Cultural Appropriation, Misappropriation and Cultural Exchange: A primer

The polarizing issue of whether or not writers can borrow, steal or otherwise employ materials from cultures that aren’t the one they were born within has re-emerged in the midst of Canada’s cultural community. The issue has been around since the 1980s, but this time the knives are sharper, stakes seem to be greater, and the din of axes being ground is making it hard for anyone to listen to anyone else.

In Canada, the leading edge is aboriginal: they’re angry at the chronic legal and cultural interference of governments, and just as angry about its patronizing indifference to their cultural aspirations and their economic quality of life. The aboriginal artistic community has grown in both numbers and vitality, and is now making broad and often unspecific proprietary claims on aboriginal culture, past and present.

At times it seems that reactions from the larger Canadian community come from three distinct sources. From the left there is support, mostly rhetorical, on quasi-Marxist grounds: that the privileged white community is still conducting the same imperialist program of land theft and cultural genocide it has for 400 years. Little to no distinction is made between the frankly genocidal program of white settlement and aboriginal resettlement carried out in the United States, and Canada’s significantly less violent but not much less cruel attempts to assimilate its aboriginal peoples.

The political and social right mostly just overreacts to aboriginal self-determination as a threat to property rights and social custom, which translates, when the threat seems pressing, to claims that free speech is under duress.

Most Canadians squirm between those radicals, sometimes pretending that the system is working, but more often irritably trying to make the system do what it’s supposed to: they want to treat aboriginal people better than their predecessors have, and they’re prepared to pay the price. But they don’t want to be shouted at all day, don’t want the wheel of privilege simply turned 180 degrees. They’ve got doubts about where the shouting will end up, in other words, and what kind of citizenship they’ll have if they go along.

Kateri Akiwenzie-Damm.

The current controversy in Canada was ignited when Write, an Internet-based literary magazine produced by the Writers’ Union of Canada, published its Spring 2017 issue, which featured an interview with indigenous poet and publisher Kateri Akiwenzie-Damm, eight “dispatches” by aboriginal writers along with some fiction and poetry by aboriginal writers. The eight “dispatches” were prefaced by a 484 word editorial by Write’s longtime editor Hal Niedzviecki, titled “Winning the Appropriation Prize”.

The editorial’s first two sentences were fine. “I don’t believe in cultural appropriation,” Niedzviecki wrote. “In my opinion, anyone, anywhere, should be encouraged to imagine other peoples, other cultures, other identities.” Then he put his foot in it by proposing that there should be some sort of literary prize for appropriating other people’s cultures, and spent the balance of the editorial stirring that foot. If Niedzviecki had written his editorial tongue-in-cheek, he didn’t signal it, and it clearly wasn’t apparent to any of the early S&A posters on social media. The mass media’s commentariat mostly followed that lead, as it tends to these days.

Hal Niedzviecki.

The editorial therefore triggered a prolonged one-note howl. Niedzviecki resigned as editor of Write; the Union’s executive issued an apology for the editorial; and those who started the yelling kept right on yelling.

Niedzviecki made a stupid error in thinking he could cover the hot-button subject of cultural appropriation in 500 words, and a job-ending error in thinking that, in 2017, he could be flippant about cultural appropriation. It made me wonder what on earth he was trying to accomplish. The Writher’s Union, as a friend of mine calls it, has been walking on eggs over cultural appropriation for decades, and Niedzviecki couldn’t possibly have been unaware of that.

Having effectively set his own pant leg on fire, Niedzviecki didn’t seem to even try to cover either the subject or his ass, the latter of which he should have realized was going to be a target the moment the words “cultural appropriation” crossed his lips, no matter what he said about it. He even tossed gasoline on the flames by not offering a remotely adequate contextualization of what he did say, and compounded that by not providing any introduction to the “dispatches” of the indigenous writers that followed. In short, he presented himself as an oblivious white guy, and he paid the price for it.

I’ve never met Niedzviecki, but I’ve been told that he’s quite a lot more than just an oblivious white guy. What he did reminded me of Dave Hodge’s 1987 career-ending pencil flip on Hockey Night in Canada after CBC’s management pre-empted overtime between Montreal and Philadelphia for The Tommy Hunter show or something similarly thrilling. Hodge’s gesture was pure exasperation, and there was a powerful strain of exactly that in Niedzviecki’s self-immolation.

So what made him so exasperated that he lost his editorial perspective, hung a group of indigenous writers out to dry and got himself fired from a job he’d handled easily for five years? That question made me go back to the issue of Write to reread the “dispatches” written by indigenous writers to see if there was something in them that might have set Niedzviecki off.

What I found was a little odd, but not quite damning. First, the dispatches weren’t as much reportage as they were declarations, mostly but not in every case, of either identity or empowering authenticity. Was that what they were invited to submit? And if so, who did the inviting? Was this Niedzviecki’s idea or was it a top-down editorial imposition, inadequately articulated either to Niedzviecki or to the invited writers?

