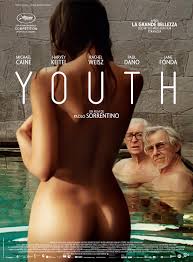

Forever Old

Paolo Sorrentino, Youth (2015).

Although old people supposedly “dwell in the past” – too much, it’s implied – in 45-year-old Italian director and screenwriter Paolo Sorrentino’s sumptuous meditation on age, art, mortality, and other mysteries of life — which he cheekily titles Youth (2015) — the elderly protagonists recurrently point out that the past is not so much a dwelling place as a part of reality that becomes increasingly distant for the old, even to the vanishing point. As the songwriter-singer Leonard Cohen put it not too long ago, “I thought the past would last me / But the darkness got that, too.” (Leonard Cohen, Old Ideas, 2012).

Or, as Fred Ballinger says, “I’m thinking about the things you forget over time. I don’t remember my parents any more. What they looked like, how they talked.” Ballinger, an 80-something retired British modernist composer, is strolling through a springtime alpine valley with his agemate-buddy, the septuagenarian American filmmaker Mick Boyle.

They’re in the Swiss Alps near Davos, where the two are taking an annual holiday at the Grand Hotel Waldhaus. It’s a posh resort/spa/rehab centre – an updated “wellness” version of the Magic Mountain sanitorium of Thomas Mann’s eponymous 1924 novel.

Ballinger adds, referring to his adult daughter and assistant, “Last night I was watching Lena as she slept and I started thinking about all those little things, thousands of them, that I did for her as her father. I did them deliberately, so that she would remember them when she grew up. But in time she won’t remember a single one.” He concludes, “Tremendous efforts, Mick. Tremendous efforts, and all for the most modest results. That’s the way it always is.” He’s likely thinking about more than child-rearing.

Michael Caine.

In a career-performance, Michael Caine, 82, plays Ballinger with ineffable sadness, melancholy apathy, and “polite disenchantment,” while Harvey Keitel, as Mick, provides not only suitable palsy-walsy chemistry, but a desperate contrasting energy as he and a young production team work on the script of his latest project, a final “testament” of a film called “Life’s Last Day.” The whole thing depends on the participation of Boyle’s actress-muse, Brenda Morel, the star of a dozen of his previous films. She’ll turn up much later, in a startling bravura performance by, of all people, 78-year-old Jane Fonda.

But it’s Ballinger’s disengagement, deflecting the carnival-cum-purgatorio of magic mountains, meadows and mud baths, that’s the focus of Youth. “Polite disenchantment” is Guardian film critic Peter Bradshaw’s apt phrase, applied to Toni Servillo’s star performance in Sorrentino’s last film, The Great Beauty (La Grande Bellezza, 2013), which won an Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film. It’s a phrase that applies to almost anyone who’s playing the elderly lead of a Sorrentino pic.

Michael Caine, Paolo Sorrentino.

For those not familiar with his work, Sorrentino began making films around the turn of the millennium and, with The Consequences of Love (2004), an existential mafia drama, he began to be seen as a director of national importance in Italy. But it wasn’t until Il Divo (2009), his remarkable film about former Italian Prime Minister Giulio Andreotti and the depth of political corruption in Italy, that Sorrentino attracted international acclaim. This Must Be the Place (2012), starring Sean Penn, was his English-language debut, and the prolific Naples-born artist even found time to pen a novel, Everybody’s Right (2012), that picked up a nomination for Italy’s prestigious Strega Prize. La Grande Bellezza (2013) made Sorrentino an Oscar winner.

