Cuckoo Coup

Democracy vs. Autocracy in a Post-Truth Era

More than half a year after the apparent coup attempt at the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021, the New York Times decided, for inexplicable reasons (well, inexplicable to me at least), to run an op-ed by Christopher Caldwell denying that the violent events at the U.S. Congress that day were part of a coup attempt, an insurrection, an assault on democracy, or anything more than “a political protest that got out of control.” (Christopher Caldwell, “What if There Wasn’t a Coup Plot, General Milley?”, New York Times, July 28, 2021.)

Jan. 6 at the Capitol

To make sure we’re all on the same page, before unpacking Caldwell’s argument, let’s first define our terms and the contextual parameters. For starters, there’s Wikipedia’s rough definition of a coup as “the seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal, unconstitutional seizure of power by a political faction, the military, or a dictator” (Wikipedia, “Coup d’etat”). Later, we can determine what coups require in terms of legal and/or practical elements, such as “intent” or “competence.” Before determining whether there was a coup attempt or not, I suppose we should ask, Does it matter if former president Donald Trump and his followers were really intent on subverting a standard ritual of democracy — namely, the verification by Congress of the 2020 presidential election — and thus seeking to overthrow the election, and the government itself? What if it was no more, to recall an old song title, than a “cu-cu-rru-cu-cu, paloma,” the cooing of the mourning dove, rather than a more ominous “cuckoo-rue-coup-coup”?* (*The slightly strained puns here refer to Tomas Mendez’s 1954 song “Cucurrucucu Paloma,” an onomatopeic title that echoes the characteristic call of the paloma.)

That’s the question that CNN’s chief media correspondent Brian Stelter, host of Reliable Sources, addressed in the wake of Caldwell’s opinion piece and fresh evidence of the ex-president’s direct attempt to importune the quasi-autonomous Department of Justice to affirm Trump’s claims of a corrupt election. “Drip, drip, drip…” said Stelter, referring to the way bits of information about Jan. 6 and its backstory were gradually coming into view. “The details of Donald Trump’s attempted coup last winter are dripping out,” Stelter added, apparently not in any doubt about how to characterise the events.

“Why is this newsworthy now?” the media critic asked. “Why is this lead-worthy, six months later? Because most people don’t know how close the country came [to a coup], and because someone might try to do it again… It’s one of the biggest political stories of our lifetime. But it’s in the past. So it may not be getting enough attention and enough play…. Was it a shambolic coup? Sure. Was it pathetic, was it not well thought-out? Sure. But still a coup attempt,” concluded Stelter. (Brian Stelter, lead item, Reliable Sources, CNN, August 8, 2021.)

Jan. 6 at the Capitol.

Which is to say, Yes, it matters whether it was a coup attempt or merely an out-of-control political protest. One is a mundane, if disorderly bit of civic unpleasantness; the other is an assault on the very institutions and conventions of democracy, however flawed that form of political life is in the present United States. Further, determining the nature of the assault is all the more relevant if, as many suggest, that coup attempt is still in progress. (More on the latter in due course.)

Christopher Caldwell.

For readers unfamiliar with op-ed writer Christopher Caldwell, apart from his view that the coup attempt wasn’t a coup attempt: he’s a former editor of the now-defunct Weekly Standard (a pro-Republican Party, but anti-Trump newspaper); a senior fellow at the conservative Claremont Institute, as well as a contributing editor to the right-wing think-tank’s Claremont Review of Books; and the author of, most recently, The Age of Entitlement: America Since the Sixties (2020). This is not the place to fully canvass the arguments of that book but, again, for those unfamiliar with Caldwell’s work, a passing comment is pertinent to the issue explored in this essay, namely, what kind of coup did Trump attempt to incite?

In Age of Entitlement, Caldwell argues that the great civil rights movement of a half-century ago (codified in the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the subsequent 1965 Voting Rights Act) usurped the U.S. Constitution, with deeply negative consequences for the country.

One interviewer, Sean Illing, said to Caldwell, “You write that white Americans ‘fell asleep thinking of themselves as the people who had built this country and woke up to find themselves occupying the bottom rung of an official hierarchy of races.’ People will read that, fairly or not,” Illing gingerly continued, “as the cry of a reactionary, someone who doesn’t recognize the country anymore and hates what it’s become.” (See Sean Illing’s interview with Caldwell, “Christopher Caldwell’s big idea: The civil rights revolution was a mistake,” Vox, Feb. 19, 2020.)

To which Caldwell replied, “I don’t think of myself as a reactionary, but one of the unintended consequences of civil rights was to create a white consciousness… as long as civil rights law focused on segregation, it was both comprehensible and it had some boundaries which I think kept the country calm. But as it spread, you started having coalitions based on rights. And the two parties evolved around this coalition-building. So you have these rights-based coalitions that unite blacks, immigrants, the handicapped, women, gays, transgender people, everyone who benefits from these new protections. But as that happens… a segment of the population gets cut out from the conversation, and that segment becomes its own coalition, which is principally white Americans.”

Caldwell’s curious formulation defines “principally white Americans” as male, heterosexual, native-born, perhaps getting on in age but still able-bodied, and of course, White (with a capital “W” according to the current style-sheets of various newsrooms). “White Americans,” by this definition, in addition to discarding all people of color, apparently doesn’t include women, gays, immigrants, the disabled or transgender people, even though there are millions of American citizens that are “white”-skinned, who are women, gays, foreign-born, disabled, and transgender.

If that isn’t off-kilter enough, it’s also the case that “white consciousness,” pace Caldwell’s suggestion that it more or less sprang into existence during the mid-20th century civil rights era, is hardly a recent phenomenon. In fact, it predates the civil rights movement by decades, and even centuries, depending on your historical perspective, and it described itself as late as the Great Depression of the 1930s, blatantly enough, as “White Supremacy.” So, let’s not pretend that “white” whatever (“consciousness” or “supremacy”) is just recent pushback against excesses of liberal politics. (See Ira Katznelson, Fear Itself: The New Deal and the Origins of Our Time (2013).) I think that provides enough of an idea of what’s on Caldwell’s mind, but if you need more, it’s available (see the review of The Age of Entitlement by Jonathan Rauch, “Did the Civil Rights Movement Go Wrong?”, New York Times, Jan. 17, 2020).

2.

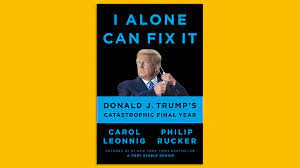

The immediate impetus for Caldwell’s assurance that the Jan. 6 riot in Washington, D.C. was merely a bit of “mayhem on behalf of what had started as a legitimate political position” was the appearance in spring 2021 of the first crop of books about the conclusion of Donald Trump’s presidency. The most significant of these early drafts of history are Michael Wolff’s Landslide: The Final Days of the Trump Presidency; the more in-depth chronicle provided by Washington Post reporters Carol Leonnig and Philip Rucker in their I Alone Can Fix It: Donald J. Trump’s Catastrophic Final Year; and Wall Street Journal White House reporter Michael Bender’s Frankly, We Did Win This Election: The Inside Story of How Trump Lost. The latter, uniquely, spends considerable time tracking Trump devotees who travel from rally to rally, camping out all night to get front-row seats, organizing themselves into a nomad community that’s a sort of cross between a cult and a 1950s canasta club. They’re among the most intriguing political actors in the current scene, not so much for their ideas but for the more than 30% demographic presence they represent. I find myself pondering them far more than Trump.

“I Alone Can Fix It.”

All three of these forays into contemporary history, with their eponymous Trump quotes, can be unreservedly recommended to readers as engaging, informative, and helpful in answering the question at hand. Finally, as of autumn 2021, Bob Woodward and Robert Costa’s Peril (the conclusion of Woodward’s trilogy on Trump’s term in office) can be added to this burgeoning sub-genre.

Gen. Mark Milley.