Second, I noted that several of the declarations by the indigenous writers had a raggedness of expression that suggested they hadn’t been given an editorial workover, and several of them were larded with rhetorical assumptions and self-aggrandizing postcolonialist jargon that any editor would have challenged the writers to clarify. One or two were little more than brow-beating self-advertisements, all of them were afflicted with moral certitude, and not a single one showed the slightest trace of playfulness or an active sense of irony.

I’m no doubt going to get my own ass in a sling for saying this, but if I hadn’t felt obligated to read and take these declarations seriously, I wouldn’t have gotten much beyond the first paragraph of a single one. They simply weren’t trying to communicate with me or anyone else who might not share their assumptions about what is real and important. Didn’t anyone tell them that they’d be talking, mostly, to the middle class white membership of the Writers’ Union of Canada? And if the dispatches weren’t edited, was it Niedzviecki’s negligence or inexperienced writers, drunk on opportunity and the authentication conferred by the heady fumes of the anti-cultural appropriation movement, unwilling to allow a white heterosexual male to meddle with their prose?

What was it that Kurt Vonnegut said? Ah, yes. Something about the road to good writing being “a good date on a blind date” and keeping “the reader in mind all the time.” In the end I can’t see any evidence that Hal Niedzviecki edited the dispatches, and it’s also pretty clear that Tomson Highway and Tom King didn’t edit them, either. Did I mention that the Writers’ Union of Canada is an organization of professional writers?

Responses to the Controversy

Jonathan Kay.

Within a day or so of Write Magazine’s internal release and Niedzviecki’s departure, a media finger-pointing bee was in full bloom. The next casualty after Niedzviecki, The Walrus editor Jonathan Kay, didn’t object to Niedzviecki’s resignation/firing but said, “What I object to is the shaming, the manifestos, the creepy confessional rituals.” Kay then resigned from The Walrus. Kay may have had little choice about resigning after Ken Whyte, Christie Blatchford, Andrew Coyne and several others over at the National Post’s frat house keyed off Kay’s Twitter remarks about Niedzviecki’s resignation to offer support for actually creating a “Cultural Appropriation Prize”—a fairly dumb provocation under the circumstance, and no one was stupid enough to take it any further.

A few days later Rick Salutin used the controversy merely as an occasion to sideswipe Kay, calling him Canada’s proconsul of manners, (something I think we desperately need) and Marlene NorbeSe Philip posted an unproofed Facebook advertorial that was little more than a summary of her positions over the last twenty-five years, all of which have been hostile to white writers committing acts of cultural theft or even being curious about non-white people and issues without prologuing it with a lot of forelock tugging.

Since then innumerable others have been yapping back and forth about cultural appropriation in the newspapers and on television, and most extensively and hysterically on social media. Probably the sanest piece written about the controversy so far was Venay Menon’s Toronto Star piece of Saturday, May 27 2017, in which he wrote about a pop-up Saturday morning burrito stand in Portland, Oregon that was shouted down and ultimately closed on the grounds of cultural appropriation. The two young women who opened it, it seems, had been touristing in Mexico, where they talked to some Mexican women as they watched them make tortillas. The young women got enthused, adapted some of what they learned from the Mexican women in their not-entirely-for-profit venture, and then made the unfortunate mistake of talking about it to a newspaper in less-than-careful terms.

Portland burritos.

Menon pointed out that in the food industry, a ban on cultural appropriation would result in the closing or re-menuing of about 60 percent of North American restaurants, many of them very large corporate chains. Most architects, meanwhile, would quickly point out that they’d be unable to operate without cultural appropriation, and that open cultural theft has long been part of the accepted creative process in the design of residential habitats.

Americans, meanwhile, seem to have a more sanguine way of looking at cultural appropriation. They’ve tied the issue of cultural appropriation to that of cultural exchange, and suggest that it’s best treated as a continuum in which one needs to find the accurate point—and medium—of exchange. Rivka Galchen, in a recent New York Times Book Review opinion piece, argued that “To be entirely against taking anything from another culture would be to condemn everything to memoir—and of all the genres of literature, I think memoir deserves the reputation for being the least true. It’s awkward to recognize that Madame Bovary couldn’t be better written by a French housewife …[and that] it was a gay, bourgeois Jew who best portrayed the French aristocracy, not the reverse.”

Rivka Galchen.

She goes on to write that “…the difference between appropriation and exchange… would have to lie with an assessment of the value of the art itself. …the more you take, the more you have to give back—the better the work has to be. Maybe when we say it’s wrong to take something, we really mean, What you’ve given back is far too poor, too mediocre—it’s bad art.”

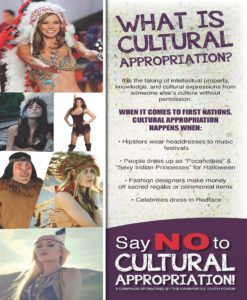

A significant part of the problem is that there is no agreed definition—and several hundred interpretations—of what cultural appropriation is and does. The OED has no definition; Wikipedia has a very tentative one: “Cultural appropriation is the adoption or use of the elements of one culture by members of another culture. …Cultural appropriation can involve the use of ideas, symbols, artifacts, or other aspects of human-made visual or non-visual culture.” It then focuses primarily on the economic implications of restricting cultural appropriation, and its possible effects on popular culture. The Urban Dictionary’s definitions are mostly dismissive, but one definition did hint at the central controversy. “Cultural Appropriation [is] taking aspects from a minority culture, for its aesthetics, without knowing the meaning behind it.” This is often controversial when the appropriated culture was exploited or oppressed by the person “borrowing”.

