Letter from Europe: Worst-Case Scenarios

William Drozdiak, Fractured Continent: Europe’s Crises and the Fate of the West (2017).

At 3 a.m. one fateful middle-of-the-night in November 1989, William Drozdiak, then foreign editor of the Washington Post, was awakened by the phone in his hotel room in Bangkok, Thailand. At the other end of the line, the familiar raspy voice of Drozdiak’s boss, Post executive editor Ben Bradlee, said, “They’re tearing down the Wall. Get your ass to Berlin!”

Fall of the Berlin Wall, 1989.

Now, more than a quarter-century after the fall of the Berlin Wall — that forbidding emblem of the Cold War — Drozdiak is again making the European Grand Tour. Fractured Continent is his somber report on the state of the union: the European Union (EU), that is.

The argument about the fragmentation of Europe became a little more timely than it already was when talks to form a coalition government in Germany broke down at the end of last year, just as Drozdiak’s book was arriving in bookstores. The negotiations followed an inconclusive election last September that saw long-serving Chancellor Angela Merkel, head of the governing Christian Democratic Union party (CDU), win a fourth term in office – but with a substantially reduced plurality that did not easily lead to the formation of a new coalition government.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel.

Indeed, it was not until well into the new year that talks hesitantly picked up again when Merkel met with her chief rival and former coalition partner since 2013, the left-of-center Social Democratic Party (SPD), which had initially announced that it would prefer to sit in opposition rather than be part of another “grand coalition” – the last one had resulted in its lowest election totals in decades. An agreement wasn’t cobbled together until February 2018 and still awaits a mail-ballot ratification vote (due the first week of March) from the SPD’s 450,000 members. Since Germany is seen as the linchpin of Europe these days, Drozdiak’s notion of a “fractured continent” has increasing resonance. And not just in Germany.

Just a side-note here on proportional representation systems versus first-past-the-post (FPP) electoral arrangements, which has lately become a topic of debate in North America, particularly in Canada. Most of Europe uses proportional representation schemes – which are often fairly complicated – and while they succeed in broadening the number of voices heard in parliamentary debates, it’s useful to remember that they’re not a panacea.

While no doubt preferable to FPP systems that regularly produce disproportionate majorities for parties with mere pluralities, proportional representation can also lead to paralysis in forming governing coalitions – and coalitions are almost a necessity since single parties rarely achieve a majority. Especially in recent years, as mainstream parties have been shredded by populism and multiple small parties, proportional representation can produce considerable fragmention. (The 2017 German election saw the following results: CDU, 33 per cent (down from 41 per cent); Social Democrats, 20 per cent (down from 26 per cent); Alternative for Germany (AFD) 13 per cent; Free Democrats (FDP), 11 per cent; Left Party, 9 per cent; Green Party, 9 per cent.)

Drozdiak begins his journey with a stop at a literary landmark that many European and other commentators have nodded to in the last couple of years. It’s an almost one hundred-year-old poem that worries that “Things fall apart; the center cannot hold; / Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world…” and laments that “The best lack all conviction, while the worst / Are full of passionate intensity.”

Those lines from W.B. Yeats’ poem “The Second Coming” (1919), were quoted more often in the annus horribilis of 2016 than in any of the preceding thirty years, according to the data firm Factiva. As a headline in the Wall Street Journal put it, “Terror, Brexit and U.S. Election Have Made 2016 the Year of Yeats.” (WSJ, Aug. 23, 2016). Yeats’ poem appears as the epigraph to Fractured Continent, and the answer to the question of whether the center can hold (or even if it should), which the poem raises, remains open. It’s one of the major questions of the present “conjuncture” for Drozdiak and other commentators.

(Small disclosure: in early 2017, a few months before Fractured Continent appeared, I published a politically similar book, Letter from Berlin: Essays 2015-2016 (Dooney’s, 2017), in which I also cited Yeats’ pertinent lines and pondered the events of that previous horrible year, suggesting, I suppose, that Drozdiak’s anxieties are not idiosyncratic, but widely shared.)

Among the anxieties that Drozdiak quickly reprises: “a surge of refugees from Syria’s civil war threatened to overwhelm the continent”; terrorist attacks by ISIS-inspired supporters struck an array of European capitals, including Paris, Brussels, London and Berlin; Russia’s pursuit of aggressive actions ranged from the Middle East to Ukraine, plus cyber-meddling; a multi-year economic recession for much of Europe; and finally the double-whammy of the “Brexit referendum” that will see Britain quit the EU, and the election of the populist demogogue, Donald Trump, as the U.S.’s 45th president.