It’s in the Leonnig and Rucker volume that Caldwell encounters the U.S.’s top military man, General Mark Milley, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, who openly worried to his aides that Trump wanted to make illicit use of the U.S. military as part of the defeated president’s bid to overturn the results of the 2020 election. Caldwell’s challenge to Milley’s fears of a coup attempt is what led to the headline, “What if There Wasn’t a Coup Plot, General Milley?” Milley, it turned out, often thought about the parallels between Trump and early 20th century fascism. “This is a Reichstag moment,” he told those around him at one point, referring to the 1933 burning of the German parliament, which Hitler used as a rationale for seizing total power. “The gospel of the Fuhrer,” the American general murmured darkly. We’ll get to the Nazis and present-day proto-fascists eventually, but first let’s address the political situation that Caldwell declared to be “legitimate.”

The “legitimate political position” to which Caldwell is referring is Trump’s claim that the election rules were somehow “rigged,” which then morphs into the further assertion (believed by hordes of the former president’s followers) that the election was “stolen” from him through massive voter fraud. This “legitimate political position” is more commonly known among Trump’s opponents and the liberal media as the “Big Lie,” given that not a scintilla of credible evidence has been produced in support of it, that various aspects of the claim have been ruled illegitimate by more than 50 U.S. courts (including the Supreme Court of the United States), and that nonetheless the ex-president has insisted on this delusional account of a stolen election ever since the 2020 contest that he lost, right up to and including the present moment.

Although it hardly needs to be said, I should note for the record that Trump is not a unique phenomenon, strongman, potential dictator. The U.S. has had many politically extreme figures in the 20th and 21st centuries from Senators Joe McCarthy and Barry Goldwater, to former president Richard Nixon and various other transiently popular demogogues. If there’s anything new here, it’s the political conjuncture marked by polarization, “post-truth” ideologies, and a U.S. in likely political decline

Here’s a slightly extended examination of the argument Caldwell makes in his coup-denial column. The foundation of his case rests upon the notion that there was possibly something wrong with the conduct of the 2020 U.S. presidential election. “Republicans had — and still have — legitimate grievances about how the last election was run,” Caldwell contentiously asserts. “Pandemic conditions produced an electoral system more favorable to Democrats. Without the Covid-era advantage of expanded mail-in voting, Democrats might well have lost more elections at every level, including the presidential,” he adds. At which point, if you’re inclined to say, “Hey, wait a minute,” you’re picking up on the cuckoo strain in Caldwell’s argument.

Ballot drop box.

Remember, the problem in the middle of a pandemic election was how to ensure that citizens could cast their votes. While seven states already employed “automatic mail-in ballot systems” (thus the mail-in ballot was hardly an untested novelty), many other states expanded mail-in voting for the 2020 election to reduce the danger of catching Covid while voting in person. Various other accomodations were made, from providing adequate boxes to drop off mail-in ballots, to drive-through voting “booths,” to extended polling hours. While there were squabbles about marginal issues, the election rules were neither controversial nor unfair. The point is, the increased voting opportunities were available to everybody. Nobody was disadvantaged. The whole idea of a democratic election is to maximise the opportunity for all eligible voters to vote.

Caldwell’s slippery claim that the voting rules “advantaged” Democrats is false in the most important sense of that term. It’s true that more Democrats (and independents) availed themselves of the mail-in voting method, but Republicans could have done the same. Nothing was stopping them (except perhaps the advice of their leader). The claim that the whole process was rigged to benefit Democrats is the sleight of hand in Caldwell’s argument that you’re not supposed to notice. As a Washington Post editorial put it, “Republicans increasingly embraced the anti-democratic fiction that voter access, particularly for the disadvantaged, is synonymous with voter fraud.” (Editorial, “The John Lewis Act would restore key voting protections,” Washington Post, Sept. 7, 2021.)

Having planted the suspicion that the rules were constructed to “advantage” the Democrats, the further suggestion of widespread voter fraud (made by Trump) is easily enough elided into the “rigged” rules claim. Caldwell is silent when it comes to recognising that the actual election results don’t support his claim: while Trump was defeated, Republicans down-ballot, despite the alleged Democratic “advantage,” were quite successful in picking up House seats, as well as prevailing in state legislative contests across the country. Indeed, apart from the presidential contest, it would not be incorrect to say that Republicans fought the 2020 elections to a draw. An expected “Blue Wave” Democratic landslide simply didn’t occur, despite the Democrats retaining control of the House, ultimately securing a 50-50 split in the Senate, and winning the White House. I take it that Caldwell’s omission of the facts here is not accidental.

Once Caldwell has posited as a fact that there was something wrong with the 2020 election rules, and that protests against the election results were a “perfectly rational proposition,” he is prepared to be urbane and reasonable about the whole process. “Whether the country ought now to return to pre-Covid voting rules is a legitimate matter for debate,” Caldwell smoothly allows. He is also willing to concede that “Mr. Trump’s conspiracy thinking” about the election was a problem, in that it provided an organizing focus for a range of inchoate resentments and scattered thoughts “among supporters of the perfectly rational proposition that election laws had been improperly altered to favor Democrats.” The accomodating Caldwell parenthetically points out that “(To say that the proposition is rational is not to say that it is incontestably correct).” One can almost hear the dulcet tones of the chaps at the gentleman’s club “discussing” in good faith the nuances of a politely held contested position.

Trump speech Jan. 6

Caldwell is also quick to admit that those “who held this idea in a temperate way” soon gave way to others. The “adults in the room” were replaced by “the crazies,” as the books about Trump’s final days in office dub them – conspiracy theorists, shyster lawyers, grifters trading loyalty for future considerations, and the maddened crowd. By January 6, in Caldwell’s view, “the grounds for skepticism about the election were unchanged. But they were being advanced by an infuriated and highly unrepresentative hard core,” a mob of a few thousand people who had been inflamed by a “we must fight” speech delivered moments before by Trump himself, who urged the crowd to march down to the Capitol where the Electoral College verification vote was taking place. Trump’s “fighting words” were echoed by a half-dozen of the president’s henchmen. (“Trial by combat!” cried the president’s personal lawyer, former New York mayor Rudy Giuliani, having watched too many episodes of Game of Thrones, a television series where this phrase becomes a battlecry).

Trump supporters clash with police and security forces as they push barricades to storm the US Capitol in Washington D.C on January 6, 2021.

Nonetheless, says Caldwell, “The result was not a coup. It was, instead, mayhem on behalf of what had started as a legitimate political position. Such mixtures of the defensible and indefensible occur in democracies more often than we care to admit. The question is whom we trust to untangle such ambiguities when they arise.”

“Were we really that close to a coup?” Caldwell asks, in a clearly dubious tone of voice. “The most dramatic and disruptive episode of Mr. Trump’s resistance to the election was Jan. 6, and that day’s events are ambiguous.” Ambiguous? Caldwell admits that “on the one hand, it is hard to think of a more serious assault on democracy than a violent entry into a nation’s capitol to reverse the election of its chief executive. Five people died. Chanting protesters urged the hanging of Vice President Mike Pence, who had refused Mr. Trump’s call that he reject certain electoral votes cast for Joe Biden.” That doesn’t sound much like ambiguity to me.

But Caldwell thinks there’s an alternative perspective (or perhaps an alternative reality): “On the other hand, Jan. 6 was something familiar: a political protest that got out of control. Contesting the fairness of an election, rightly or wrongly, is not absurd grounds for a public assembly. For a newly defeated president to call an election a ‘steal’ is certainly irresponsible. But for a group of citizens to use the term was merely hyperbolic… Nor did the eventual violence necessarily discredit the demonstrators’ cause…The stability of the republic never truly seemed at risk.”

At this point, Caldwell calls on Michael Wolff (in his book Landslide) to attest to the ex-president’s incompetence as a coup instigator. Wolff writes, “Beyond [Trump’s] immediate desires and pronouncements, there was no ability — or structure, or chain of command, or procedures, or expertise, or actual person to call — to make anything happen.” Caldwell adds, “Mr. Trump ended his presidency as unfamiliar with its powers as with its responsibilities. That is, in a way, reassuring.”

