uncertainty was stressful and demoralising to the populace.

What went on in the closed-door negotiations is a matter of interpretation and speculation. The contempt of the European institutions for the “inexperience,” “amateurishness,” and “naivete” of the new Greek government oozed out at every opportunity. The most maligned person of all was Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis, a telegenic, outspoken, rather unusual political figure who enraged other Eurozone finance ministers. Even Varoufakis’s sartorial style — the absence of standard buttoned-up suits and ties in favour of informal open shirts, which the Syriza government had adapted from the day of its swearing in — marked him off from his more conventionally attired fellow ministers. He was accused of “flamboyance,” “lecturing” his colleagues, and a tendency to stick the finger to people who thought they were owed subservience in addition to debt repayment.

But in an after-the-fact interview, Varoufakis described with astonishment how his presentations were received during the months of meetings. “It’s not that [they] didn’t go down well,” Varoufakis recalled, “it’s that there was point blank refusal to engage in economic arguments. Point blank. … You put forward an argument that you’ve really worked on – to make sure it’s logically coherent – and you’re just faced with blank stares. It is as if you haven’t spoken… You might as well have sung the Swedish national anthem – you’d have got the same reply. And that’s startling, for somebody who’s used to academic debate. … The other side always engages. Well, there was no engagement at all. It was not even annoyance, it was as if one had not spoken.” While EU officials regarded such frankness, whether in or out of formal sessions, as not playing by the rules, more sympathetic observers (including me) heard the ring of truth in Varoufakis’s comments. Similarly, rather than seeing the admittedly inexperienced Greek representatives as mere amateurs, those same observers were struck by the composure, retention of dignity, and refusal to panic consistently displayed by Tsipras and his team. (Interview with Yanis Varoufakis, New Statesman, July 13, 2015.)

In the end — or perhaps we should say in the middle of the muddle — Tsipras and Syriza made a surprise move. Faced in late June with the latest unbudging EU proposal for an agreement, Tsipras announced that the deal would be put to the Greek people in a referendum for a yes or no vote. Observers were quick to note, with irony intended, that in the land of the mythic birth of democracy, the government had decided to try something new — namely, democracy.

The Eurozone representatives were infuriated by the Syriza decision, and many of the comments of EU officials could be read as an open call for “regime change.” Within Greece, the mainstream opposition parties and press quickly lined up for a “yes” side campaign, while Tsipras led the call for a rejection of the most recent austerity proposal, and finance minister Varoufakis vowed to resign in the event of a yes vote. There was a heated week-long run-up to the vote, featuring rival street demos, a deluge of competing TV and newspaper op-eds, and the sense that at the very least this was a moment of Greeks deciding something for themselves rather than being subject to bullying outside ultimatums.

On the night of July 5, as we know, the storm broke and Greek voters, especially young people and workers (according to post-referendum surveys) decisively voted “No” by a 61 per cent majority. What we don’t really know is what the voters intended by saying no, and what the leftist government understood the vote to mean.

The ambiguity goes back to Syriza’s stunning election victory earlier in the year. Again, there are questions about the mandate the leftist government was given. Some of that ambiguity is understandable, given that Syriza is not a centralised party but a disparate coalition of leftist groups, includng a “Left Platform” caucus that includes such prominent economists and political theorists as then energy minister Panagiotas Lafazanis; Stathis Kouvelakis, a member of Syriza’s central committee; and Costas Lapavitsas, author of The Eurozone in Crisis (2012) and, with German economist Heiner Flassbeck, Against the Troika: Crisis and Austerity in the Eurozone (2015).

We know that Syriza’s “Thessaloniki Programme” of late 2014 called for massive debt write-offs, and remaining repayments to be based on future economic growth, as well as significant easing or reversal of the austerity measures and a major public investment/stimulus program. All of this was envisaged as occurring through “hard” negotiations with the EU institutions, and assumed that Greece would firmly remain within the Eurozone monetary union.