France’s Marine Le Pen (l.), Holland’s Geert Wilders (r.).

The prospects for 2017 that Drozdiak surveyed didn’t look promising. He worried about “voters in the Netherlands braced for the possibility that Geert Wilders, the leader of the xenophobic far-rght Freedom Party might become the country’s next prime minister.” Similar spectres haunted Italy, and in France, Marine Le Pen, head of the right-wing National Front and one of the continent’s most prominent populist nationalists, was an increasingly plausible candidate in the spring 2017 presidential election. To make matters more perilous, EU members Poland, Hungary, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic – known as the Visegrad countries – were speeding along a road to perdition that some of them called, with approval, “illiberal democacy.” Similarly, Austrian voters were entrenching right wing parties in government. And finally, financially stressed EU members on the geographic peripheries, such as Greece, Portugal and countries in the Balkans, continued to sag under imposed “austerity” measures.

As Drozdiak sums it up: “Just a quarter century after the liberal international order of open markets, free speech, and democratic elections had triumphed over the forces of communism, the Western democracies now seem in danger of collapsing, as a backlash against globalization arouses angry opponents of immigration, free trade, and cultural tolerance.” Drozdiak hears echoes of nascent 1930s fascism, as economic flows of trade and investment weaken, political demagoguery grows, and income inequality divides become sharper, so that democracies “are becoming susceptible to xenophobic and autocratic tendencies by leaders who are tempted to play the nationalist card.”

Certainly, the “end of history” euphoria that Drozdiak had witnessed in Berlin in 1989 was overblown. Nonetheless, in the following decades, the EU “embarked on a phase of expansion to embrace the new democracies in Central and Eastern Europe” that saw the organization grow to 28 countries. The Maastricht Treaty of 1992 culminated in a single European currency, the euro, and the Schengen Agreement three years later abolished many borders for citizens and travelers.

In the last decade, however, most of the EU’s accomplishments in terms of integration toward a united, prosperous and peaceful Europe have become imperilled, and the post-Berlin Wall quarter-century is more often experienced today as a deep political disappointment and bafflement. It’s a tone of voice I hear more frequently among European friends in Berlin. The disappointment is directly proportional to the utopian ambitions of “leaving behind centuries of nationalism, bloodshed, and destruction…” in favour of a “United States of Europe.”

The Reichstag at night. Berlin.

Drozdiak’s itinerary, appropriately enough, begins in Berlin, “the new epicenter of power.” The story starts in the vicinity of the renovated 19th century Reichstag building, topped by architect Norman Foster’s postmodern glass dome, a Berlin tourist landmark that provides views both of the city beyond, and into the parliamentary Bundestag chambers below – the see-through view meant to represent post-Wall political transparency. Each of Drozdiak’s chapters, like the Berlin one, presents a portrait of an EU capital, and beyond. The Berlin story is followed by reports from London, Paris, Brussels, Warsaw, Athens, and elsewhere, as well as more distant points, including Moscow, Ankara, and Washington.

Drozdiak starts with one morning in September 2015, when Angela Merkel – the political figure as much at the center of the current European narrative as anyone else – woke to an unfolding human catastrophe. The train station in Budapest, Hungary was overwhelmed by thousands of Syrian civil war refugees trying to move north. Hungarian authorities refused to let them continue their journey unless other countries declared that their frontiers would remain open and that the refugees would be welcome (and that Hungary would not be stuck with the unwanted guests).

That was the moment that Merkel made a remarkable and unexpected decision that would become a central theme, with significant repercussions, in the political arguments of present-day Europe. She declared Germany’s borders open. Before the refugee program was eventually slowed from a flood to a trickle, Germany took in close to a million people – war refugees from Syria, but also thousands of others from Iraq, Afghanistan, and many beleaguered African nations, equally afflicted by violence and economic deprivation. (This was not the first time Germany opened its borders: it had done something similar during the Yugoslavian war of the 1990s, admitting more Bosnian refugees than any other state in Europe.)

It was an uncharacteristic decision on Merkel’s part, and not undertaken without misgivings. As Drozdiak says, “She is renowned for her habit of playing for time, postponing critical decisions until she has carefully reviewed all potential consequences.” Drozdiak notes that Germans have even transformed her name into a verb – “to merkel” – meaning something like muddling through. “But on this occasion,” Drozdiak writes, “Merkel decided to move boldly, even recklessly, to defuse what she viewed as a moral and humanitarian crisis that threatened to overwhelm Europe.”

The image of a drowned refugee child seen around the world.