That’s why General Milley’s worries about a coup were irrelevant. “General Milley had no direct evidence of a coup plot,” Caldwell claims. But then, seemingly unaware that he’s rebutting his own argument, Caldwell lays out some of the litany of indirect evidence that alerted Milley to the danger. As Caldwell puts it, “In the days after Mr. Trump’s electoral defeat, as the president filled top military and intelligence posts with people the general considered loyal mediocrities, General Milley got nervous.” And should we not wonder why Milley got “nervous”?

Caldwell here references Leonnig and Rucker’s I Alone Can Fix It to get Milley’s remarks on the record They may try, Milley said of Trump and his enablers, but they would not succeed with any kind of plot, he told his aides. Caldwell then cites the rest of Milley’s statement: “You can’t do this without the military. You can’t do this without the C.I.A. and the F.B.I. We’re the guys with the guns.”

Caldwell says, “While some might greet such comments with relief, General Milley’s musings should give us pause… If there was not a coup underway, then General Milley’s comments may be cause more for worry than for relief.” So, the final irony of Caldwell’s narrative is that it’s not Trump and his mob we should worry about, but the possibility that Milley’s alleged misinterpretation of the situation is itself good reason to worry about a coup – not one incited by Trump, but a military coup, presumably led by Milley and his institutional counterparts. Talk about a too-clever-by-half “Oh, what a tangled web we weave / when first we practice to deceive”!

As we’ll soon see, what Caldwell omits from his account of Milley’s activities during the height of the coup threat is indispensable to understanding the general’s apprehensions. Those activities included, as Leonnig and Rucker document, not only the Chairman’s direct encounters with a frequently enraged Commander-in-Chief, but also Milley’s daily private consultations with a group of high-ranking White House and Pentagon officials. Among them were Defense Secretary Mark Esper, Attorney-General Bill Barr, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, and even the president’s chief of staff, Mark Meadows, as well as the urgent calls Milley fielded from senior Congressional leaders, in order to discuss Trump’s attempts to reverse the election results and to forestall their mutually-shared most ominous fear, namely, a coup attempt. In sum, Milley was hardly alone in bracing himself for the possibility of an attempted seizure of power.

3.

Washington Post columnist Max Boot, himself a moderate conservative, was among those who promptly began to unravel the argument promoted by people like Caldwell and, equally important, to pin down its function in the debate. Boot begins by reiterating the unique character of the events upon which the story rests. “Something uprecedented occurred after the Nov. 3 election,” he says. “An incumbent president refused to recognize the results and, in fact, tried to overturn them. That effort culminated in another unprecedented event on Jan. 6: The president instigated a mob attack on the U.S. Capitol in the hope of stopping the vote certification.” (Max Boot, “Yes, Trump tried to stage a coup. By denying it, the right is laying the groundwork for another one,” Washington Post, August 4, 2021.)

WaPo columnist Max Boot.

Boot says that Republicans are forced to make excuses for what happened on Jan. 6 in order to continue to support the former president. The attempt “to minimize the horror of that day… comes in two varieties: hard and soft.” The hard or extreme version of the narrative “is what you hear from the party’s far right,” says Boot – “loony rabble-rousers” such as Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-Ga.), the promoter of bizarre “QAnon” conspiracy theories about how the U.S. government is manipulated by various dark forces. There are myriad others, from rightwing radio and TV hosts, former White House appointees, private strategists and freelance entrepreneurs, all the way up to the former president himself. As Boot says, this exculpatory version of events, however improbable, “has gained disturbingly wide acceptance on the right,” including from a majority of Trump’s hard core base, who see the Jan. 6 riot as a defense of “freedom,” and an expression of “patriotism.” They’re fond of describing the several hundred people charged for their participation in the riot as “political prisoners.”

The hard version, Boot says, “is so obviously nuts that more sophisticated apologists for Trump’s crimes cannot repeat the new party line with a straight face. Hence, a softer version of 1/6 minimization has taken hold among some right-wing intellectuals.” Enter Christopher Caldwell. Boot notes that Caldwell’s strategy is to downplay General Milley’s concerns. “Instead of thanking the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff for defending democracy, Caldwell suggested there was nothing to worry about,” says Boot, and then recites the litany of Caldwell’s minimizing claims: “Milley had no direct evidence of a coup plot”; there were legitimate Republican grievances “about how the last election was run”; what most people saw as an insurrectonary riot was merely “a political protest that got out of control”; and, finally, there’s the assertion that there was always a stable republic that “never truly seemed at risk.” “So, clearly it was no big deal,” is Caldwell’s insinuation, says columnist Boot.

He neatly characterizes Caldwell’s argument as no more than “excuse-making for extremism – and sophistry of a high order. It is possible to see the events of Jan. 6 as merely a ‘political protest that got out of control’ only if you willfully ignore everything that happened in the months beforehand.” Boot then reprises the series of red flag incidents that laid “the groundwork to overturn the election results.” It’s the narrative that scrupulously connects the dots, which is found in all the Trump books referred to above.

“Trump’s incitement of the Jan. 6 mob,” Boot concludes, “was only the culmination of what was, yes, a coup attempt. It failed only because so many Republican officeholders and the nation’s top military officers refused to do Trump’s bidding. But we can’t count on similar forbearance in the future given the ongoing purge from the GOP of all politicians who put loyalty to the Constitution above loyalty to Trump.” Further, “The effort to minimize and normalize what happened on Jan. 6, in both its hard and soft variants, is laying the groundwork for a potentially more successful coup attempt the next time around.” Someone like Caldwell, Boot suggests, is in that sense more dangerous than the “looney rabble-rousers.” The latter appeal only to the hardcore base, whereas Caldwell offers a seemingly plausible defence of the coup attempt intended to engage moderate conservatives and centrist liberals, the very people whose votes stymied Trump’s bid to remain in power. “Rest assured,” Boot warns, “even if the worst happens, there will be plenty of intellectuals happy to rationalize the end of our democracy.”

In conjuring up that rationalization, Caldwell, as noted, turns to Leonnig and Rucker’s I Alone Can Fix It to track General Mark Milley’s growing anxieties about Trump’s post-election maneuvers. If ever the old chestnut about wildly divergent interpretations of the same volume deserves to be invoked, this is it: Caldwell and I are not reading the same book when we draw our conclusions from I Alone Can Fix It. (All quoted material in this and the following section below, except where otherwise noted, is from Leonnig and Rucker’s book.)

Although one reviewer complained that I Alone reads like “300 daily newspaper articles taped together,” its chronicle-like quality, and its page-turning narrative drive are what make it the best of the four most prominent books about the Trump coup attempt so far. Simply putting together the day-by-day chronicle is particularly helpful, since we’re prone to forget the exact sequence of events, which is what reveals the pattern that adds up to a failed coup attempt. It also lets me put aside Caldwell as a stalking horse, along with all the similar apologists promoting “excuse-making for extremism — and sophistry of a high order” (as Boot has it), and turn directly to what engaged General Milley’s attention.

Milley became concerned about two separate but related possible “misuses” of the military. One was the danger of the direct use of active duty military troops to constrain widespread U.S. protests against police violence, especially violence primarily directed against Black people. The alleged need to “restore” order in the face of such protests might also require or justify the imposition of some form of martial law carried out by active duty troops, along with the suspension of normal electoral processes.

The other potential misuse was the possibility of President Trump in his last days in office ordering the use of the miltary to launch a pre-emptive strike on a U.S. adversary (perhaps Iran or China). The initiation of such a war would provide either a distraction from Trump’s election loss, or even cover for the president to invoke some form of martial law that would leave him in office, despite the electoral defeat. (This is sometimes known as a “Wag the Dog” scenario, in reference to a 1997 satiric film in which the plot revolves around such a ploy to distract public attention from a politics-related sex scandal.) In one sense, such possibilities are far-fetched, but so are all attempts at a coup, until, of course, the coup succeeds. The more pertinent issue is, was there sufficient evidence of an effort to overthrow and reverse the results of the 2020 presidential election to make such premonitions plausible?