Those on the left-wing of the Syriza coalition thought the plan was utterly unlikely and thinkers like Lapavitsas canvassed options for Greece’s exit (or “Grexit”) from the euro. By now, there was considerable economic agreement extending beyond hard-left Syriza members that Greece’s initial membership in the Eurozone (dating back to 2001) had been a mistake, and something of a fraud, in that the books disclosing Greece’s economic situation had been falsified by the government of the day (with help from the American investment banking firm, Goldman Sachs). The Left Platform group also challenged what they regarded as a romanticized view of the “European project” and questioned whether an EU dominated by the conservative economic policies of “neoliberalism” was an entity worth preserving. (Tariq Ali, “Diary,” London Review of Books, July 30, 2015 for the Thessaloniki document; and Costas Lapavitsas, “To beat austerity, Greece must break free from the euro,” The Guardian, March 2, 2015.)

Once in office, the new Greek government quickly learned that most of Europe was in no mood to compromise or to admit that austerity had been a failure, and the resulting negotiations turned into a kind of “mental waterboarding” (I think the colourful phrase is from Varoufakis). Tsipras may have seen his mandate as simply resisting austerity, a commitment to seek debt relief, and a determination to stay within the Eurozone. If that proved impossible (as it did), his fallback position was to get the best deal he could manage, even a bad one, while retaining the euro currency. At no point, apparently, was there serious contemplation of a “Grexit” by the Syriza mainstream. In the event, the negotiations proved more a trap than anything else and it’s possible that calling the referendum was a final bid to resist EU austerity and secure a better negotiating position by a powerful demonstration of popular will. (There have been rumours that Tsipras was disingenuously expecting a “Yes” vote rather than the “No” he campaigned for, and that such an outcome would authorize him to accept the EU imposed parameters, but I’ve been unable to locate any hard evidence supporting those claims.) (Leftwing analysis of the situation can be found, e.g., at Sebastian Budgen and Stathis Kouvelakis, “Greece: The Struggle Continues,” Jacobin, July 14, 2015, and Slavoj Zizek, “Greece: The Courage of Hopelessness,” New Statesman, July 21, 2015.)

What referendum voters intended was clearer at the macro level, but less certain in practical terms. What many Greeks wanted was to simply utter a giant, unequivocal “No!” to the European powers-that-be, both as an expression of the popular will against austerity and as a form of catharsis in the face of much disrespectful stereotyping (and “scariotyping”) of the Greek populace as “lazy,” “feckless,” and lolling about in undeserved early retirement on their jewel-like Aegean islands.

What was far less clear was, Did the public No also mean a willingness to exit the euro, re-establish a drachma currency that could be attractively devalued, and to sail upon the uncharted waters of debt default and an unprecedented withdrawal from one of Europe’s central institutions? The evidence we have from subsequent events suggests that a plurality of referendum voters were saying No to more austerity, but Yes to continued membership in the Eurozone. The desire may have been contradictory, but there’s no requirement of referendum voters that their desires be coherent. Syriza leftists tended to view the powerful No result as a surge of class and generational consciousness that could have permitted the government to embark upon a truly radical program of bank and other nationalizations, popular self-help economic programs, and something approaching the look of genuine socialist aspirations.

The latter ambitions were quickly quashed. The first thing that happened on the morning after the referendum and its late-night celebrations was the announcement by Yanis Varoufakis that he was resigning as finance minister despite the referendum no vote. In a blog post, he wrote, “Soon after the announcement of the referendum results, I was made aware of a certain preference by some Eurogroup participants, and assorted ‘partners,’ for my… ‘absence’ from its meetings; an idea that the prime minister judged to be potentially helpful to him in reaching an agreement. For this reason I am leaving the Ministry of Finance today. I consider it my duty to help Alexis Tsipras exploit, as he sees fit, the capital that the Greek people granted us through yesterday’s referendum. And I shall wear the creditors’ loathing with pride.” With that, the ever-stylish Varoufakis, in t-shirt and leather jacket, rode off on his motorcycle in the direction of the Parthenon, or wherever former Greek finance ministers head off to when their duties are finished. Varoufakis was promptly succeeded by Euclid Tsakalotos, a softer-spoken, Oxford educated scholar, who was already leading the talks with Greece’s creditors. (Yanis Varoufakis, “Minister No More!”, yanisvaroufakis.eu/, July 6, 2015.)

