Letter from Berlin: History, Cont’d.

Berlin — Given the historic events in Paris in the second week of January 2015, it’s kind of a shame that former neoconservative American political thinker Francis Fukuyama wasn’t right when he proclaimed “The End of History” in a 1989 essay of that title. For those understandably overwhelmed by the recent horrors, it might provide some perspective to recall that a little more than a quarter-century ago, as the Berlin Wall came down, Fukuyama declared:

“What we may be witnessing is not just the end of the Cold War, or the passing of a particular period of post-war history, but the end of history as such: that is, the end point of mankind’s ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.”

Ah, if only. But after the tragic drama in Paris that saw the slaughter of 17 people by three Islamic terrorists — self-proclaimed adherents of Al-Qaeda and the Islamic State — more than a few people may be feeling that we’ve all had a little too much History of late. The terrorist attacks began January 7 at the offices of the French satirical magazine, Charlie Hebdo, where the magazine’s editor Stephane (“Charb”) Charbonnier was among a dozen people — cartoonists and others (including two policemen, a maintenance worker, a proofreader, and a visitor to the publication) — who were gunned down by a pair of brothers, French-born Muslim extremists in their early 30s, offended by the magazine’s allegedly blasphemous cartoons about the Prophet Mohammed.

In a related but separate attack two days later, on Friday, January 9, as French police were closing in on the Charlie killers, a third Islamic jihadist, who had earlier shot and killed a young policewoman, opened fire at a Jewish supermarket, slaying a worker and three shoppers, and in the process demonstrating that the events in Paris were not limited to an attack on freedom of expression, but were also an Islamist anti-semitic assault on Jews. As the headline of Jonathan Freedland’s column in the Guardian newspaper put it that day, “First they came for the cartoonists, then they came for the Jews.”

In the end, the three terrorists themselves were killed in two separate police operations. Two days later, a nation still stunned by the most violent incident to occur on its soil in half a century, pulled itself together for a Sunday afternoon rally of “unity” and mourning attended by more than a million Parisians and visitors, and led by French President Francois Hollande, who was joined by a legion of government leaders from throughout the region — from neighbouring Germany and England, to Turkey and Ukraine, to Israel and Palestine — all of whom refrained from the usual political speechmaking, and confined themselves to a dignified walk through the streets of Paris.

2.

Add to all that a number of worries, both within and beyond the continent’s boundaries, that mark a particularly uneasy European winter. Here in Germany, since autumn 2014, there has been a wave of anti-immigrant demonstrations and counter-demonstrations, fomented by a group called “Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamization of the West,” known by its German acronym as the Pegida movement. This latest political phenomenon, a populist mixture of rightwing extremists and disaffected supporters of Chancellor Angela Merkel’s governing Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and other centre-right formations, is centred in Dresden, the capital of the province of Saxony in eastern Germany.

Pegida is something new in Germany, although rightwing, anti-immigrant formations have been widespread throughout Europe — in England, France, the Netherlands amd elsewhere — in the past decade. Some of them, such as UKIP (United Kingdom Independence Party) and France’s National Front, led by Marine Le Pen, have attained a degree of elected political power; in Hungary, a far rightwing party, Fidesz, holds elected majority power, and controls, with support from an even more rightwing group, Jobbik, more than two-thirds of the Hungarian parliament. Until Pegida, such groups had been confined to the extreme right fringe in Germany, their unstable regional and national political groupuscules polling in the single digits.

Some two decades ago, in the early 1990s, shortly after German re-unification in 1990, there was a brief spate of attacks, both verbal and physical, against immigrants, mostly perpetrated by neo-Nazi skinheads. While the violent incidents received exaggerated international coverage at the time — the usual “spectre of Nazism” reportage — most observers in Germany knew that the outbursts were neither likely to threaten German democracy nor did they presage a recrudescence of irredentist Nazi sentiment.

By contrast, Pegida is a media-conscious effort to put a polite and popular face on a rightwing formation that holds xenophobic views similar to their European counterparts. The Dresden-based group has held weekly Monday rallies for the last few months (in imitation of the dissident East German protest rallies held in nearby Leipzig in the late 1980s), drawing gradually increasing crowds. Two days before the shootings in Paris, the Pegida march in Dresden attracted some 18,000 participants.