Merkel’s invocation of a “welcome-culture” and open borders had been building up through the year, featuring for her both heart-rending scenes (the image of the body of a drowned 3-year-old refugee we had all seen on our televisions) and moments of revilement, as when Merkel turned up in one former East German town and was openly cursed by residents resentful at the prospect of hordes of foreigners. To make matters worse, Merkel had barely consulted with blatently reluctant EU partners, loathe to take on the humanitarian crisis. I remember that in early 2016, Berlin civil servants were scrambling to rent additional office space simply to process the paperwork involved in accomodating masses of refugees. (A fictional portrait of the chaotic refugee situation can be found in Jenny Erpenbeck’s novel, Go, Went, Gone (2015; tr. 2017).)

Hungary Prime Minister Viktor Orban.

At EU headquarters in Brussels, Merkel was the recipient of a sharp lecture from Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban. “I don’t care what you think,” Orban told her, “but I am going to protect my borders even if it becomes necessary to build fences all around my country.” He added, “I will not accept your moral imperialism.” As Drozdiak describes it, “Merkel shoved her papers aside and stared icily across the vast conference table” in Brussels where EU leaders often gather in emergency sessions.

“I grew up staring at a wall in my face,” the East German-raised Merkel told Orban, with unaccustomed emotion. “And I am determined not to see any more barriers being erected in Europe during the remainder of my lifetime.” The other heads of European governments, reports Drozdiak, “sat back in stunned silence as they absorbed her message and realized how Merkel’s fierce determination to maintain open borders for the refugees had become for her a personal test of humanitarian morality,” as Drozdiak accurately puts it.

Merkel paid a steep political price for her moral action; perhaps it will even be seen eventually as the source of her political defeat. I dwell on this refugee story (while I’ll skip over much of the rest of the content of Fractured Continent), because it likely explains more about populism and rejuvenated nationalism than any other single issue on the European crisis agenda.

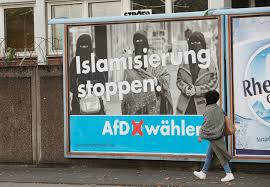

AfD anti-Muslim billboard.

Eventually, Merkel beat a humiliating retreat on the refugee question, striking a questionable deal with Turkey to stem the tide of migrants, and yet even that didn’t prevent the rise of sizeable anti-immigrant demonstrations, followed by a political party, the Alternative for Deutschland (AfD), whose platform was primarily focused on the immigration issue. The AfD won representation in numerous German state elections through 2016, and in the 2017 federal election gained 13 per cent of the vote, a breakthrough for a far-right party not seen since the era of Hitler, making it the third largest party in the German parliament.

That the topic of immigration, cultural strangers, and refugees has become the most visible issue in the rise of right-wing and “patriotic” movements and parties in Europe, even as some of the economic stress on the EU has abated, is, in a sense, a curious phenomenon.

First, support for anti-migrant policies is in inverse proportion to nativists’ contact with newcomers: in Germany, the AfD scored its best results in provinces with the fewest immigrants, suggesting that the opposition is often based on sensationalist rumours. Second, despite the considerable number of immigrants, they still constitute a fairly small proportion of the population. What’s more, in countries like Germany, where there is an aging population, there’s an actual need for new labour inputs.

Anti-immigrant Brexit poster, featuring UK Independence Party’s Nigel Farage.

Yet, in countries as various as the U.K., Germany, and Poland, the spectre of immigrants has provoked a kind of panic. I mention this because much of the resentment of, and fears about immigrants has been “explained,” even in parts of the liberal press, as a rational discontent. But the case for it being a reasonable worry is, in fact, hard to make. As is generally the case, Drozdiak offers substantial information about this and other relevant topics.

Former British Prime Minister David Cameron.

In each of the places Drozdiak investigates, he provides knowledgeable portraits; he knows and interviews many of the players; finally, Fractured Continent is thoroughly readable and not in the business of axe-grinding, unless being in favour of democracy is now considered mere partisan ideology. In Britain, Drozdiak tells the story of the extraordinary blunder by former U.K. prime minister David Cameron, who unwittingly focused what had been merely cranky and scattered animus against the EU into a “leave” movement capable of winning a referendum and pulling Britain out of the European consortium. It cost Cameron, an otherwise skilled politician, his political career.

(l.) Jaroslav Kaczynski, (r.)v Viktor Orban.

In Warsaw, Poland, Drozdiak deftly traces the rise to power of the right-wing Law and Justice Party (PiS) and its twin brother leaders, the late Lech Kaczynski (who died in an air crash) and his sibling Jaroslaw, who prefers to rule Poland from behind the scenes, holding only the office of ordinary MP. In what Drozdiak describes as a “spartan office in central Warsaw, located above a pool hall and next to a Japanese restaurant, Kaczynski sits hunched behind a heavy dark desk,” from where he has transformed the Polish judiciary, media, and parliament into a nationalist-“patriotic”-Catholic virtual autocracy.