It was the latter film that made clear Sorrentino’s profound connection to the Italian film maestro of the previous generation, Federico Fellini (1920-1993). In The Great Beauty, the literate viewer has the paradoxical experience of watching an explicit homage to Fellini’s La Dolce Vita (1960), picking up on almost all the social and spiritual themes of the earlier film, but at the same time, it feels like both an historical update and an “original remake,” if there is such a category. The effect is to produce an optical illusion in which you feel like you’re seeing La Dolce Vita again, but somehow for the first time, and simultaneously a new and completely different film as well. Although the critics regularly invoke Fellini’s name when writing about Sorrentino, what they less frequently recognize is that the use Sorrentino makes of his mentor is neither a pastiche nor an imitation, but a renewed exploration of Fellini’s sensibility. That influence is again visible in Youth, which recalls in part Fellini’s 8½.

Speaking of critics, I probably should report that the estimable Bradshaw is less taken with the disenchantment, polite or otherwise, in Youth, which he regards as “a diverting minor work,” deeply flawed by “a strangely unearned and uninteresting macho-geriatric regret for lost time, lost film projects, lost love, and all those beautiful women you never get to sleep with…” (I’ll get to the dreaded “mixed reviews” in a minute.)

Rachel Weisz.

The beautiful and once-beautiful women in Youth are represented not only by Rachel Weisz as Ballinger’s daughter Lena, pop star Paloma Faith doing a cameo of herself, the aforementioned Fonda, but also by a visiting Miss Universe winner (model Madalina Ghenea convincingly fills out the curves), who has landed a week’s stay in magic mountain country as part of her beauty queen prize.

As for those “you never get to sleep with,” there’s Gilda Black. But she exists only in the adolescent memories of Fred and Mick, our unreliable narrators, and worse, as Mick laments, “The real tragedy — and believe me, it really is a tragedy — is that I can’t even remember if I slept with Gilda Black.” Are you serious? Fred asks, who a minute before had vowed that he would’ve given up 20 years of his life for a night with Gilda. Mick sensibly points out that a night with Gilda would not be worth 20 years of Fred’s or anyone else’s life, but also assures him, “unfortunately yes, I swear,” that memory has failed (which is, given Fred’s potential envy, occasionally a good thing in the name of friendship). And “the love I never conquered / when young will end as such,” as the poet Robin Blaser once summed it up.

There’s a good deal of ruminating here, both banal and wise, but the plotline is concerned with whether or not the composer-conductor (he’s wielded the orchestral baton in New York, London, and in Venice for a quarter-century) can be roused from his lethargy. In the film’s first scene, an obsequious emissary from the Queen of England (played by Alex Macqueen: “Pardon me, Mr. Ballinger… or may I call you Maestro?”) appears in the hotel’s garden, amid the pools, jacuzzis, and chaise lounges, to invite Fred to conduct a performance of his most famous piece, “Simple Songs No. 3,” with the London Symphony Orchestra and a renowned soprano, Sumi Jo, on the occasion of Prince Philip’s birthday (and oh yes, there’s a knighthood in it for the prospective Sir Fred).

To the last offer, Fred replies (in a line from the original script that didn’t make the final cut): “Do you know what Satie said when he was offered the Legion of Honor? ‘It’s not enough simply to refuse it, you also have to not deserve it.’ But I am not Satie.” The unruffled emissary duly notes, “Her Majesty will be delighted to learn you have accepted.” Snaps Fred, “Her Majesty has never been delighted about anything.” As for the Royal Concert, Fred’s thanks, but no thanks, sounds pretty firm. But why not? “Personal reasons,” is the Maestro’s clipped reply. There will be further entreaties.

Lots to see.