It’s useful to remember the broader context in which General Milley’s apprehensions developed. In mid-2020, the U.S. was dealing with multiple crises. First, and most obvious was the American experience of the coronavirus pandemic, a crisis exacerbated by Trump’s attempt to downplay the danger of the virus. Second, there was simultaneously the related deep economic recession resulting from the lockdown of businesses due to Covid, again a situation aggravated by the president’s insistence on widespread premature business openings in order to create the impression of a recovering economy.

Dr. Deborah Birx.

Both the underplaying of the pandemic and the rush to reopen collided to make the medical emergency worse, resulting in the unnecessary deaths of many people. Dr. Deborah Birx, one of the leaders of the White House’s coronavirus response team, who testified to a House subcommittee on October 12-13, 2021, estimated there were as many as 130,000 preventable deaths, if the Trump administration had not been so “distracted” by political considerations. Third, all of this was complicated by the more than year-long political campaign for the 2020 presidential and other elections, again colored by the president’s eccentric behavior in relation to these political contests. (Dan Diamond, “Election ‘distracted’ Trump team from pandemic response, Birx tells Congress, saying more than 130,000 people died unnecessarily,” Washington Post, Oct. 26, 2021.)

George Floyd.

Finally, on May 25, 2020, there was the shocking murder of George Floyd, an unarmed Black resident of Minneapolis, Minnesota, who had been stopped by police on suspicion of attempting to pass a $20 counterfeit bill at a neighborhood grocery store. Floyd died during his arrest when a white police officer pressed his knee against Floyd’s neck for over nine minutes until the 46-year-old man, handcuffed and lying face down on the street, stopped breathing.

Although many unarmed Black citizens had been killed by white police in preceeding years (most often by shooting), this murder was especially cruel, and it so happened that the entire incident was recorded on smartphone video by a bystander. That video immedately went “viral,” via social and news media, thus averting potential contested descriptions of the murder, and it also provided the basis for laying murder changes against the officer involved, a rare instance of the state enforcing accountability on police behavior. The murder ignited the most extensive expression of anger and mass public marches in years (displays of public outrage not seen since the 2014 police killing of a young, unarmed Black man, Michael Brown, in Ferguson, Missouri). There were demonstrations in dozens of U.S. cities by millions of protesters of all ethnicities. Although there were some episodes of looting and violent vandalism, one of the notable features of these mass marches was their peaceful, non-violent character. (See Sanya Mansoor, “93 per cent of Black Lives Matter Protests Have Been Peaceful, New Report Finds,” Time, Sept. 5, 2020, a claim vigorously denied by conservative politicians and news outlets.)

Perhaps the key incident that triggered General Mark Milley’s attention was a brutal attack on peaceful protesters a few days after George Floyd’s murder, on June 1, 2020 in Lafayette Park, just across the street from the White House in Washington, D.C. The president, rather than seeking to remedy police misbehavior, was infuriated by the nation-wide demonstrations, regarding them as a near-insurrectionary assault on the country by Black Lives Matter militants, shadowy “antifa” (anti-fascist) agitators, and assorted left-wing radicals. Trump reacted with an assertion of the need for a counter-insurgency level of “law and order,” and warned that he might invoke the Insurrection Act, which permits the president to utilize military forces to quell such an insurrection. (See Wikipedia, “Insurrection Act of 1807.”)

Trump’s photo-op.

In politically tense Washington, Trump decided that he and his team would walk from the White House across Lafayette Park to hold an authority-confirming photo-op at nearby St. John’s Episcopal Church (which had recently been damaged by arsonists). First, however, police were ordered to clear peaceful demonstrators from the park and adjoining streets, and they did so, using tear gas, stun grenades and other non-lethal munitions, along with horse-mounted officers, National Guard backup, and the panoply of methods more usually employed against armed, violent adversaries. That day, General Milley donned combat fatigues, as was customary, to visit National Guard troops along with Secretary of Defense Mark Esper. At the last minute, Milley, in the company of Esper, was unwittingly drawn into the president’s entourage as Trump led the walk across the now-cleared park to St. John’s Church where he stood before the building (without entering) and held up a Bible as the media took advantage of the photo-op.

Gen. Milley at Trump photo-op.

For Milley and Esper, both Trump appointees, this was a turning point of sorts. Upon realising that he had been suckered into a political occasion solely designed to display the president’s engagement and piety, Milley promptly exited the scene, but not before both he, in battle attire, and Esper had been captured by press visuals, showing them supportively attending the commander-in-chief. The photo-op turned out to be a flop, with critics easily seeing through Trump’s insincerity and opportunism, but for Milley and Esper, it was a disturbing incident. Both felt compelled to speak out.

After two days of consultations with a broad array of colleagues, Esper appeared at the Department of Defense press briefing room on the morning of June 3. In addition to condolences to the family and friends of George Floyd, and recognition of the Constitutional right to protest systemic racism, Esper expressed his view that, as Leonnig and Rucker put it, “he had always felt the National Guard… was better suited to supporting police in times of civil unrest – and, importantly, that he did not support invoking the Insurrection Act,” the action being advocated by the president.

“The option to use active-duty forces in a law enforcement role should only be used as a matter of last resort, and only in the most urgent and dire of situations,” said Esper. “We are not in one of those situations now.” For good measure, Esper indicated that he hadn’t known in advance that Trump’s walk was being staged as a presidential photo op, nor did he know that police had earlier used force to clear protesters. The president watched his Defense Secretary’s statement on a White House TV, and his resultant rage would be expressed in a series of meetings, shouting matches, and unrestrained temper tantrums over the following days. Nor would Trump forget Esper’s display of “disloyalty.”

Milley was also chagrined by having, however unintentionally, participated in an event that blurred the long standing principle of the constitutional precedence of civil society and civilian control of the military, and the separation of that military from partisan political involvement, one of the pillars of a democratic polity. Like Esper, Milley also felt obliged to speak out. He used the occasion of a scheduled speech a week later, on June 10, delivered to the graduating class of the National Defense University, to confess his error and apologize. He began by alluding to the suppression of those protesting George Floyd’s murder, saying that the protests reflected not one man’s death but “centuries of injustice toward African Americans. What we are seeing is the long shadow of our original sin… We are still struggling with racism, and we have much work to do.” The acts and patterns of racism and discrimination, said Milley, “have no place in America, and they have no place in our Armed Forces.”

Milley then turned his attention to the events of June 1. “As many of you saw… [there was a] photograph of me in Lafayette Square last week, that sparked a national debate about the role of the military in civil society,” Milley told the graduates. “I should not have been there. My presence in that moment, and in that environment, created the perception of the military involved in domestic politics.” Trump, who had not been informed in advance of Milley’s remarks, was enraged. Within minutes of the conclusion of the speech, Trump’s chief of staff was on the phone to chastise the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, a prelude to the president’s more explosive dressing down of his top military advisor at subsequent face-to-face encounters.

Esper and Milley weren’t the only ones to publically address this incident. Among the most prominent of the critics was one of Milley’s predecessors as Joint Chiefs Chairman, Navy Admiral Mike Mullen, who said the day after the ill-judged photo-op that he felt compelled to break his silence about Trump’s leadership. Whatever his intentions, said Mullen, Trump “laid bare his disdain for the rights of peaceful protest in this country, gave succor to the leaders of other countries who take comfort in our domestic strife, and risked further politicizing the men and women of our armed forces.”

Jim Mattis.

Trump’s former Secretary of Defense, retired Marine Corps General Jim Mattis, weighed in the next day in the pages of Atlantic magazine: “Donald Trump is the first president in my lifetime who does not try to unite the American people – does not even pretend to try. Instead, he tries to divide us… When I joined the military, some 50 years ago, I swore an oath to support and defend the Constitution. Never did I dream that troops taking the same oath would be ordered under any circumstance to violate the Constitutional rights of their fellow citizens – much less to provide a bizarre photo op for the elected commander-in-chief, with military leadership standing alongside.” (See, Jim Mattis, “The full statement from Jim Mattis,” NPR, June 4, 2020.)