What is…. ?

The only way around this vagueness is to contest the nomenclature and epistemology. Both are currently hamstrung by the activists’ bureaucratic vocabulary used to build and express the issues. It is a vocabulary laden with inexact committee room euphemisms, homilies and analogies, and would be better served with either an artistic or philosophical/legal vocabulary stripped of both rhetoric or appeals to emotion. “It should be” as my longtime intellectual companion and professional sane person Stan Persky says, “‘cultural misappropriation’ not ‘cultural appropriation’ (the latter being an absurd term of disapprobation, considering that cultural appropriation is often completely appropriate… ).”

… “the thing that strikes me about the current Canadian appropriation debate,” Persky continues, “although much of it sails under a banner of literary matters, is how little it has to do with literature, or even writing. If it was a literary debate, you would think people would be arguing over the stories of the late W.P. Kinsella, or Rudy Wiebe’s novels, or even whether George Bowering’s characterization of aboriginals in Burning Water as absolutely perfect 18th c. French philosophes is appropriate or not (of course, to engage in the latter discussion with a straight face you’d have to be…utterly humourless.) … I haven’t heard much discussion of writing, citing actual writing actual people have written. Instead, there’s a great deal of politics. It’s noticeable how quickly the conversation slides from the allegedly literary to…a [finger-pointing] discussion of indigenous conditions in general that has almost nothing to do with writing.”

I can easily live with Galchen’s imposed obligation to use other cultures’ materials well and respectfully, but the political realities of this, as Persky points out, aren’t so straightforward. Such an arrangement would exonerate, for instance, Joseph Boyden’s novels because of the depth of his research and the quality of his prose. On the other hand, it does place its burden implacably on the necks of the commercially vulgar and the intellectually lazy. And because the vitality of art lies in the fine detail and not in the fog of proprietary theory and ideology that (now) surrounds it, the quality of cultural exchange at least ought to rule at most cultural intersections. And yeah, yeah, I admit that I’m a Blakean optimist about it. As Blake said, the Last Judgment—or the ultimate goal—is the overwhelming of bad art and science. Or should be, anyway, grumble, grumble…

The Background

Cultural Appropriation wasn’t initially the almost exclusively indigenous writers’ issue it has become in Canada. By the mid-1980s arguments against white, privileged writers misusing cultural materials from less privileged communities and cultures was stirring the pot at the Annual General Meetings of the Writers’ Union of Canada, an organization that then had 500 or so largely white, middle class members. In the excitement of being part of building a national culture and a distinct literature that didn’t mimic American or British literature, few writers saw anything wrong with what they were doing. Weren’t writers—especially Canadian writers– a disadvantaged minority in an American-dominated marketplace?

All the same, other voices were breaking into the conversation. Women, gay men, lesbians, black/brown, disabled and indigenous writers were voicing valid criticism of the general discourse of Canadian culture, which, like the Writers’ Union, was white and middle class, and focused on the concerns of the white middle class.

I think it was at the 1989 Writers’ Union AGM that Lenore Keeshig-Tobias, an aboriginal poet, gave a speech about cultural appropriation to a mostly-receptive plenary that the Globe and Mail subsequently published in January 1990. ( You can find the full text here. )

Lenore Keeshig-Tobias.

Keeshig-Tobias began by positing the dubious—or at least morally neutral—proposition that “stories are power”, then cited several examples of white writers’ and filmmakers’ misuse of aboriginal culture, including W.P. Kinsella’s Silas Ermineskin stories and Bruce Pittman’s film, Where the Spirit Lives. “The real problem” she said, “is that they amount to culture theft, the theft of voice. …Stories show how a people, a culture, thinks. Such wonderful offerings are seldom reproduced by outsiders”.

Few people who heard Keeshig-Tobias speak that morning saw much to argue against. Aboriginal people had been treated badly, and much of the way Canada’s white artistic community had portrayed aboriginal culture, from Archie Belaney (a.k.a. “Grey Owl”) to the present, was either condescending or simplified if not always exploitative. Aboriginal artists ought to have the same rights and opportunities as any other Canadian artist, QED. The assembled writers looked around the room and it was easy to see what they were thinking: Now what?

The Union executive and staff of the era dutifully scrambled to create the appropriate committees to increase minority membership in the Union and to otherwise “study the problem”, which is, after all, what cultural organizations untied from political movements can do in a democracy. It was the Writers’ Union, not the Marxist Writers Bureau or the Toronto Symphony Society: no workers hats and overalls, no tuxedos and evening dresses.