If anyone thought that the No referendum and Varoufakis’ resignation would mollify the Eurozone ministers — and there were several pundits who did — they were mistaken. Tsipras was apparently not one of those who saw a rosy dawn the morning after. In the week that followed, not only were the remnants of any conceivable socialist dream vaporized, but the reality of renewed austerity thudded down amid the closed bank doors, threatened foreclosures, and restricted cash machines.

Still, many observers were retrospectively surprised that Syriza apparently didn’t have a Plan B, in case Greek creditors didn’t relent. As economist Paul Krugman told a CNN interviewer (on July 20), “It didn’t even occur to me that they would be prepared to make a stand without having done any contingency planning… Amazingly, they thought they could simply demand better terms without having any backup plan,” namely, a Grexit strategy.

Krugman was right to be astonished by the seeming absence of contingency planning. In fact, there was a Plan B, as former finance minister Varoufakis revealed a few days after Krugman’s remarks. It began even prior to Syriza’s election. Varoufakis, at Tsipras’s request, convened a small team of advisors, to work on the practicalities of a “Grexit,” if it should prove necessary, and the plan eventually became quite elaborate as the Grexit group tried to figure out how to convert from the euro without plunging the country into chaos. When Varoufakis admitted that there had indeed been a contingency plan, this produced a brief brouhaha in the Greek conservative press and some opposition party calls in parliament for an investigation. The word “treason” was breathed by some of Syriza’s political opponents, but the story was of relatively minor importance. As Varoufakis put it, the country would have “been remiss had it made no attempt to draw up a contingency plan.” (“Greece rocked by reports of secret plan to raid banks for drachma return,” The Guardian, July 26, 2015; Jack Ewing and Niki Kitsantonis, “Greece Made Preparations to Exit Euro,” The New York Times, July 27, 2015.)

More interesting was the question of why the alternative plan wasn’t implemented — and why Tsipras didn’t take the possibility of Grexit more seriously.Instead, Tsipras immediately proposed to the EU authorities a deal that appeared to accept most of the strictures that the Euro ministers had insisted on for months, and even brought in a team of French technocrats to polish the language of the capitulation. While insiders and mere observers argued over whether Tsipras’ actions constituted a complete U-turn, “betrayal,” or pragmatism in the face of hopelessness, the down-to-the-deadline negotiations continued in Brussels.

Only after an all-night meeting of Eurozone prime ministers that ended on Monday, July 13, was an agreement reached: an agreement to negotiate a further agreement for a third bailout package for Greece, amounting to somewhere in the range of 90 billion euros, to be conducted over the next several weeks. To secure even this much, Greece was required to accede to an extensive set of pre-conditions that included immediate pension and tax increase reforms, as well as the establishment of a large privatization fund that would oversee the sell-off of Greek publicly-owned assets. Even as this incursion into Greek sovereignty was imposed, the justification of the harsh measures was captured by the insulting question that had been openly asked at the negotiations, “Can we trust the Greeks?”

A few vague sentiments were uttered about “debt relief,” but nothing was put on paper, despite an IMF report that appeared in the midst of the negotiating frenzy declaring that any deal that failed to include substantial debt write-downs would be unworkable. The IMF report, confirming what Greek officials had been saying for months, was seen as a move by the U.S., which has significant influence within the international fund, to signal the Obama administration’s support for a less onerous bailout package. In any case, what to do about the unpayable debt was left to future considerations. One other report that surfaced during the final hectic moments was from the German finance ministry, and was apparently backed by Schaeuble. It floated the notion that Greece take a “temporary exit” from the Eurozone, even though Eurozone rules, which Schaeuble had so assiduously defended, makes no provision for such an innovation. This was perhaps the one moment when the views of the conservative German finance minister and the socialist wing of the Greek government temporarily and somewhat bizarrely coincided. The official Greek delegation to the negotiations, however, was committed to staying in the Eurozone.