The reason that these otherwise relatively minor incidents have such resonance, in addition to them providing an early indicator that the military would not lend itself to Trump’s mutifarious attempts to seize power, is that they’re emblematic of one of the keys of the resistance to a coup attempt. Although it’s rather unfashionable these days to invoke what can be called a “professional ethos,” Esper and Milley represent clear instances of officials holding themselves to a historical standard required by their professional oaths.

What, at least in part, prevented a successful usurping of the Constitution in 2020-21 were scores of people who adhered to the belief that their responsibility to the country’s founding document outweighed their partisan loyalties to individuals and/or parties. What’s more, they understood their professional duties as military leaders, judges, lawyers, teachers, police officers, journalists, election officials, medical personnel, and the like as requiring adherance to the ethos of the profession. That ethos demanded that their actions give precedence to the public interest over self-interest. While we’re admirably quick to identify and publicize cynical breaches of such ethics (and there are always plenty of violations to call out), the crucial upholding of such norms and oaths tend to receive less public recognition.

4.

The birth of Trump’s baseless “Big Lie” about the stolen election had its origins several weeks before the November 3, 2020 vote. On September 23, a reporter asked Trump whether he would commit to a peaceful transfer of power after the election, “win, lose, or draw.” Trump replied, “We’re going to have to see what happens,” and then reiterated his now standard complaint about the questionable legitimacy of mail-in ballots. The brief exchange “represented Trump’s most substantial threat yet to the nation’s history of free and fair elections and prompted election officials… around the country to prepare for an unprecedented constitutional crisis,” write Leonnig and Rucker in I Alone Can Fix It.

The next day, Trump confirmed that he might not honour the results of the election. As he left the White House for a campaign rally in North Carolina, he told reporters, “We want to make sure the election is honest, and I’m not sure that it can be.” Eventually, Trump’s hostility to the otherwise unremarkable mail-in ballot options evolved into the irrational claim that since he was bound to win the election, any other outcome must be the product of electoral fraud. It’s worth pausing a moment to recognize how extraordinary this notion was. The president’s pre-election balking about accepting the election results and his concomitant refusal to pledge that the election would conclude in a peaceful transfer of power was unprecedented, as Max Boot observed (above). So was Trump’s subsequent rejection of the actual vote results after Nov. 3, and his unrelenting attempts to overturn the election, culminating in the January 6 riot at the Capitol.

What’s notable is that so much of Trump’s outlandish behaviour, reinforced by a daily barrage of messages on Twitter, had become utterly “normalised” after nearly a full term in office. Both the public and pundits were long since numbed to its strangeness, which had the cumulative effect of causing even critical observers to accept bizarre utterances, beliefs, and actions as merely a matter of “taking Trump seriously, but not literally.” Polling and other indicators suggested in fall 2020 that there was a likely chance of Trump being defeated by his opponent, Joe Biden. Trump nonetheless asserted that he could not lose the election, and therefore a defeat could only be manufactured through massive voter fraud. Trump’s assertion of certain victory can be written off as hyperbolic campaign rhetoric, of course. But the corollary claim that a loss would be a proof of massive fraud is merely irrational. It rules out the simpler possibility that more people might vote for Trump’s opponent than for Trump. I’m spelling this out in child-like detail only because something like a third of the voting population ended up fervently believing these absurd claims, and did so without any evidentiary support apart from unsubstantiated conspiratorial narratives.

Joe Biden.

In the event, Trump in fact received far fewer votes than his opponent, former vice-president Joe Biden. The popular vote was 81 million to 74 million (or 51.3% to 46.9%), with a 67% turnout, the highest percentage in a century. However, since U.S. elections are determined not by popular vote but by an admittedly antiquated institution, the Electoral College, in which each state “elects” a slate of mediating “electors” (roughly on the basis of that state’s popular vote), it’s possible for a candidate to win the presidency without winning the national popular vote (a result that occurred as recently as 2016, when Trump won the presidency, despite his opponent securing some three million more votes than he).

The system is not only antiquated, but also arcane in that each of the 50 states has a significant degree of autonomy in setting election procedures and of determining election outcomes. As it turned out, Biden also won the Electoral College vote, 306-232 (the same margin by which Trump won the 2016 election) and thus won the presidency. However, the victory was much narrower than appearances suggested, and it was that narrow margin of victory that provided a shred of plausibility to Trump’s subsequent efforts to overturn the election results. In several states (Wisconsin, Georgia and Arizona), Biden’s margin of victory was under 1%, and while it was larger in Michigan and Pennsylvania (both of which Trump had won in 2016), the numbers provided a semblance of contestability. That Biden lost in such key states as Ohio, Florida and North Carolina meant that there wasn’t an Electoral College landslide, which allowed Trump to insist on his big lie of voter fraud, and to persuade his core followers to believe it, for a full year after his defeat, right up to the one-year anniversary of his 2020 election loss, and beyond.

The morning after the Nov. 3, 2020 election, although the final tally of votes and declarations of victory wouldn’t be made known for a few days yet (due to expected counting delays), Trump already knew the likely outcome. “How did we lose to Joe Biden?” he asked his aides. “What happened? What went wrong? Can we still win?” Since there have been persistent questions ever since about whether Trump actually believed there was massive voter fraud or if his Big Lie was merely a cynical concoction for his more rabid supporters, Trump’s day-after remarks to his inner circle might be taken as evidence that the latter is the more likely explanation. But, in the end, it doesn’t really matter if Trump believed his own lies or not, what matters is that he in fact attempted to overturn the legitimate results of the election.

Trump advisor Kellyanne Conway.

The discussion in the White House immediately turned to how to contest the results, such as through court challenges. Kellyanne Conway, Trump’s advisor with the most experience of political campaigns, quickly came up with an uncontroversial message Trump could push on social media: “We want to make sure every legal vote is counted and every illegal vote is not counted.’” It was so unobjectionable that Trump could even demand that Joe Biden retweet it, she suggested. “That’s genius,” Trump replied, perking up. “If we do that, I’ll win.” If Trump had drawn the line at simply exercising his legal right to challenge the results in court, there would have been no problem.

But the point, of course, is that he didn’t stop there. Instead, Trump spent the remaining three months of his term not governing the country but devoting the majority of his time to exploring every avenue for overturning the election outcome, by means both legal and legally dubious. Though urged by various aides and allies such as former New Jersey governor Chris Christie and South Carolina Senator Lindsay Graham to take a “realist” view – i.e., accept the election result, however bitterly – Trump was more receptive to his personal lawyer, former New York mayor Rudy Giuliani, who repeatedly told the president, “They stole this thing.” As Leonnig and Rucker put it, Giuliani “played to Trump’s sense of victimhood and brought any anecdote of alleged voter fraud he could find straight to the president.” They add that, as of November 5, “Trump had his comeback strategy. He would wage a brazen assault on the election, challenging… ballots in courts and trying to pressure judges and state election officials and legislators to stop tabulations” and to even reverse the outcomes.

Military coup in Myanmar.

This is an appropriate place to briefly consider a typology of coups and coup attempts in locating and characterizing the events that occurred in the U.S. between Nov. 2020 and Jan. 6, 2021 (and beyond). Trump’s efforts to retain power should be distinguished from the “classic” military coup which, to take a contemporary example, took place in the southeast Asian nation of Myanmar (formerly Burma) as a result of its November 2020 elections. There, the military, which has a history of periodically seizing control of the country, simply deposed and jailed elected officials, and seized, through force, the major institutions and communications channels of the country on Feb. 1, 2021.

Nazi S.A. “Brownshirts.”

Parallels with the Nazi seizure of power in Germany in 1933 are often invoked in discussions of “Trumpism,” but perhaps it’s more useful to recall the similarities and differences that marked that particular road to dictatorship. Hitler led a legally elected government (we can leave aside the complex details of how the Nazis attained office), as was the case in the U.S. under Trump. However, one enormous difference between the Nazis and American democracy is that the U.S. had a more than two centuries-old historical tradition of government restrained and balanced by constitutional law, norms, and conventions (or “guardrails”), while the Nazis were replacing a relatively unstable social democratic Weimar Republic whose history didn’t extend beyond the end of World War I, when the Kaiser was deposed and fled into exile. Second, and crucially, the Nazi government was backed by a uniformed, efficient, armed party militia in a military situation marked by a weak, almost non-existant national army and the rival, but less effective party militia of the Communists. (Hence, the pertinence of U.S. General Milley’s earlier cited remark, “You can’t do this without the military… We’re the guys with the guns.”) Together, these historical and structural features, and a determined, competent plan, made it relatively easy for the Nazis to decree and enforce an absolutist regime that quickly eliminated rival militia forces, opposition parties, and existing civil rights.