But before the renewed Royal Command Performance invitations, there’s plenty of plot and sub-plot to absorb, lots of Swiss countryside to see (skillfully filmed by regular Sorrentino cinematographer Luca Bigazzi), and various enigmatic appearances to riddle through. The composer’s daughter Lena, about to head off on a Polynesian holiday of her own with her husband Julian (Ed Stoppard), who also happens to be Mick’s son, is unexpectedly dumped (hubby has taken up with singer Paloma Faith); Mick and his screenwriting crew will or won’t come up with an ending for the “Life’s Last Day” project; and then there’s the story of Fred’s young actor friend, Jimmy Tree (in a hip turn by Paul Dano, channeling a Johnny Depp type), who’s at the luxury retreat researching an upcoming role that he’ll shockingly dress rehearse in the Waldhaus’s breakfast room. There’s much untangling of Fred’s relationships, especially the mysterious one with Melanie, his unseen wife — except for a photo on a bedside table — is she alive? did she walk out in exasperation? — it has something to do with Venice, but what? Why does Lena remind him that he hasn’t taken flowers to Venice for a decade?

Then there are the apparitions, thematic motifs, and layered details that are essential to Sorrentino’s aesthetic. The filmmaker moves easily between dreams, reveries, bits of magic, and unexpected characters that range from the gorgeous to the grotesque. Just as the queen’s emissary and his assistants are scuttling off, the most remarkable of these apparitions first appears as the massively obese upper torso of a person trying to get out of the swimming pool. As he emerges from the water, so does a giant tattoo of Karl Marx on the back of the 150-kilo man, as he’s aided by his wife, several hotel attendants, and a cannister of oxygen into a poolside deckchair.

Maradona.

Although this larger-than-life figure (played with sweet delicacy by Rolly Serrano) may be something of a mystery to North Americans, he’s instantly recognizable to Latin and European viewers as a representation of Diego Maradona, considered the 20th century’s greatest soccer player, who descended into an afterlife of cocaine, appetite and corpulence. Now, here he is, taking the waters at Magic Mountain, as Fred and Mick and Jimmy Tree and all the rest are sorting out diminishing lives and art. Maradona reappears in subsequent scenes, always a gentle horizontal giant making a subtle intervention, and as with most of Sorrentino’s apparitions, there will be a suitable epiphany.

Or take the tiny matter of left-handedness. Fred is wandering the darkened corridors of his grand hotel, listening to the scratchy opening bars of his “Simple Songs No. 3.” (Fred’s music, which has affinities with the mid-20th century works of Benjamin Britten, is provided by American composer David Lang.) Other elderly people float through the same hallways, with canes, walkers, electric wheelchairs and carts (at one intersection, there’s even an electric cart collision, and an outburst of road rage). Eventually Fred finds the source of the familiar sounds, and enters a half-open door where the chambermaid is just finishing tidying up. A 12-year-old boy is sawing away on a violin.

“Do you know who composed the piece you’re practicing?” Fred asks. “No, who?” the boy replies. “Me,” says Fred. “I don’t believe you. What’s it called?” the boy challenges him. “It’s called ‘Simple Song No. 3.” The boy checks the title on the cover of his score, and admits, “You’re right. And what’s the composer’s name?” “Fred Ballinger,” Fred says. “And you, what’s your name?” asks the boy. “Fred Ballinger,” says Fred. “You can check at the front desk. I’m staying here.” There’s more to this innocent exchange, but the poignant detail comes at the end, after the boy has resumed playing. Fred interrupts him, asking, “May I do something while you play?” And when the boy dubiously gives his permission, Fred steps timidly into the room, touches the boy’s left arm, the one holding the bow, and raises the boy’s elbow an inch, correcting his position. “There,” Fred says, and returns to the corridor, hearing the improved sounds the boy now makes.

A few scenes later, Fred and Jimmy Tree are floating in the swimming pool when the boy violinist appears. “I wanted to tell you,” the boy says to Fred, “that I checked at the front desk, and you really are Fred Ballinger.” “I’m glad you set your mind at rest on that score,” Fred allows. There’s something else the boy wants to tell Fred: “I wanted to tell you that ever since you corrected the position of my elbow, I play better.” “Do you know why?” Fred asks. “Because you’re left-handed. And left-handed people are irregular, so an irregular position helps.” At which point the cetacean-sized Maradona surfaces in the pool to say, “I’m left-handed too.” And Jimmy Tree replies, “Christ! The whole world knows you’re left handed.”