However, efforts to turn Pegida into a pan-German phenomenon have so far fizzled. Attempted rallies in Berlin, Cologne, Leipzig and elsewhere have drawn only small turnouts that were vastly outnumbered by thousands of counter-demonstrators. In Berlin, the local government turned out the lights at the city’s iconic Brandenburg Gate to signal its opposition to the rightwing rally; the same thing happened at Cologne’s famous cathedral; even in Dresden itself, at a city-and-province-sponsored anti-Pegida solidarity rally on the Saturday after the Paris attacks, some 35,000 people participated, twice the number of the previous Pegida turnout. Moreover, the German government, from Chancellor Merkel to her various ministerial spokespeople, continues to speak out strongly against Pegida. In a national New Year’s address criticising the anti-Islam protestors, Merkel declared, “I say to all those who go to such demonstrations: do not follow those who have called the rallies because all too often they have prejudice, coldness, even hatred in their hearts.”

Whatever’s in their hearts, the movement’s organizers know that their message falls on potentially receptive ears. Pegida may currently be no more than a quirky regional manifestation in a province, ironically, that has one of the smallest immigrant contingents in the country, about 2-3 per cent of Saxony’s 4.3 million inhabitants, compared to the more than 10 per cent of citizens with immigrant backgrounds nationwide. But recent polls conducted by the Bertelsmann Foundation found that a majority of Germans (57 per cent) thought that Islam was threatening to German society.

The real frontlines of the immigration debate may be taking place not in the streets of German cities but in German classrooms where a patchwork of programs is aimed at the “integration” of recently-arrived young refugees and immigrants. Although in the same Bertelsmann poll cited above, a majority of German Muslims say they feel “integrated” into German society, the murky criticisms that they aren’t — a mixture of partial truths and resentful fantasies — are widespread.

A longtime Berlin friend of mine, who teaches in one of the integration programs in a local high school, reports that young refugees from Syria, or from Roma gypsy communities, tend to be more traumatized than their counterparts of a few years ago, many of them having grown up in societies where almost all education systems have ceased functioning along with much else of the social infrastructure. There’s a legitimate criticism to be made of the situation, he says. It’s that the German state, which has, since the Yugoslavian Wars of the 1990s, taken in more refugees than any other country in Europe, has yet to commit to the kind of educational funding and organizational oversight necessary to provide real integration and not just a facade. What’s needed, most likely, are teaching teams that consist of not only specialist teachers, but psychologists and other social workers. The idea itself is straightforward enough. The integration programs should teach young immigrants to speak German and should foster an understanding of German constitutional values that promote what German philosopher Jurgen Habermas calls “constitutional patriotism.” If such programs can be made to work, they will, in addition to doing some good, expose the anti-immigrant protestors for what they most likely are.

3.

Pegida unwelcomely arrives in the midst of a slew of other troubling concerns, including renewed European economic anxieties caused by incipient deflation, as well as worrisome, persistent political conflicts that geographically range from as near as the Russian-Ukrainian border, to the ongoing Syria-Iraq Middle Eastern conflagration, to the terrorist attacks of another Islamicist group, Boko Haram, in once-distant Nigeria. For some, the relentless Continuation of History may well be producing a sigh-inducing moment of “history fatigue.”

To be fair to the much-derided Francis Fukuyama, who in subsequent years moved toward the American political centre (eventually voting for Barack Obama in 2008), he did attempt to make a distinction between “events” and “history.” Events, including acts of barbarous regression, would continue, he conceded, but history itself, he insisted, had come to an ideological culmination. That’s a heads-I-win-tails-you-lose way of being right, I suppose, but in fact, it’s not just the horrors of last week that remind us that “the final form of human government” is far from historically settled.

Even in the terms in which Fukuyama was thinking in 1989, the notion of “the universalization of Western liberal democracy” as the End of History was overblown and simplistic. The idea elided the reality of the inequalities of the capitalist economic system embedded within “liberal democracy,” more or less ignored the looming ecological catastrophe that is largely a byproduct of capitalist democracy, said little about the barely restrained imperialisms of the American and lesser super-powers, and didn’t foresee that messianic religious movements might have their own ideas about the “final form of human government.” On some days it looks like the dominant if not “final form of human government” will turn out to be not “liberal democracy,” and if not fantasies of the return of a medieval 7th century caliphate, something like the contemporary authoritarian kleptocracy that characterizes President Vladimir Putin’s Russia, or China’s equally corruption-ridden, one-party regime. Indeed, after last week’s mass murders meant to silence the free expression of a group of satirical journalists in the name of a distorted version of religion — events that engendered a now familiar cycle of shock, fear, numbness, anger and grief — history seemed more like a nightmare from which we’re trying to awaken, to paraphrase the novelist James Joyce, than an end point of ideological evolution.

4.