The Greek parliament was given 72 hours to approve the deal. Tsipras and his new finance minister returned to Athens and told the parliament that they personally thought it was a “bad deal” that wouldn’t work, but nevertheless urged the legislative body to support it for lack of any practical alternative. Some 40 MPs from Syriza’s 149-member contingent, including former finance minister Varoufakis, cast another No vote, but Tsipras had an easy majority consisting of the bulk of his Syriza colleagues, as well as Yes votes from the mainstream opposition parties. A week later, the parliament was required to pass a second package of pre-condition legislation and again did so after another long, hot night of political rhetoric as normal summer temperatures in Athens pushed 40 degrees. This time, not even thunderstorms would provide either metaphors or relief.

3.

In the days after the deal was sealed there was a bit of blowback directed at the over-bearing Germans, both from inside and outside Germany.

On late-night German TV, two young comedians performed a skit in which two German businessmen on holiday discuss the Greek situation on their smartphones from their respective luxury hotel rooms, with dialogue consisting only of headlines that had appeared in the German press: “Sell your islands, you broke Greeks, and the Acropolis as well!”, “Nein! No more billions for the greedy Greeks. Nein! nein! nein!”, and “We have debts too, but we can repay them because we get up early in the morning and work all day!” The send-up of self-righteous Germans belittling the uppity Greeks was framed by film title cards that said, “This summer we Germans have an historic opportunity — ” followed by, “The opportunity not to behave like assholes for once.” In the midst of so much ponderous political seriousness, it was reassuring to know that at least some people in Germany had a pretension-puncturing sense of humour.

In the sober light of day, the assessment by Germany’s most prominent intellectual, 86-year-old Jurgen Habermas, was equally damning. The famed Frankfurt School philosopher judged the outcome “damaging.” “ill-advised,” and unlikely to work. The “toxic mixture of necessary structural reforms… with further neoliberal impositions,” said Habermas, “will completely discourage an exhausted Greek population and kill any impetus to growth.” Worse, the package was an admission by the European Council of political bankruptcy: “the de facto relegation of a member state to the status of a protectorate openly contradicts the democratic principles of the European Union.”

In terms of Germany itself, Habermas said, “The German government made for the first time a manifest claim for German hegemony in Europe — this, at any rate, is how things are perceived in the rest of Europe… I fear that the German government, including its social democratic faction, have gambled away in one night all the political capital that a better Germany had accumulated in half a century — and by ‘better’ I mean a Germany characterised by greater political sensitivity and a post-national mentality.”

Even harsher critics of what they saw as German bullying of Greece heard echoes of poet Paul Celan’s Holocaust poem, “Deathfugue,” and its famous couplet, “death is a master from Germany his eyes are blue / he strikes you with leaden bullets his aim is true.”

In the wake of the new austerity deal, it was reasonable to ask what the Tsipras government, now riven by its own dissenters, could realistically hope for. In the meantime, the Eurocrat clerks busily attended to the niceties — drawing up requisite legislation for the Greek parliament to rubber stamp, getting the European Central Bank to pump some liquidity into the Greek financial sector so that banks could re-open, and crafting a longer-term plan that many thought was unworkable. Paul Krugman, noting “a bit of a lull in the news from Europe,” said the “underlying situation is as terrible as ever.” He called the scheme for more austerity, limited if any debt relief, and the retention of the euro, especially the latter, “Europe’s impossible dream.”

At most, the Tsipras regime, supported by the old opposition parties (since their programs are now not substantially different from that of Syriza), and still enjoying a good measure of popular support, on the grounds that, “Well, Tsipras tried his best, but there was no alternative,” perhaps sees a few glimmers of twilight in the general hopelessness. It might hope that the unworkability of the new imposed deal will become apparent and lead to modifications, that the bad publicity of German bullying and the increased ideological tensions between Germany, France, and Italy will have a longer-term beneficial effect, and that the IMF admission that there needs to be enormous “debt relief” (which Syriza argued for all along) will lead to a substantially different package in the end, one that’s closer to the Keynesian call for economic stimulus made by internationally known economists like Krugman and such colleagues as Joseph Stiglitz and Thomas Piketty.