This kind of scrambling and dithering has now been going on for well over a quarter of a century. Progress has been made, and the number of aboriginal people in the arts has grown significantly. But the problems haven’t been solved, because most of Canada’s aboriginal peoples and most of the other minorities, at least outside the arts, remain disadvantaged. Nor has the conversation or discourse or struggle—however it is framed doesn’t seem to matter—gained much nuance, as witnessed by the current round of shouting.

Some of today’s difficulties are self-inflicted on both sides. Socially and economically comfortable people are often oblivious—and then deeply self-protective when criticized or pushed into a corner. Those who oppose cultural appropriation/exchange, meanwhile, have adopted the unhelpful (although effective) postcolonialist posture of treating everything they disagree with as a painful affront to their ethnic and racial self-esteem and find themselves, somewhat theatrically, “literally shaking with emotion” whenever a careless or foolish writer, editor or media commentator suggests that cultural appropriation might have a legitimate purpose, or wonders aloud if placing restrictions on cultural curiosity might be an abrogation of free speech and/or free enquiry.

The reality is that most of the practices that angered Keeshig-Tobias in 1989 and 1990 are more or less gone or are now practiced only by nincompoops. No competent non-aboriginal Canadian writer today would write stories with an aboriginal narrator or subject matter the way Kinsella did forty years ago. This is particularly true after the recent pillorying of Joseph Boyden, who is a competent writer who committed such a skillful appropriation of aboriginal culture that it could be argued that he has done as much as any single person in Canada has to put aboriginal writing into Canada’s cultural mainstream. Similarly, I don’t think any competent artist from any other discipline would centre their work on aboriginal myths and figures, and few non-aboriginal academics will now risk explaining aboriginal cultural values, methods and/or experience in print or in public. Where aboriginal characters make even a marginal appearance in the fiction of a non-aboriginal writer today, expect a lengthy homage to the writer’s aboriginal bona fides in the introduction or acknowledgement pages.

Similarly, heterosexual writers today don’t write much about gays, lesbians or transgender characters (and vice versa), and no Canadian writer crosses racial or even ethnic boundaries with anything more than very minor characters. Men try to avoid writing about women, and for dead certain nobody makes fun of anyone who isn’t their identical twin brother without talking to a lawyer (and I’m probably going to get yelled at because this sentence hasn’t yet mentioned the disabled). All of this is now pretty much common practice across Western countries, where the sales of literary fiction are dropping more or less universally, and, um, nobody knows why.

One of several things in what Lenore Keeshig-Tobias said that morning in 1989 that bothered me slightly was the absence of anything other than anecdotal evidence in her arguments, and the positing of uncomplimentary generalities about non-aboriginals that she treated as self-evident truths. Names weren’t named, dates and places were missing, and the argumentative logic seemed to have been left in some committee room along with the rules of evidence: you got things like “And what about the teacher who was removed from one residential school for abusing children? He was simply sent to another, more remote school.” Did I ask, What teacher? What remote school? No, I did not. Like everyone else, I was trying to figure out what came next.

The most productive approach that aboriginal writers and other artists have recently been taking to the issues of what gets written or said or pictured about them is to demand control over the means of cultural production. As a lifelong syndicalist, I think this is both admirable and strategically smart: aboriginal artists should publish their own books, make their own documentary films, produce their own television. If the rest of Canada’s writers had the same will, we might not be where we are today, with all of the country’s major book publishers U.S.-owned and operated, and with a monopoly bookseller who is happier hawking cultural bric-a-brac than selling serious books. When it comes to big-money cultural production, aboriginal artists are making it clear that it isn’t enough to have aboriginal actors involved in feature films, or that the producers hire aboriginal experts as advisors. They want to be the producers, the directors and the lead actors and the marketers. I’m unreservedly with them on this, too, and I hope they remember that what they produce has to be as good as anything else on the market, because this is a market economy, and it has recently become a market-governed culture.

All of that is good. What I’m not at all sure is good is that aboriginal cultural entrepreneurs are treating aboriginal culture as an exclusive property, and everyone else is supposed to steer clear. I recognize what this is after, and power to them for going for it, I guess. But it could backfire in a couple of different ways, none of them to anyone’s benefit. When cultural production is governed and processed by market forces—as it is now in Canada and everywhere else in the “developed” world—the most attractive property of a cultural commodity is its novelty, not its authenticity. At the moment, aboriginal stories and the spirituality underlying them are new and fresh to the market. That’ll pass, partly because the spirituality is kind of complex and slow-moving to begin with and its producer/protectors are seemingly doing whatever they can to make it exclusive and, frankly, impermeable. And it’ll pass as a hot market commodity because, well, everything does.

I’m acutely aware that indigenous and other minority Canadian writers currently operate at a peculiar disadvantage, and that it might not be the disadvantage aboriginal arts entrepreneurs think it is. Right now, every cultural institution in the country is bending over backward to please aboriginal and other minority writers and artists, whether it’s the Writers’ Union, the CBC, the public universities, or any number of federal and provincial government agencies. All these institutions deliver authentication before it can be earned, and often before it is asked for—and then, for the most part, they ignore what minority writers and artists do produce by consigning it to the artistic quicksand of “specialness”.