Rome.

Perhaps the most poignant and precarious story is that of Italy and its “eternal city,” – “forever in decline?” Drozdiak asks – mafia-ridden Rome. The crime cartel, according to 2014 indictments, controls Rome’s garbage collection and much of the rest of the civic infrastructure, various traditional underworld businesses, and one of its prime current money-makers, running the refugee centers for more than 300,000 desperate immigrants who have poured into the country in recent years. That there even is a lucrative “refugee camp business” perhaps tells us more than we want to know about the condition of Italy. Worse, the mobsters have been far less competent when it comes to providing civic services than the traditional sclerotic Italian bureaucracy. The joke in Rome, Drozdiak tells us, is that there’s no worry of an ISIS attack, because the terrorists could never get through the piled-up garbage. But it’s no joke that should Italy’s economy, the fourth largest in the EU, fall, the rippling effects could easily imperil the entire Eurozone.

What gives the Italian story its particular tinge of political sorrow is that there was an alternative on hand. After years of misrule by media mogul Silvio Berlusconi (a precursor to the vulgarities of Donald Trump in the U.S.), the Italians finally shoehorned into office a series of fairly competent technocrats, and even a promising youthful prime minister, Matteo Renzi, the 39-year-old former mayor of Florence, now at the head of the center-left Democratic Party, who vowed to clean up the country and bring in overdue and much-needed reforms. Drozdiak brings the necessary sobriety to the tale of an ultimate political failure that swept Renzi from office, and in an interview with one of of Renzi’s technocrat predecessors, Mario Monti, makes clear how much the refusal of the E.U., and particularly Germany, to undertake realistic continent wide debt-sharing contributed to the precarious state of Italy and other E.U. members.

By and large, Drozdiak leans toward a worse-case scenario view of the collective state of the nations that make up the European Union. Yet, although there was much justified foreboding about 2017, it turned out that the worst case was not necessarily the case. In the Dutch elections of spring 2017, Geert Wilders and his Freedom Party scored only 13 per cent of the vote and there was never any possibility that Wilders would end up in a government coalition, much less that he would lead it. Stll, coalition negotiation dragged on for a painful nine months before the former conservative prime minister Mark Rutte – his Freedom and Democracy Party took 21 per cent of the vote – was re-elected to the post as the head of a 4-party coalition. Similarly, in France, a 39-year-old relative unknown, Emmanuel Macron, emerged at the head of the newborn En Marche! political group, and handily defeated both mainstream parties and Marine Le Pen of the National Front to win the French presidency.

All of this was enough to induce a sigh of relief in Berlin, Brussels and other European capitals, but it in no way meant that the tide has turned against right-wing populism. As noted, a far-right party in Germany registered a comparative electoral success, Austrian parliamentary elections resulted in a conservative-far right coalition, negotiations to carry out the Brexit decision stumbled along in Brussels, the drumbeat around immigration issues was not silenced, Hungary and Poland continued along a revanchist path, and forthcoming elections in Italy next month promise at best a variety of uncertain and possibly chaotic outcomes. The circumstances are sufficient to take Drozdiak seriously as a contemporary version of the classic 19th century Baedeker guidebooks to the Grand Tour of Europe.

At the same time, this isn’t the moment to give in to despair, we are told. At the Davos economic conference at the end of January, Macron, Merkel and others insisted that “Europe is back.” An improving economic situation across Europe has also improved the political mood. “If we want to avoid fragmentation of the world,” said the French president, Macron, “we need a stronger Europe, it’s absolutely key.”

Even Germany’s Merkel, despite being embroiled in internal coalition negotiations, reaffirmed her commitment to creating a transnational banking system that shares the risk of financial breakdown across borders, a structure that Germany has been accused of stymieing rather than supporting. “We have to ask ourselves,” said the German chancellor, “when we have fewer and fewer people who remember these events of history, have we learned the lessons of history?” She added, perhaps alluding to Trump’s “America First” strategy, “We think that shutting ourselves off, isolating ourselves, will not lead to a good future. Protectionism is not the answer.” (Peter Goodman, “Europe Is Back. And Rejecting Trumpism,” New York Times, Jan. 24, 2018.) While the worst-case scenarios envisaged by Drozdiak will keep thoughtful people up at night, those outcomes are not inevitable – at least, that’s what Europe’s leadership is still stubbornly hoping.