As all devout soccer fans will recall, this arcane in-joke refers to the 1986 World Cup quarter-final when Maradona scored a crucial goal that he was accused of illegally deflecting into the net with his left hand rather than properly hitting with his head. The goal was nonetheless allowed, and at the post-game press conference, Maradona jokingly remarked that the goal was scored “a little with the head of Maradona and a little with the hand of God,” and ever after it became known as the “Hand of God” goal. (Maradona’s team, Argentina, went on to win the World Cup that year. Cf., Wikipedia, “Argentina v England [1986 FIFA World Cup],” accessed Jan. 26, 2016.) You don’t have to know any of this inside football stuff to get the point of the former sports idol or of the riff on left-handedness. The exquisite treatment of an otherwise insignificant motif, one of several in the film, is an example of the texture that Sorrentino brings to his art.

By now, it’s time for a renewed entreaty. The emissary has returned to his suit. In the face of Fred’s continued resistance, the exasperated Queen’s man bursts out, “I just do not understand. What exactly is the problem?” This time he pierces the composer’s shell that protects a passionate grief. Without polite detachment, Fred shouts at him, “The problem is that those Simple Songs were composed for my wife. And only my wife performed them, only my wife recorded them. And as long as I live, my wife will be the only one to sing them. The problem, my dear sir, is that my wife can’t sing any more. Now do you understand? Do you?”

There will be considerably more to understand before Sorrentino is finished. Rest assured, there are denouements all around, and epiphanies aplenty, none of which should be revealed here.

In one scene, Mick takes his clatch of young screenwriters up to an alpine lookout point and invites a young woman in the crew to look through the telescope. “Do you see that mountain over there?” “Yeah, it seems really close,” she observes. “That’s what you see when you’re young,” Mick says. “Everything seems really close. That’s the future.” He invites the girl to look through the telescope from the other end, at the faces of her friends. They appear, of course, far away. “And this is what you see when you’re old. Everything seems really far away. That’s the past,” says Mick. Well, perhaps it’s more simplistic than simple in this instance, but the point is made.

In one scene, Mick takes his clatch of young screenwriters up to an alpine lookout point and invites a young woman in the crew to look through the telescope. “Do you see that mountain over there?” “Yeah, it seems really close,” she observes. “That’s what you see when you’re young,” Mick says. “Everything seems really close. That’s the future.” He invites the girl to look through the telescope from the other end, at the faces of her friends. They appear, of course, far away. “And this is what you see when you’re old. Everything seems really far away. That’s the past,” says Mick. Well, perhaps it’s more simplistic than simple in this instance, but the point is made.

Although Youth swept the European Film Awards held in Berlin last December, winning best picture, best director, best actor (Michael Caine) and even a best actress nomination (Rachel Weisz), its points, both simple and not-so-simple, have been largely lost on American and English critics, including ones I usually respect, many of whom found Youth “pretentious,” “prosaic,” and worse. The upcoming Academy Awards pretty much ignored it, offering only a token nomination for an award to David Lang’s “Simple Song No. 3,” and even that may have been more of a gesture than anything else, Hollywood’s obligatory nod toward “culture.”

The New York Times’ A.O. Scott wrote, “We are here to contemplate a civilization that has been declining, with sighs and kisses and world-weary lyricism, for a very long time… a landscape pocked with signifiers of European Decadence, one of the continent’s most durable and distinguished exports.” He’s not sure he wants to attend another “Come-Dressed-as-the-Sick-Soul-of-Europe Parties” (the phrase is legendary critic Pauline Kael’s coinage). Scott finds the dialogue clunky, and that David Lang’s music “carries the intimation of something deeper and grander into this minor fable of waning potency.”