On the other side, a complete removal of aboriginal characters from the fiction of non-aboriginal writers could de-authenticate a significant proportion of Canadian fiction that is set in locales where aboriginal peoples are part of the general citizenship. Let me offer a personal example.

I grew up in (and still write about) Prince George, B.C., which has a significant aboriginal and Metis population. The Lheidli T’enneh band there has 415 members (as of 2015) and close to 9000 others who self-identified as aboriginal or Metis in the local 2011 census tracts.

The Last of the Lumbermen, a novel I wrote about the collapse of senior amateur hockey in the early 1990s, had both an aboriginal character and a sub-theme that spoke to aboriginal concerns. The novel was, of course, based on real world factualities, the most relevant of which was that for years, Prince George’s senior amateur team was called the Mohawks, an odd naming given that no Mohawks had ever held territory within 4000 kilometres of North Central British Columbia. The Mohawk team crest was a caricature part way between the emblems of the Chicago Blackhawks (hockey) and the Cleveland Indians (baseball), the latter of which has been under sharp criticism by Native American groups for decades. The commercial attraction of that logo (not to mention a certain poverty of historical imagination) no doubt accounted for the naming of the team, but it didn’t, in my mind and in the minds of others in Prince George, explain or excuse it. Because literature is supposed to imagine outcomes better than the real world provides and not just to imagine outcomes that are more clear than any real world outcomes ever are, my aboriginal character took the lead in getting the hockey team renamed. The real world Prince George Mohawks disbanded because someone at city hall discovered that the city had a shot at getting a Major Junior hockey franchise, which is where the money is these days.

The team name and its distasteful Chief Wahoo-style logo wasn’t crucial to the plot of the novel, but it was a real world fact and an authentic nuance I didn’t feel I should ignore, particularly since naming a Northern B.C. hockey team after an East-central North American aboriginal nation had bothered me and more than a few other locals for forty years. Cultural nuances in fiction matter, and restricting or removing the ability of any writer—aboriginal or non-aboriginal—to treat and/or acknowledge them will, aside from weakening the believability of some possibly-not-very-important works of fiction like mine, exacerbate the already-unacceptable situation in which aboriginal peoples feel disappeared from mainstream Canadian society. This isn’t trivial stuff, in other words.

Let’s return to the issue of nomenclature for a moment. For quite a while now, Canada’s aboriginal people have been tinkering with the nomenclature by which they are addressed, almost certainly to get beyond being called “Indians”, which was a wildly inaccurate term of address perpetrated by Christopher Columbus, who believed he’d arrived in India when he blundered into the Caribbean in 1492. I was uncomfortable with the initial term adopted by Canada’s aboriginal leaders to replace the old terminology. “First Nations” seemed to suggest a hierarchy of nations that became uncomfortable at the point where one tried to sort out which Canadians were then in the Fifth or Eighth or Fourteenth nation. That term and its companion vocabulary seems to have recently been abandoned in favour of “Indigenous peoples”, along with companion terms like “colonist”, “settlers” and “colonialists” for the other 96 percent of Canadians.

I confess to some personal irritation at having my ancestors, some of whom arrived in this country more than 200 years ago, branded as “colonialists.” My Scottish ancestors were poor people from the island of Tyree, forced off their lands by the Clearances at the end of the 18th century. My Irish ancestors arrived in Canada during the 1840s, refugees from the Potato Famine. All arrived destitute, none of the family legends mention them wearing pith helmets or breeches and none of them displaced aboriginal people from their land by brandishing lanyarded pistols (or anything else). They weren’t much different than the aboriginal peoples who came across the land-bridges from Asia or boated from Greenland and Northern Europe millennia ago: they were hungry, bad people had chased them from their ancestral homes, and they wanted a better life.

Whether any of them held opinions that might give offense to the racially-sensitized social entrepreneurs currently reclaiming their cultural self-esteem by pigeonholing non-aboriginals as “colonialists” or (the “nicer” terms) “colonists” or “settlers” I can’t say with any accuracy, because they’ve all been dead for a very long time. But I was raised with working class values that distinguished honesty and a willingness to work hard about three or four categories more important than whatever one’s racial or ethnic background might be, and I intend to stick with those values.

As for settlers, very few Canadian aboriginals east of the Rocky Mountains are living where their ancestors were when Europeans began to arrive in North America during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. A radial migration of aboriginal tribes to the west and north from New England took place during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The Sioux, for instance, were originally woodland aboriginals from what is now Minnesota, and were only successfully able to inhabit the American plains after the introduction, from Europe, of horses. Most of the Inuit were living south of the tree line, and several relatively small aboriginal cultures living on the northwestern edge of the Plains were pushed over the mountains by more vigorous aboriginal migrants, where they had to eke out an infinitely more precarious subsistence reliant on the rabbit/lynx cycle. A solid percentage of Canada’s indigenous people, in other words, are recent settlers too, and they might want to glance over their shoulders when they talk about “ancestral land rights”.