Perhaps a closer contemporary likeness to Trump can be identified in self-declared “illiberal” regimes such as are currently found in Hungary and Poland. There, you have legally elected regimes with enormous majorities who gradually populate the courts with ideological allies, and slowly increase state control of media, while pursuing various “culture war” programs (such as opposition to gays and lesbians, or bans on abortion, or resistance to immigration). Again, in the U.S., the ability to “illiberalize” the regime is restrained by historical norms and popular resistance to extremism. Nonetheless, even in the U.S., such democratic traditions are less stable than advertised. In the year following the January 6 riot, Trump-supporting state governments (Texas provides the most extreme example to date) have passed legislation restricting voter rights (in the name of “election integrity”), banned the teaching of serious discussions of American racism, extended gun rights (in what is already the most heavily armed nation in the world), and severely restricted abortion rights (up to and including full-scale bans).

Technically speaking, what Trump attempted is known (in political science circles, and elsewhere) as a “self-coup,” or autogolpe (in Spansh; in English it’s “autocoup”). It’s a form of coup d’etat “in which a nation’s leader, having come to power through legal means, dissolves or renders powerless the national legislature and unlawfully assumes extraordinary powers not granted under normal circumstances. Other measures taken may include annulling the nation’s constitution, suspending civil courts, and having the head of government assume dictatorial powers.” The classic modern example of a successful self-coup is Hitler’s total takeover of Germany in 1933. (Wikipedia, “Self-coup.”)

The Trump post-election campaign to reverse the election results took several interrelated forms: 1) court challenges to vote counts; 2) pressure on state election officials and legislatures to change state counts in Trump’s favor; 3) attempts to get the nominally independent federal Department of Justice to affirm voter fraud claims; 4) a plan to get Vice-President Mike Pence to reject certification of the Electoral College results at the joint session of Congress on Jan. 6, 2021; 5) the organization of a public rally on the same day that eventually grew into an insurrectional riot by several thousand people in and around the chambers of the Capitol; 6) an unceasing media campaign to persuade people the election had been “stolen,” primarily led by Trump himself; and 7) personnel changes at the defense and security institutions of the government to install Trump loyalists.

Although a couple of the meetings conducted by Trump or his lieutenants might legally qualify as “conspiracies” to overturn a legitimate election or to prevent a legal and peaceful transfer of power, the Trump coup attempt was mostly an ad hoc affair, a matter of trial-and-error attempts to alter the outcome, rather than a competently organized attempt to retain power, backed by substantial armed force. Despite Michael Wolff’s assertion in Landslide that Trump possessed “no ability – or structure, or chain of command, or procedures, or expertise, or actual person to call – to make anything happen,” it turned out there were plenty of actual people to call, and Trump would be on the phone for a good portion of the time after the media’s declaration on Nov. 7 that Biden had won the election. It also turned out that much was made to happen.

While the media was declaring victory for Biden, and the president was relaxing on a nearby golf course that weekend afternoon, the president’s lawyer, Rudy Giuliani, was presiding over a strange press conference at a strip mall in Philadelphia. Trump’s more conventional lawyers, both from his campaign and the White House, were simultaneously humouring the president about his delusional notion of a stolen election, trying to get him to “realistically” recognize the outcome, and at the same time cautiously backing away from direct involvement in the crusade to reverse the results (thus unintentionally clearing the way for the arrival of more eccentric legal and political operators).

Giuliani Four Seasons (Landscaping) press conference.

Meanwhile, Giuliani, who was regarded by several of Trump’s more sober advisers as “frankly, crazy,” was elbowing his way into leadership of the legal campaign. His press conference would prove to be emblematic of the former mayor’s role all the way to the day of the Capitol insurrection where he egged on the rioters, urging “Trial by combat!” The Philadelphia presser was held “in the asphalt parking lot of Four Seasons Total Landscaping… near a crematorium and a sex shop, Fantasy Island Adult Bookstore, where [Giuliani] trumpeted baseless claims of widespread voter fraud.” Obviously, an underling had screwed up the order to book a conference room at the city’s prominent Four Seasons Hotel and the roadshow landed in a location as bizarre as the claims made by Trump’s legal surrogate.

Two days later, Trump turned his attention to the leading figures in his defense and security apparatus. The president’s intention, which he had bruited about before the election, was to fire Secretary of Defense Mark Esper, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Milley, as well as FBI director Christopher Wray and CIA director Gina Haspel, on grounds of insufficient loyalty (to Trump himself) and to replace them with more obedient sycophants. As with so many of Trump’s impulsive and vengeful proposals, this one was scaled back only when advisers pointed out that such a wholesale gutting of the security apparatus would be the ultimate in “bad optics,” and raise questions among international allies about political stability in the U.S. (Indeed, even prior to the election, Esper had authorized Milley to phone international military counterparts, including adversaries such as China, to reassure them of the reliability of American policy commitments. The procedure would be repeated immediately after the Jan. 6 Capitol insurrection.)

Defense Secretary Mark Esper.

On the morning of Nov. 9, Esper attended a briefing at the General Service Administration, where its head was holding up approval for the various departments of government to begin the transition to the new Biden administration, for the spurious reason that the election was still being contested. When Esper returned to his office early that afternoon, his chief of staff immediately informed him of an email reporting that the president was firing him. At the very same moment he received a call from Trump’s chief of staff Mark Meadows, officially informing him of the president’s intention. “We don’t think you’re sufficiently loyal,” Meadows said. The president would announce the termination that afternoon along with the appointment of Chris Miller as his replacement. “Esper thought to himself: Who?” Four minutes later, Trump dismissed Esper with a tweet. Gen. Milley heard the news –having himself received several heads-up that he too was slated for removal – and joined Esper to commiserate. Leaving aside the details of the rest of the day, and the flurry of agitated communications among the upper echelons of government, the main question raised by Esper’s firing and Trump’s thwarted desire to entirely re-staff his military and intelligence agencies with loyalists was, Why?

Why, having lost the election, and with less than three months left to serve as a lame-duck president, was it necessary for Trump to replace his senior defense and security officials with less qualified but more obedient “acting” officials, unconfirmed by Congress? What, exactly, did Trump want “the guys with the guns” to be prepared to do? Among the dozens of people who phoned Milley that day, from House Speaker Nancy Pelosi on down, one “old friend” called to say, “They’re trying to overturn the government… This is all real, man.” Once Milley’s phone traffic from that day alone is perused, it’s indisputably clear that senior figures throughout the government were on high alert. Milley’s attention to coup possibilities was not something the general had made up out of flimsy rumour.

From the tightly woven narratives of both the Leonnig and Rucker and the Woodward and Costa books, with their day-by-day accounts of the scheme to overturn the election, only a few aspects of it, some with possible criminal implications, require more than passing mention here. One particular pattern of occurrences involved repeated refutations of Trump’s “stop the steal” claims, both by individuals and courts. A couple of days after the defense establishment shakeup, on Nov. 12, Arizona reaffirmed its vote count and confirmed Biden’s narrow win there. But each setback only inspired a further thrust by Trump’s campaign team. The next day, Senator Lindsay Graham, at Trump’s behest, was on the phone with Georgia’s secretary of state, Brad Raffensperger, the official responsible for overseeing the state’s election, in a bid to persuade him to somehow intervene in the final count. Graham would later deny any intention other than seeking information about the precise procedures of the vote.