By coincidence, the week of the Paris shootings, I was reading a biography of the American cultural critic and novelist Susan Sontag (1933-2004), who, among other public roles, was the president of PEN, the international writers’ organization committed to free speech and expression. In February 1989, when a death sentence fatwa was proclaimed by the Ayatollah Khomeini, ruler of the theocratic Islamic Republic of Iran, against novelist Salman Rushdie because of his allegedly blasphemous satiric novel, The Satanic Verses, Sontag was one of the few who didn’t hesitate. While many in the West, including writers, vacillated, obfuscated and fudged their responses to the outrage of the murderous decree and pondered aloud the advisability of not offending the sensibilities of religious believers, Sontag immediately convened meetings of PEN in New York to unequivocally defend Rushdie’s right to speak and write.

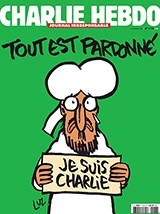

The Rushdie Affair, as it became known, is a reminder, alas, that the modern origins of the theocratic impulse to suppress speech considered offensive to a particular religion — the impulse behind the terrorist attack at Charlie Hebdo — didn’t emanate from a fringe scattering of extremist self-proclaimed executioners, but from a branch of mainstream Islam itself. That long ago event also happens to have a bit of personal resonance. Inspired by acts of resistance to murderous religious dictates, such as those led by Sontag and PEN, I, along with a friend, the late playwright Tom Cone, organized a public meeting in Vancouver of local writers, a rare get-together of scribes of all different genres — poets, playwrights, novelists, journalists, cartoonists — to express our solidarity with the beleagured Rushdie. At our minuscule and no doubt mainly rhetorical contribution to History, I remember that we donned buttons and T-shirts, proclaiming, “I Am Salman Rushdie,” just as today, people in Paris and around the world are displaying “Je Suis Charlie” (“I Am Charlie”) signs, clothing and other paraphernalia.

It’s become customary — indeed, almost obligatory these days, if you’re a left liberal type — to preface any discussion of Islam and terrorism with the assurance that the fringe of terrorists is not to be conflated with the more than a billion sensible Muslims around the world, and that in combating the terrorists we must be vigilant not to scapegoat ordinary, non-violent, moderate (add the approving adjective of your choice here) Islamic believers among us. No doubt that’s all well and good, even if obvious (but apparently not obvious enough to the bigots among us).

Still, there’s something to say about reason and unreason in Islam. In the flood of commentary inspired by the Charlie Hebdo attack, more than one columnist — I think the one I was reading was the New York Times’ Nicholas Kristof — rhetorically asked, “Is Islam to Blame?” (for the terrorist events in Paris and elsewhere), only to quickly absolve the vast majority of ordinary, moderate, non-violent, Muslim believers … well, you know the politically polite, as well as “politically correct,” drill.

But the Ayatollah Khomeini’s fatwa continues to nag, a quarter-century later. The decentralized theological authority of Islam (like that of Western Protestantism) means that almost any local hero can set up shop and preach whatever he pleases in the name of Islam on a Friday afternoon at his neighbourhood mosque or website. The terrorists who attacked Charlie Hebdo claimed theological allegiance to the jihadist rants of Anwar Al-Awlaki, the American-born, Yemen-based cleric who was assassinated by an American drone strike in 2011.

Since “Islam” is a diffuse doctrine, the interpretations of the Quran are many. What for some is a holy book proclaiming peace and love, is for others a command to subdue the infidel, by violent means if necessary, and to ensure the submission of all to Allah. Yeah, replies the reasonable flock, but no one (meaning, no one in their right mind) takes that sort of thing seriously, it’s just like the bloody commands in the Old Testament to head off into the next valley over and slay unbelievers down to the last man, woman, and child. The problem is, there are just enough literalists (as there are inerrantists in Christianity) who take that stuff all too seriously. Even as moderate Muslims throughout Europe were decrying the Paris terror, and insisting “not in my name,” down at the south-eastern end of the Mediterranean pond in orthodox Saudi Arabia, a local sharia-law judge was implementing the first 50 of a 1,000-lash flogging sentence against some hapless blogger accused of insulting the Prophet or somesuch fantasmal crime.

You only hear semi-serious consideration of the question, “Is there something wrong with Islam?” on the late-late-night talk shows — the one I was watching sometime over the weekend was an HBO production hosted by anti-religious comic Bill Maher and featuring fatwa survivor Salman Rushdie, still alive, slightly plump, and not crazy after all these years. Rushdie, in a statement published in the Wall Street Journal on the day of the Paris shootings, was prompt to declare, “Religion, a medieval form of unreason, when combined with modern weaponry becomes a real threat to our freedoms. This religious totalitarianism has caused a deadly mutation in the heart of Islam and we see the tragic consequences in Paris. I stand with Charlie Hebdo, as we all must, to defend the art of satire, which has always been a force for liberty and against tyranny, dishonesty and stupidity. ‘Respect for religion’ has become a code phrase meaning ‘fear of religion.’ Religions, like all other ideas, deserve criticism, satire, and, yes, our fearless disrespect.”