Beyond the immediate Greek situation, there has been a considerable amount of reflection on the frayed dream of a unified Europe. This isn’t the place to canvass the lot of it or to argue over more cogent leftist doubts about the viability of the project. The best of these necessarily inconclusive speculations, to my mind, is Irish Times literary editor Fintan O’Toole’s essay, that appeared at the time of the Greek referendum. Recalling his youth in Dublin in the 1970s when the notion of being “into Europe” generated earnest enthusiasm, he asks, “But what did ‘Europe mean?”

“It was not a physical place,” muses O’Toole. “Ireland had, after all, always been part of Europe. And the European Economic Community was not, in any case, Europe — it was a small fraction of the continent. But it wasn’t a mere set of trading and institutional arrangements either. It was a story, an imaginative fiction… [and] the capacity to believe in fictional constructs is a defining element of what makes us human, because without it we cannot co-operate with people we do not know.”

“The question now,” O’Toole wonders aloud, “is whether it still exists at all, whether ‘Europe’ has lost its hold on our collective imagination. All the evidence suggests that it has.” Well, perhaps not all the evidence, but a good portion of it. O’Toole cites the European failure to deal with the current flood of refugees and migrants, the seemingly failed Greek appeal to “our shared European values,” the erosion of democracy, open borders and the welfare state, and even solidarity. “Who now believes that the average person in Frankfurt or Helsinki sees the pensioner rummaging in a bin in Thessaloniki as a fellow citizen?” he asks, adding, “The stories Europeans are telling themselves about what’s going on around them are not just different but mutually exclusive and mutually antagonistic.”

There’s always a story, O’Toole concedes, but the current one “has a wildly improbable plot in which years of austerity magically produce economic growth, mountains of public debt are paid off by shrinking economies… and everyone lives happily ever after… There’s certainly a lot of imagination in this story. But its ability to sustain a collective enterprise among 28 stubbornly individual nations is negligible.”

About the only people who retain a belief in the old story of Europe are “on rickety boats in the Mediterranean, trying to make their way to an imagined continent of compassion, solidarity and security,” O’Toole says, referring to the wave of refugees and migrants. “If they ever get to shore, they will find at best a grudging welcome. But those who purport to share their belief in what Europe means badly need some of their desperate optimism,” he concludes. (Fintan O’Toole, “Has Europe lost its hold on our collective imagination?”, The Guardian, July 5, 2015.)

4.

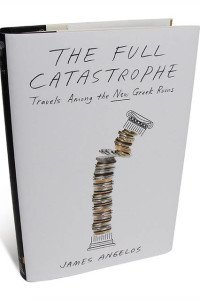

For those who have had enough of the politics of the Greek crisis, and its media counterpart — “All Greek crisis! All the time!” — but who are nonetheless interested in Greece and, like Paul Krugman, have noted the “bit of a lull in the news,” this may be the moment to recommend James Angelos’ The Full Catastrophe: Travels Among the New Greek Ruins. (The title comes from a line in the popular 1964 film, Zorba the Greek, based on the Nikos Kazantzakis novel, but Angelos avoids much of the kitsch and sentimentality of the hit movie.)

Angelos is a Greek-speaking American journalist of Greek descent, and his book, finished just as Syriza was coming to office in January 2015 and published this summer, has the big advantage of actually introducing us to the ordinary people and the extraordinary landscapes of Greece. For those who want to go beyond the 15-second “streeter” interviews and the “sound bite” opinions featured on television, Angelos offers a more satisfying alternative and a story far more accessible than those worthy, informative, but hard to penetrate books about the economic contradictions of the EU and Greece.