That day, Friday the 13th of November, write Leonnig and Rucker, “was a particularly unlucky day for Trump. It marked the start of a nearly unbroken string of court defeats for him… Many of the emergency legal challenges cobbled together by Trump’s threadbare legal team lacked evidence, failed to state a legal justification… or contradicted one another from state to state.” In short order, Team Trump lost cases in Michigan, Arizona and twice in Pennsylvania. Before it was over, more than 50 U.S. courts rebuffed Trump’s legal challenges.

Nor was the judiciary the only institution discounting the president’s delusions of voter fraud. His own government’s top experts on election security were dubious, too. One conspiracy theory to which Trump was particularly attached was the claim that the Dominion voting machines, widely used across the country, had, as one right-wing media outlet reported in an all caps headline, “deleted 2.7 million Trump votes nationwide.” Chris Krebs, head of the Department of Homeland Security cybersecurity team, responded to one of the president’s subsequent tweets about the alleged fraud that the 2020 election had been “the most secure in American history… There is no evidence that any voting system deleted or lost votes, changed votes, or was in any way compromised.” On November 17, Krebs was terminated with a presidential tweet.

More prominent political figures also rejected the president’s fantasies. On December 14, the Electoral College convened in every state to affirm the election results. The next day, Senate majority leader, Mitch McConnell, who had been among those politely humoring Trump and hoping that Electoral College confirmation would put an end to the “Stop the Steal” campaign, called Biden to formally congratulate the President-elect.

US Attorney General Bill Barr.

Even Attorney-General Bill Barr, one of Trump’s most pliant defenders, eventually abandoned the president. Two weeks earlier, Barr had met with a reporter from the Associated Press and told him that the Justice Department had investigated every credible claim about voting irregularities and that “to date,we have not seen fraud on a scale that could have effected a different outcome in the election.” Trump was, predictably, furious at this betrayal. On the day of the Electoral College meetings, Barr gracefully bowed out as A-G, effusively praising Trump in his resignation letter, and setting his quiet departure date for sometime around Christmas. Trump, undeterred, turned his attention to the final act, Congress’ verification of the Electoral College tally on Jan. 6, 2021, and an accompanying event promoted by the president, a rally of his supporters rejecting the electoral outcome, an occasion that Trump promised his followers, in a tweet, would be “wild.”

The president also continued lobbying state election officials. The most notable of these entreaties was Trump’s call to Georgia’s Brad Raffensperger on Jan. 2. Unlike Lindsay Graham’s earlier call to the Georgia Secretary of State, this one could not be covered up as merely seeking information. The president attempted repeatedly to coerce Raffensperger to “recalculate” the vote to put Trump on top. “All I want to do is this,” the president told Raffensperger. “I just want to find 11,780 votes, which is one more than we have… Fellas, I need 11,000 votes. Give me a break.” As Leonnig and Rucker report, “It was an egregious abuse of power, legal scholars said, and possibly a criminal act.” Indeed, it’s hard to imagine how to hear Trump’s plea as other than importuning a public official to commit election fraud. “There’s nothing wrong with saying that, you know, um, that you’ve recalculated,” Trump rambled on.

Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger.

Apart from politely rebuffing the president’s demand, Raffensperger, a fellow Republican, was prepared to let the incident go, although the conversation had been recorded. However, the next morning, Trump tweeted that he had spoken to Raffensperger and had received unsatisfactory responses. “He has no clue!” Trump’s tweet said, disparaging the Georgia official. That’s when Raffensperger authorized the taped call to be shared with a Washington Post reporter who, later that day, published a story about the conversation, along with the full audio recording.

Just before the events of January 6, Trump embarked on a last desperate plan to overturn the election results. This scheme, which is discussed in the various Trump books, centered on the president’s attempts to get Vice-President Mike Pence, as the presiding officer of the Electoral College vote confirmation ceremony, to simply reject the validity of the votes of several states. What was supposed to happen after that remains a bit fuzzy, but several options were laid out by a conservative lawyer named John Eastman, who had been advising Trump.

Mike Pence (l.).

The most detailed account of the meeting at the White House between Trump, Pence, Eastman and their respective advisers on January 4 can be found in Woodward and Costa’s Peril, published some six months after the Leonnig and Rucker book, but there are no significant differences between the two accounts other than considerably more granular and new information contained in the former.

Eastman, a conservative and respected constitutional law expert, a former law school dean, currently employed on a special project by the Claremont Institute (coincidently, the same rightwing thinktank that employs coup-denier Christopher Caldwell), had come up with an idea that Trump latched onto with obsessive faith. The gist of it, which Eastman laid out in a couple of memos, was, as Woodward and Costa put it, to have “Pence pause the process in Congress [of certifying the Electoral College vote] so Republicans in state legislatures could try to hold special sessions and consider sending another slate of electors [who would vote for Trump].” Eastman drew up various scenarios or pathways that might result in Congress either declaring a delay or even directly pronouncing Trump the winner of the election.

All of the scenarios depended on the cooperation of Vice-President Pence, Trump’s undisputedly most loyal and visible endorser during the previous four years. Pence sought out advice, consulting with his own legal staff, constitutional experts and even former Vice-President Dan Quayle, a fellow Republican politician who, like Pence, was originally from Indiana. All were unanimous in dismissing Eastman’s scheme as being utterly without merit.

Although, as a result of the revelations in Peril, there was some subsequent gossip about Pence’s motivation – was he seeking an escape from his constitutional duties or was he a genuine hero of the moment? – the only important point is that he decided to reject Eastman’s scheme and Trump’s attempts to induce and threaten him into compliance. The inducements and threats were public. At a political rally in Georgia that evening, ostensibly to support Republican candidates for the Senate in a special election the following day, Trump told the crowd of thousands, “I hope Mike Pence comes through for us, I have to tell you. He’s a great guy. Of course, if he doesn’t come through, I won’t like him quite as much.” The president slapped the side of the lectern as the crowd laughed. Everybody got the message… except the addressee.

In the end, Pence decided to stick with the instructions of the constitutional documents: “The President of the Senate shall, in the presence of the Senate and the House of Representatives, open all the certificates and the votes shall then be counted.” He also released a three-page letter the morning of the joint session of Congress on Jan. 6, that explained that the vice-president’s powers were limited to counting, and did not include rejecting, altering, or interfering with the counting of the Electoral College ballots.

John Eastman (l.), Rudolph Giuliani (r.) at Trump rally Jan. 6.

Finally, there’s January 6. Much of what happened at the Capitol was seen live on television and in subsequent videos – thousands of Trump supporters, having listened to fiery rally speeches by Trump and his team, marched down to the Capitol on Trump’s urging, broke windows and doors, violently assaulted the Capitol police, and invaded the U.S. Congress. Vice-President Pence and all the other members of the House and Senate were forced to suspend the verification of the Electoral College results and were spirited away to “secure undisclosed locations” by the battered police, as the mob chanted, “Hang Mike Pence.”

Although much was visible in plain sight, a great deal about the organization, planning, and intentions of the Capitol rioters remains obscure. In the wake of the insurrection, Trump was impeached (for a second time) by the House of Representatives on Jan. 13 and charged with a single article, incitement of insurrection. The impeachment trial in the Senate began on Feb. 9, about three weeks after Trump formally left office, and concluded on Feb. 13 with an acquittal. “At the conclusion of the trial, the Senate voted 57-43 to convict Trump of inciting insurrection, falling 10 votes short of the two-thirds majority required by the Constitution, and Trump was therefore acquitted.” (Wikipedia, “Second Impeachment Trial of Donald Trump,” Oct. 17, 2021.)

It was the largest bipartisan vote for an impeachment conviction of a U.S. president (seven Republican senators joined all Democratic and independent senators in voting to convict), but it hardly answered the unresolved questions of Jan. 6. That’s why Democratic congressional representatives then proposed the creation of a fully bipartisan commission to investigate the insurrection, acceding to almost all stipulations demanded by their Republican counterparts, only to have their “friends across the aisle” ultimately reject the proposal. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi subsequently established a House Select Committee to do the job, and invited opposition party participation. The House minority leader, Kevin McCarthy, obstructively named a couple of rabid supporters of Trump’s Big Lie to the committee, a proposal Pelosi necessarily rejected, which provided an excuse for McCarthy to declare that his party would boycott the committee entirely. In the end, Democrats on the committee were joined by two Republican “dissidents,” Liz Cheney (R-Wy) and Adam Kinzinger (R-Il). Given that the committee has only begun its work, as of autumn 2021, I can refrain from speculation about its eventual findings.