Maybe this is the place and time to ask the question about what indigenous peoples want to do with the 35 or so million “settlers” who live in Canada. Are the aboriginal peoples demanding the right to mistreat the settlers as badly as they were mistreated by Europeans in the past? Or do they want to empty the country of settlers so they can return to the romantic, violent past?

I’m not a supporter of nations or nationalism because I’m too well aware of just how many people nationalism is responsible for killing across my lifetime and in the decades just before I was born. I’m only willing to support Canada’s mostly civil and modest version of nationalism to the extent that it keeps us from being Americans, and because we’re not—so far—required to wave flags and go to demonstrations unless we feel like it. But I’m not willing to give up my curiosity about others in the face of anyone’s nation or national values. I’ve already agreed not to make it the focus of what I write about, but that’s intellectual courtesy, and a voluntary concession.

In a 1990s essay titled “Trotsky and the Wild Orchids”, American philosopher Richard Rorty argues that there were two cultural struggles going on in Western countries, one serious, and the other, well, if not quite frivolous then at least not of mortal consequence. The important struggle, in his mind, put together various factions of ideological fundamentalists of both the political left and right—the sort of people who demand public authority, lots of police and unrestricted individual self-determination at the same time—and pitted them against moderate liberals who believe that democracy, technology and the deliberate and systematic exercise of progressive public rights (like those that protect free speech and—in those years—still tried to redistribute income and provide social services) will, if we’re lucky, come together to increase equality of citizens before the law and decrease human suffering.

The inconsequential struggle, then (as now) was carried on mostly within public institutions between what were then called “postmodernists” like Noam Chomsky, who see Western society as an unrecoverable plutocracy bent on impoverishing all but a tiny elite, and liberal intellectuals bent on the improvement of educational opportunity, the preservation of democracy and its intellectual traditions and institutions—and, absurd as this might sound, the protection of laughter. The latter struggle, Rorty said, was “just a tiny little dispute” within the ranks of “upmarket progressives.”

Those two struggles have carried into the present, with fundamentally the same players, the same stakes and a small increase in the intensity of the hostility involved and the extremity of the positions and postures—but with changed nomenclature. In the 1990s, Rorty saw the fundamentalists as “the people who think hounding gays out of the military promotes traditional family values, as the same honest, decent, blinkered, disastrous people who voted for Hitler in 1933.” Today we recognize them as “Red America”: those Americans who recently elected Donald Trump president of the United States. In Canada, they’re most easily identified as the people who kept Stephen Harper prime minister for almost a decade, even though there are nearly as many fundamentalists on the Canadian left nowadays as there are on the right.

The current controversy in Canada over cultural appropriation is, at the limited academic and theoretical scale at which the Writers’ Union and Canada’s universities influence Canada’s culture and politics, in some respects a cynical entrepreneurial struggle for control over an unimportant corner of the cultural arena—pretty much as Richard Rorty described it twenty-five years ago, in other words. Whether it poses a significant threat to freedom of speech in any practical or global sense isn’t clear, at least not from where I sit. But it’s an unpleasant moment in Canada’s cultural evolution, mostly because of its shouting intemperance on all sides.

Yet at another level, both the cultural appropriation controversy and the global struggle between fundamentalism and moderation are a return to the darkest political simplifications of the twentieth century, which should be regarded as a century of the separation of national groups mostly perpetrated by unspeakable violence. For a country like Canada, which is conducting a courageous exercise in cultural and political inclusion, this makes it a potentially lethal intersection.

Within any functional democracy, the political and social purpose of literature and the other arts must be to make citizens understandable to one another. Translated into cultural terms, this doesn’t demand that all citizens need to be folk dancing together or even that they’re obliged to like one another. An articulate disagreement in the agora can be as culturally nourishing as a festival of solidarity, and not just because it won’t be larded with sentimentality (or sponsored by a corporation). Within Canada’s multicultural democracy, which may turn out to be a globally unique experiment in inclusive polity—and one that doesn’t have a certain ending—cultural discourse of this sort may be more crucial than we understand.

Inclusion, as either politics or culture, involves making a conscious effort to enhance the equality of the individual citizens. In a worthwhile democracy, every citizen is obliged to earn every privilege offered, and then must instantly abandon them when and if they do not support the equality of all citizens before the law and in the practice of everyday life. This is a duty not well understood, and easy to sacrifice to the more direct and tangible benefits of factional solidarity.

If you’re not sure what I’m getting at, imagine a recent immigrant from, say, Syria, trying to parse the current debate over cultural appropriation. What would they be seeing? Oh wait! Under the new cultural appropriation rules, I’m not allowed to even speculate about what a Syrian refugee would see, not permitted to depict them wondering how one minority is allowed to arrogate their spiritual imagination in the face of all the other minorities and their spiritual protocols, to turn spiritual ideas and practices into exclusive commodities and a set of privileges “others”—now lumped together as “settlers”—aren’t permitted. I’m also not permitted to suggest that the Syrians might see this as threateningly similar to what various religious factions have perpetrated on one another across the Middle East.