Maher goes even further. He claims that while few Muslims would carry out terrorist attacks like those in Paris, nonetheless “millions” of Muslims, in the Cairo-Damascus-Baghdad and other streets, support such acts. Maher, who made the anti-faith documentary, Religulous, takes his criticism beyond Islam. As he said in one interview, “We have to stop saying, We shouldn’t insult the ‘great religions.’ First of all, they aren’t great religions, they’re all stupid and dangerous.”

The line gets Maher a laugh on past-bedtime TV. But the answer to the rhetorical question, “Is there something wrong with Islam?”, is probably, “Yes, what’s wrong with Islam is that it’s likely to be a false belief, and worse, it’s a false belief that goes unchallenged.” It’s probably also true that most other religions are based on false beliefs, but it especially seems to be the case, at least in public spaces, that the fundamental doctrines of Islam are rarely challenged, and since the fundamental doctrines seem to be so easily and frequently twisted into fundamentalist doctrines, it would make sense to more often ask aloud if it’s likely that these particular religious beliefs are true.

What sets the other religions slightly apart from Islam is that everything from Catholicism to Mormonism and Scientology are publicly challenged in Western society on a daily basis. All of the religions, Islam included, are a jumble of creation fantasies and bizarre prescriptive rules based on the antiquated ideas of mostly tribal societies during pre-scientific, pre-rational eras. The unusual thing that happened with respect to Judeo-Christian beliefs is that for more than a hundred and fifty years now, ever since Darwin, people have been boldly asking, “What makes you think that a God exists? What makes you think your normative rules are justified?” As a result, throughout most Western societies, there are today substantial portions of the population who reject orthodox religious beliefs. That simply hasn’t happened in the world of Islam. There are some Islamic dissidents, of course, but for the most part their voices have been silenced and they have been punished, often in barbaric ways. Criticism of Islamic beliefs, either from inside or outside Islam, have not been tolerated. And that’s a dangerous problem.

Because there’s so much deference to, sensitivity about, and sentimentality toward religious belief these days, rather than a useful, frank examination of long-standing, but possibly bizarre fantasies about the creation and meaning of human life that constitute so much of religious belief, we’re more likely to get drawn into side issues. In the extensive commentary since the events in Paris, there have been earnest debates about whether there are limits to free speech and good taste that the Charlie Hebdo cartoons have transgressed, and equally futile discussions about whether one is required to reproduce the Charlie caricatures in order to display genuine solidarity with the memory of the murdered cartoonists. In the week since the shootings, I’ve been surprised by the number of people who want to use the occasion as an opportunity to point out everything from the fact that U.S. drones kill children in Pakistan to the murders of uncounted numbers of indigenous women in Canada to the complaint that the Boko Haram mass murders in Nigeria didn’t get as much press attention as the killings in Paris. All these tragedies are no doubt discussion-worthy, but in the context of what happened in Paris, insisting on belabouring their importance now only diffuses the focus on, and undercuts the meaning of the attack on Charlie Hebdo.

5.

So, to recall the name of an old TV satirical news program, That Was The Week That Was, a traumatic week that many might have wished had never been at all, culminating in a surge of humanity defendng, however inchoately, a kind of generic humanism. The more than million-person demonstration in the famed squares of Paris — a logistical and security nightmare for some 6,000 police and military personnel guarding it — turned out to be remarkably understated, dignified, of course non-violent, and unexpectedly moving. The politicians refrained from grandstanding, made no speeches, and simply walked briefly in the streets of Paris in linked-arm formation.

The always slightly cynical pundits were quick to assure us, however, that this show of national mourning and “unity” would fracture before nightfall. One shrewd French sociologist asked if we supposed that unemployed, disaffected, often Muslim, young people in the downtrodden banlieues around Paris were likely to be demonstrating in Paris that day. By the Monday after the Sunday show of unity, Pegida’s weekly anti-Islamic march in Dresden, attracted a record 25,00o participants, although attempts at similar demos everywhere else foundered, and Chancellor Merkel committed to appearing the next day at a Muslim-sponsored vigil at Berlin’s Brandenburg Gate.

Meanwhile, as the too-knowing in the media continued to debate whether or not they were willing to declare, “Je suis Charlie,” Charlie Hebdo, a week after the killings, promptly published its new issue. Yes, with a cartoon of the Prophet on the cover.