January 6, 2021 on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C. is one of those rare occasions where the famous old kicker, “…and the rest is history,” is truly applicable. History with a capital “H,” and a lot of digital documentation to verify it. The Trump-induced riot took place, several deaths and many injuries (the latter mostly suffered by police officers) resulted from the mayhem, the counting of the Electoral College votes was interrupted for about six hours, the president watched it on TV from the White House, and it took considerable time before he could be persuaded to deliver a video message to tell his followers to leave the Capitol and go home. (See Philip Rucker, “How Trump’s 187 minutes of inaction led to Jan. 6 bloodshed,” Washington Post, Nov. 1, 2021.)

The intention of the insurrectionists has yet to be fully determined. Was it simply to interrupt and intimidate the Congress with the aim of altering their decision; was the riot’s purpose to secure the coerced cooperation of the president of the Senate, Mike Pence; or was the intention simply inchoate? The joint session reconvened that evening and, notwithstanding procedural delays and a sizeable minority vote by Republicans (even after the riot) to reject the certification, the Electoral College vote counts were confirmed. On January 20, 2021, Trump having vacated the White House and flown off to his Mar-a-Lago resort in Florida, Joe Biden was sworn in as the 46th President of the United States.

5.

Woodward and Costa’s Peril concludes with the two-word sentence (mild spoiler alert): “Peril remains.” The reason for reprising the above events and interpretations at length is two-fold. First, there’s simply the intellectual desire to contribute to the establishment of an historically accurate account of events, insofar as that’s possible. As Heather Cox Richardson, the Boston College history professor and author of How the South Won the Civil War (2020), described the stakes in the wake of lawyer John Eastman’s memos to overturn the election, “We now have written proof of an attempt to destroy our democracy and replace it with an autocracy.” She added, “This was not some crazy plot of some obscure dude in a shack in the mountains; this was a plan of the president of the United States of America, and it came perilously close to succeeding.” And in case anyone was having difficulty in grasping the point, she reiterated, “The president of the United States tried to overturn the results of an election – the centerpiece of our democracy – and install himself into power illegitimately.” (Heather Cox Richardson, “Letters from an American, Sept. 25, 2021,” Substack, Sept. 25, 2021.)

But equally important, and the practical reason why the events of Jan. 6 continue to be investigated and to command public attention, is that in the view of many analysts, the coup attempt is not over. As Max Boot put it (cited above), “The effort to minimize and normalize what happened on Jan. 6… is laying the groundwork for a potentially more successful coup attempt the next time around.” Nor are such apprehensions merely abstract.

As neoconservative thinker Robert Kagan noted in a recent widely-read opinion essay, “The amateurish ‘stop the steal’ efforts of 2020 have given way to an organized nationwide campaign to ensure that Trump and his supporters will have the control over state and local election officials that they lacked in 2020. Those recalcitrant Republican state officials who effectively saved the country from calamity by refusing to falsely declare fraud or to ‘find’ more votes for Trump are being systematically removed or hounded from office. Republican legislatures are giving themselves greater control over the election certification process. As of this spring, Republicans have proposed or passed measures in at least 16 states that would shift certain election authorities from the purview of the governor, secretary of state, or other executive-branch officers to the legislature.” (Robert Kagan, “Our constitutional crisis is already here,” Washington Post, Sept. 23, 2021.)

Further, the bills designed to move election certification powers to the state legislature come in concert with a swath of new state laws designed to curtail voting rights, especially of minority groups. No, say the proponents of the laws limiting voting rights, such moves are not in support of Trump’s claims of voter fraud, they’re simply meant to shore up “election integrity.” (Yeah, sure.)

As for General Milley’s remark about “the guys with the guns,” those guys and their guns are hardly confined to the military and the security agencies these days. In their essay, “How Can We Neutralize the Militias?”, Steve Simon and Jonathan Stevenson base their examination of autonomous organized militias in the U.S. on the October 2020 determination, a month before the election, by the Department of Homeland Security that “domestic violent extremists” presented “the most persistant and lethal” threat to the country. (Steve Simon and Jonathan Stevenson, “How Can We Neutralize the Militias?”, New York Review of Books, August 19, 2021.)

Simon and Stevenson duly note that while “Republican partisanship prevented the Senate from convicting [Trump] of ‘inciting violence against the Government of the United States,’” nonetheless, “there is no doubt that Trump harnessed and inflamed an armed and loyal far-right movement – one driven by white supremacist and antigovernment conspiracy theories… — to storm the Capitol” in order to stop Congress’s certification of Biden’s selection as president.

Simon and Stevenson are concerned with both the general tenor of the political situation in the U.S. as well as the existence and growth of right-wing militias. They argue that “the political polarization in the U.S. today is comparable to that during and just after the Civil War. In the U.S., dangers are multiplied by the high level of gun ownership and the ease of purchasing firearms,” which makes the possibility of violence “all the more practicable.” With respect to the practicalities, since 2008, they say, “the number of active groups has increased from 30 to more than 200,” and even a decade ago, “right-wing militia members numbered well over 100,000 nationwide, and their political, recruitment, and paramilitary activity spiked during the Trump administration.” The extensive ties of these militias to members of the U.S. military and to members of various police forces across the country adds to the danger they pose. I mention Simon and Stevenson’s essay not to assess its arguments, but simply to note that the issues they raise have become part of the public agenda of debate and discussion.

The argument that the Trump coup is still underway has been made by dozens of analysts, academics, op-ed writers and others. One representative view can be found in a recent opinion piece by conservative National Review writer Kevin Williamson, who asserts, “What happened at the Capitol on Jan. 6 was not a coup attempt. It was half of a coup attempt… The more important part of the coup attempt – like legal wrangling in states and the attempts to sabotage the House [committee’s] investigation of Jan. 6 – is still going strong. These are not separate and discrete episodes but parts of a unitary phenomenon that, in just about in any other country, would be characterized as a failed coup d’etat.” (Kevin D. Williamson, “The Trump Coup Is Still Raging,” New York Times, Sept. 10,2021.)

Worse, one can’t really pronounce the events, unfolding from the Nov. 3, 2020 election to the Capitol riot on Jan. 6, 2021, as “failed,” given that the attempt is still ongoing. The current efforts to restrict voting rights, and other such measures, says Williamson, has “the obviously political objective… to legitimize the [previous] coup attempt in order to soften the ground for the next one – and there will be a next one.” Williamson sees that, in Trump’s broad strategy, “the frenzied mobs were meant to inspire terror – and obedience among Republicans – while Rudy Giuliani and his co-conspirators tried to get the election nullified on some risible legal pretext or another.” Both parts were necessary. “Neither the mob violence nor an inconclusive legal ruling would have been sufficient on its own to keep Mr. Trump in power.”

Williamson notes that in the normal course of democratic politics, parties who disagree about many issues can often work together when they agree on other issues. “But there isn’t really any middle ground on overthrowing the government. And that is what Mr. Trump and his allies were up to… through both violent and nonviolent means – and continue to be up to today.” Williamson adds, “When it comes to a coup, you’re either in or you’re out. The Republican Party is leaning pretty strongly toward in.”

If Kevin Williamson represents the perspective of non-Trump conservatives about a coup attempt that hasn’t ended, rather similar views can be found at the other end of the political spectrum. Late-night comic Bill Maher, something of a left libertarian, devoted his eight-and-a-half minute monologue on a recent episode of Real Time with Bill Maher to a detailed dystopian description of the “slow-moving coup” that could see Trump return to the presidency in 2024. Maher ended his routine with, “I hope I scared the shit out of you.” (Bill Maher, “The Slow-Moving Coup,” Real Time with Bill Maher, HBO, Oct. 9, 2021; available on YouTube.)