Back in the 1990s I was comfortably willing to give up manipulating or distorting indigenous spiritual figures or cultural relics for my own private or artistic uses—not that I’d done any manipulating or distorting in the past—because I believed in Keeshig-Tobias’ argument that it was an unearned and unjust privilege that undermined democratic equality and fairness and made the lives of indigenous peoples and their writers unnecessarily difficult. But I wasn’t prepared to go along with any codified doctrine that prevented me from exercising either my imagination or my craft, or prohibited me from even looking at the way certain kinds of people live because they’re the property of a group or group of people who are more virtuous and authentic than I was. I still feel that way. In fact, I’m going to have considerable difficulty keeping myself from making fun of the new rules, just as I would if, say, the North Korean government announced that Canadian writers are not allowed to make fun of its symbols of megalomania.

To propose that indigenous culture is a static, monolithic and eternal entity is simple foolishness. Culture is inherently dynamic: a particular expression of its time and environment, whether human or natural. We can take glamourizing snapshots so long as we acknowledge that what we have are stills from a movie that’s currently playing, and that it’s the movie that matters, not the memorials and abstractions or idealizations that we draw from it.

We also need to keep our facts straight, maybe particularly in a “national” environment, given its propensity to turn violent. To depict Canada’s aboriginal nations as if they are and/or have been a monolithic or unified cultural entity is misleading at best. North American aboriginal societies are distinct and often wildly different from one another, and were that way long before the arrival of Europeans. Since they were originally tribal nations—and tribalism is easily the most violent form of human polity that has ever been practiced—the individual indigenous political and cultural enclaves in North America were not only distinct and different from one another, they were frequently competitive and mutually hostile, including the most culturally complex of them. The west coast Haida were slavers who raided other nations up and down the west coast well before the arrival of Europeans. In the 17th century, the Iroquois used their alliance with the British to destroy and assimilate the neighbouring Huron, Erie and other aboriginal nations allied with the French well before the British defeated the French in 1759. The erasure of this history of tribal violence in contemporary aboriginal rhetoric is not an intellectual accomplishment anyone should be proud of any more than we should be proud of those histories that have ignored the presence of aboriginals. Both should be rejected as the basis for either art or politics.

Let me repeat this: Nationalism, at any scale or scope, is first and then ultimately the rhetorical obscuration of violence committed by one self-defining group against others. This is true of Canada’s history, and it was true of what indigenous people called, until recently, “First Nations”. Nationalism is a form of mass insanity, one that always excludes some people in order to elevate others.

The Character Bank

The day after Keeshig-Tobias delivered her speech in 1989, a number of practical-minded members of the Writers’ Union, all of them adult fiction writers, recognized that it would be difficult to write engaging stories with their gaze permanently fixed on their own pale, middle class navels, and that a rigorous prohibition of cultural curiosity would effectively restrict Canadian fiction to stories about tiny isolated hinterland communities that had lost touch with the remainder of the country around the time of the First World War.

If writers were no longer to be permitted to deploy characters in their fiction who were “other” than themselves and their ethnic or racial group, the fiction writers reasoned, then the Writers’ Union ought to organize and regulate a “character bank” of accurately and respectfully defined characters, each one created by an individual Canadian writer—or at least a Writers’ Union member—based on what he or she could discern of themselves while gazing intently into his or her navel. The character bank, the fiction writers suggested, would charge a nominal fee for the use of a licensed character, which would come with a full rendering of physical and mental attributes: likes, dislikes, preferred and prohibited activities, prejudices and, hopefully, endearing but developable quirks and eccentricities. It would be the duty of the character-creating writer to clear his character as acceptable to his or her ethnic, racial or preferential life-style group, should any of those be a governing trait. Fees collected for the use of the character would go back to its creator, with an ascending schedule of fines exacted against writers who, having rented a character, forced that character to commit culturally prohibited or hurtful behaviors, or otherwise operate beyond its comfort zone.

There were other problems to be worked out. The character bank, given the ethnic racial and class profile of the Union membership in the 1990s, would have initially resulted in an overly large number of stories about elderly white people sleeping on couches, or toward morally-aggressive adventure stories in which children’s authors would pursue their unending quest for properly-fitting polyester leisure suits. On the positive side, it would, in the long term, have given energy to the Union’s drive to create a more ethnically and racially diverse membership by providing income to minority writers, whose deposited characters would likely have experienced plenty of business as Canada’s multicultural mosaic deepened in range and diversity.

Were the writers who proposed the character bank serious? Yes, of course they were, in the same way that Jonathan Swift was serious in 1729 when he suggested, in A Modest Proposal, that the answer to Irish poverty was to eat the children of Ireland’s poor. They were also making fun of bureaucracy in general, and perhaps they were critiquing the Writers’ Union for thinking it could be an arena for meaningful social change when, at best, it could only be the forum for talking about it.

But whether those fiction writers who dreamed up the character bank were serious or not, I don’t think the Union’s executive at the time gave sufficient consideration to implementing their idea, which admittedly would have been complicated to set up and more complicated still to regulate and administer. Whatever they believed, the absence of that character bank in 2017, given the de facto prohibition of cultural exchange that now appears to be on the horizon, might explain the present emaciated character, so to speak, of Canadian fiction and the marginal relevance of the Writers’ Union.