In the end, says Scott, “The film starts to feel like an airline magazine collaboratively produced by the editorial staffs of Playboy and Modern Maturity.” (A.O. Scott, “Sorrentino’s Youth: A Euro Buddy Film,” New York Times, Dec. 3, 2015.) Well, I don’t know about reducing this film to a scenic spread from an in-flight magazine. Given that we know that Sorrentino is capable of delivering the gritty details of sub-lunar politics and other current events (see Il Divo), I take it that his “out of the world” Magic Mountain setting for the metaphysical contemplations of Youth is intended. (On a lighter note, when I innocently Googled the Grand Hotel Waldhaus to check a fact, the advertising algorithms kicked in, and I’m currently being offered, while reading the Times or scrolling Facebook, persistent deals that will let me bunk down at the Waldhaus for a measly $361 a night.)

The Toronto Globe and Mail reviewer suggested that the line in the film, “tremendous efforts and all for the most modest results,” ought to be applied not to child-rearing or art, but to “the ambitious but lackluster new film” at hand. As for cinematic influence, we’re warned that “if you love the films of Federico Fellini, you’ll probably hate Sorrentino, who seems to throw all the good parts of Fellini into a blender and hit puree.” Ouch. (Ty Burr, “Aging artists, Swiss scenery, and a touch of Fellini,” Globe and Mail, Dec. 10, 2015.) Other critical comments and slurs ranged from “pretentious phantasmagoria” to downright “drivel.”

Even critics who approved, like Richard Roeper, admit that “it’s a lot of movie squeezed into one movie.” He adds, “Yet how much better is it to experience a film overflowing with so many elements than one that has to stretch its content just to get to the finish line?” (Richard Roeper, “Dazzling Non-Sequiturs,” Chicago Sun-Times, Dec. 10, 2015.)

Although the aggregate review site Rotten Tomatoes reported a majority of favourable reviews for Youth (about 70 per cent), the critics who disliked it really disliked it, with barely restrained vehemence. Some of the objections are understandable. Youth doesn’t contribute much to our knowledge of the other 99 per cent. Nor does it help solve Hollywood’s current “diversity” problem. And it’s definitely about live-but-almost-dead-white-European-males. Sorrentino is not only politically incorrect, but worse, he seems indifferent to the entire notion.

The collective impatience and grumpiness about this film, some of which comes from critics who enthusiastically applauded Sorrentino’s similarly-themed Great Beauty, gave me pause. Admittedly, I’m predisposed toward Youth. In part, that’s because of my acquaintance with Sorrentino’s previous films. But maybe it’s also because this is one of the few films of this season’s crop whose main characters share life circumstances similar to my own. Most films I’ve seen about old people are either sentimental, maudlin, or falsely redemptive. This one isn’t.

I’m willing to consider the possibility that Youth may be a film more appreciated by people for whom the end of the human condition is slightly more pressing than for a general audience, but I’m inclined to reject that notion, and stick to the convictions of my viewing experience. Having seen most of the Best Picture Oscar nominees for 2016, Sorrentino’s unnominated film seems to be as interesting as any of the contenders. I was going to say more interesting than most everything else on offer, but why start pointless quarrels? It’s enough that it’s good enough to engage one’s attention, if, that is, you’re paying attention.

Youth.

Sorrentino’s enigmatic title may echo those of Joseph Conrad or Leo Tolstoy, each of whom also created a work called Youth. Or maybe the title merely refers to a scene much-remarked by the critics where a nude Miss Universe strides into the pool past the huddled senior artist protagonists who allegedly gaze with stricken longing for lost potencies. But, actually, the only time the word turns up in the film is when Fred is being assured by the spa doctor who’s done a battery of tests on him that “you’re as healthy as a horse.” Not even a prostate problem? Not even that.

“So I’ve grown old, but without understanding how I got here,” Fred notes. “Um… do you know what awaits you outside of here?” the doctor asks. “No, doctor, what?” Fred wonders. “Youth,” replies the physician, with a faint smile, as if he knows the denouement.

Michael Caine.