He begins on the island of Zakynthos, off the coast of the Peloponnese peninsula, where in the harbor town square there’s a statue of one of the poet-heroes active in the nineteenth century independence struggle of Greece. Angelos is here because, a few months before, at a dinner party in Berlin, he had learned about the “Island of the Blind.” It’s a place where “Greek words such as fakelaki (‘small envelopes’), the Greek slang for a bribe handed over in order to, as Greeks often put it, ‘oil’ the government machinery” are familiar. On Zakynthos, Angelos had heard, there was “a ridiculously high number of Greeks… claiming to be blind in order to collect a government disability check.” Nearly 2 per cent of the population of 39,000 — about nine times the rate of sightlessness in most of Europe — was discovered to be receiving benefit payments for blindness. Angelos tracks the scheme from the local hospital where its sole ophthalmologist diagnoses the alleged disability, to the city hall officials who sign off on the claims, to the back country residents who pocket the benefits (minus the various fakelaki, of course).

In an overview introduction, Angelos offers a broad caution. When the eventual inspectors examined the Greek social fabric, they “found big problems almost everywhere they looked. A deeply entrenched tradition of political patronage meant politicians handed out social benefits to select groups in exchange for votes, while often leaving the most vulnerable to fend for themselves. Tax evasion was pervasive and Greek tax collectors frequently cooperated with tax evaders. Public workers were hired often not because of their qualifications, but because an aunt or a cousin knew a mayor or parliamentarian.” The litany was long.

Angelos, who’s written for the Wall Street Journal and as a freelancer, worked and traveled in Greece during most of the period of economic catastrophe. Among his virtues is that he doesn’t appear to have an ideological axe to grind as he visits off-the-main-road communities, investigating various stories, and yet, at the same time, he doesn’t sugarcoat the tales of everyday corruption that permeate the sinews of Greek society.

There’s a temptation to see Angelos’ portrait as a confirmatory documentation of a dysfunctional society, or to sensationalize the incidents of fraud and crime he recounts (as some jubilant conservative critics have done), but I think a more appropriate perspective is to see that his first-hand account of Greek life helps us understand the difficulties that any political regime faces when attempting to remedy long-standing failings. Rather than sensationalizing Greece’s failings, Angelos manages to humanize its corruption, if that phrase isn’t an oxymoron. His basic sympathies urge him to “report a story about how [the] scandals attract a great deal of attention, but say little about the average, honest Greek.” When the facts fail to lend support to such ideas, he reports that, too.

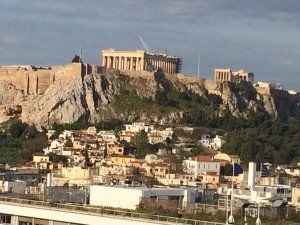

Angelos covers a lot of sun-drenched territory and azure-blue waters. On the island of Hydra, he gets to the fine points of tax evasion in a seaside taverna. When the government of the day attempts to demonstrate its sincerity in shrinking the civil service by firing the entire cast at the public broadcasting corporation, Angelos reports on the broadcasters’ sit-in. He profiles a nonagenarian national hero, Manolis Glezos, a supporter of Syriza, who became famous as a teenager during World War II for climbing atop the Acropolis and taking down the occupying Nazi flag, then successfully escaping. As he often does, Angelos strikes just the right nuanced tone about his subject, at once venerated hero and shrewd demagogue.

Perhaps the most rending tale in the book is Angelos’ journey to Greece’s northeastern border with Turkey, where refugees from throughout the region attempt to ford the dangerous local river. Many of them don’t make it; Angelos eventually visits the Muslim graveyard of a nearby village where their bodies are interred. Back in Athens, Angelos devotes another harrowing chapter to the story of a neighbourhood hostile to Afghan immigrants who have turned up there, and how the openly fascist Golden Dawn organization exploits the residents’ anger.

Angelos’ passage “among the new Greek ruins” is another instance where a thousand (or more) words is worth more than a single misleading picture on one of our sundry screens. The Full Castrophe is a modest, but engaging journalist’s take; it has few pretensions to political or philosophical depth, but one comes away from its pages with a slightly better feel for the Greek reality. That’s a pretty good accomplishment in a situation where the question, Whither Greece?, couldn’t even be answered by the Delphic oracle.

Berlin, July 24, 2015