Perhaps, instead of the epidemic of forelock tugging and editorial self-decapitation we are currently witnessing, the Writers’ Union might want to dust off the idea of the character bank. Such an institution might help to preserve—or reconstitute—the self-esteem of some of Canada’s writers, and, possibly more important, it might just provide the perfect framework for a Canadian cultural producers’ code of appropriate conduct, along with a schedule of artistic responsibilities. Such a code is much more likely to provide level ground for all Canada’s writers than a bullying set of reparational equity rules and policies designed to make anyone unable to find the shelter of an approved minority into a guilty shithead. The Union, should, at very least, strike a committee in which all the Unions’ writers are proportionally represented down to the most unique minority that can be unearthed, and set it to investigate the feasibility of producing the code. Or maybe, since the character bank is clearly necessary and perfect in its logic and virtue (not to mention a lot more fun than bickering endlessly over what and who we’re allowed to imagine and write about), the committee could just devise the character-creation forms needed and fill them out.

* * *

I hope my description of the character bank hasn’t made any readers wonder if maybe I’m not a serious person. I am a completely serious person, as always, and here’s what I’m serious about: I’m seriously disturbed by the growing proprietary intolerance in most sectors of Canada’s cultural community and by the evident willingness of cultural workers to exclude others from their domain over issues of manners, rhetoric, ideology and physical appearance. I’m seriously troubled by the general rebirth and continued growth of exclusionary nations and nationalism, here in Canada and everywhere else, and I’m seriously angry about the disappearance of playfulness and fun and the increasingly intolerant attacks on irony.

The corrupting power of social media, meanwhile, is simply frightening. The quality of discourse and commentary on Facebook most often resembles that of those grade eleven girls who stood around the entrance to the women’s washroom making snide remarks about whoever passed by: boys, teachers, other girls. They heap abuse on anyone who doesn’t want what they think is fashionable. And when it’s not those grade eleven girls it has sunk lower, and we find ourselves listening to the grade ten boys smoking cigarettes behind the gym and cursing out everyone and everything but their mirror images. Or (worst of all) it’s the hall monitors, the playground supervisors and the rest of the growing army of security personnel insisting that everyone be nice, positive, and supportive so they can get the hell away from the tilted fields, find a place to get drunk and snarly—and let their own demons out.

Twitter is no better. At its best it is little more than intellectual or social or political spearfishing, and at its worst, a swarm of hornets.

Choose your poison, because social media works, and it strengthens all the political nations, mini-nations and fascistas that undermine democracy.

Finally, what bothers me most is that the new iteration of cultural appropriation is a direct assault on our not-quite-god-given but politically-and-artistically-crucial right—and cultural duty—to be irreverent and contrary in the face of received wisdom and its authorities. I’m not joking about the importance of this right, and neither was George Orwell when he said that “If liberty means anything at all, it means the right to tell people what they do not want to hear.”

Smart-asses are the first thing that every totalitarian dictatorship in human history has gone after the moment it achieves power. The primary safeguard to most of Western civilization’s democratic institutions and individual rights really is the exercising of the right to make irreverent, smart-ass remarks. If and when that right is protected, then all the other rights we have—freedom of speech, of thought, of assembly—are in no danger. And for the first time in my long lifetime, that right is under attack from all sides.

So let me summarize: the physical and political conditions under which indigenous people in Canada live are really important. They haven’t been treated either fairly or equally, they haven’t had the opportunities the rest of us take for granted, and that needs to change. But the issue of cultural appropriation, by comparison, isn’t very important. It isn’t trivial, but right now it is so poorly conceptualized that its avid pursuit is making a bigger mess than we’ve already got.

You could say, for instance, that Brokeback Mountain is a perfect example of cultural appropriation: it’s a story about gay teenage cowboys written by a woman (Annie Proulx), that was turned into a screenplay written by a middle-aged heterosexual Texan (Larry McMurtry) and his writing partner Dianna Ossana, and then made into a movie directed by a Taiwanese heterosexual (Ang Lee), with lead protagonists performed by, as far as we know, heterosexual actors ten to twenty years older than Proulx’s teenagers. Should the story and screenplay have been written by gay men, the movie directed by a gay man, and the actors played by gay sheep-herding teenage cowboys? And what about our sacred Canadian landscape being appropriated to play the original story’s Wyoming?

I hope this example demonstrates that the problem of cultural appropriation, when it comes to the art part of things, is more complicated than the culture-of-outrage folks imagine it to be. Yes, of course, people who are women, gay, trans, mad, Indian-Pakistani-Bangladeshi, plumbers, dockworkers, miners, one-legged migraine sufferers, victims of anything-and-everything and the merely easily offended ought to be able to get their writing published, if the writing is any good.

The rest of it, really, is just business. You bully and push, and you bet, you steal, you grab what you can and run with it. It’s why we invented art in the first place, and now it’s trying to kick in those doors.

8000 words, June 29, 2017 (an extended version of this essay was published as a joint publication of David Mason books and www.dooneyscafe.com in 2019)