Cuban Postcards

A continent is a landmass. Its coastline, curves, and teeth remember other ancient coastlines that will forever represent lost body parts. A millennial language. But that language was spoken before time could categorize and order it. The languages spoken today sound small patches of identity, reflect indigenous peoples holding tenaciously to the places of their ancestors, cities that speak the conqueror’s tongue, destinations where human beings were traded, sold and sometimes freed.

The American Continent is such a patchwork, from polar north to Patagonian south. Between: the riveting majesty of Grand Canyon, thundering waters of Iguazú, stark desert beauty of Atacama. The secrets of Kiet Seel, Palenque, Tikal. And great modern cities like Montreal, New York, Mexico, Río de Janeiro. Places where anguish and absence are always just below the surface: Santiago de Chile, Buenos Aires, Montevideo, Guatemala. And places where that absence has been redeemed, like today’s Bolivia, Uruguay, or Cuba’s last half century.

Cuba, against every neocolonialist and neoliberal obstacle, chose freedom in 1959. That the Cuban revolution, with all its problems and forced retreats, still stands, is as much a natural wonder as it is the fierce resistance of men and women, a people who continue to respond to no with yes. And within Cuba there is a space called Casa de las Américas, as old and obstinate as the revolution itself.

In the first months following victory, a visionary named Haydeé Santamaría was given the challenge of creating an institution capable of breaking the cultural blockade. Not the military or economic or political blockades, those guns lined up against a tiny island nation, but the more amorphous and ever so much more dangerous efforts aimed at silencing the country’s artists and writers. Silencing ideas, erasing images, in both directions.

Casa stands at the bottom of G Street, close to the malecón, that serpentine sea wall that protects the city from an ocean embracing and threatening simultaneously. It is a three-story gray building, once a synagogue, with a large map of the continent embossed upon its northern face. Inside, galleries, conference halls, and the offices of magazines and research centers contain a living history of cutting-edge thought and artistic production from every reach of the Americas. Haydeé endowed it with courage and wisdom alive long past her death. What has happened at Casa, what happens there still, is nothing less than the powerful magic of creativity and change.

Along with a couple of dozen other writers and thinkers from Bolivia, Guatemala, Argentina, Chile, Spain, Peru, Colombia, Brazil, the United States and Cuba itself, I have been invited to be a judge in Casa’s annual literary contest, known simply as Premio 2011, The Prize. Every year for half a century, literary minds from the Americas have gathered in Havana to read hundreds of entries in the genres of novel, short story, poetry, testimonial literature, theater, critical essay, literature written by Brazilians, inhabitants of other Caribbean islands, and Latinos living inside the United States; and have awarded the prestigious prize to the best in each. I judged poetry in 1970. Now, 41 years later, I have been invited back to judge testimonial literature.

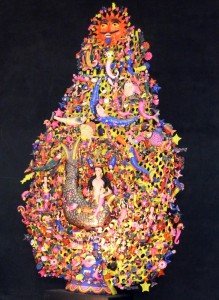

This prize represents so much more than simply choosing the best book and assuring its publication and attendant monetary compensation. Periodically, the institution has used the Premio as a context in which to establish new centers or programs of specialization in such areas as Caribbean or women’s studies. This year the focus is on Culturas originarias de las Américas, native cultures of the Americas. And they really do mean all the Americas, from Canada to the southern tip of the continent. Casa’s library is among the most innovative I have known. Its magazines publish the most exciting new work and retrieve classic texts that would otherwise be lost.

And this is one of Casa’s many strengths: brilliant young people work alongside the old timers who remain. Cycles of tradition and renovation characterize the physical space and all that takes place within it. I cross the threshold and my skin comes alive with an energy difficult to put into words. I am besieged by the faces and voices of those who are gone: Haydeé herself, Rodolfo Walsh, Violeta Parra, Roque Dalton, Carlos María Gutiérrez, Mario Benedetti. I feel their familiar touch upon my arm, a conversation surfaces, an image pushes up. I fight back tears or, in some quiet corner, let them come.

Here, over the next weeks, we will work in the spirit of giants, always conscious of our seriousness and commitment. But also of our defiance and humor. The great debates, achievements, mistakes, and personalities of half a century accompany us.

*

I stand before my old apartment building, trying to recall images of a time more than thirty years gone. Chunks of memory drop away then come crawling back, jostling for a place to stand. I can’t find my old neighbor’s name on the register but hesitantly press the worn tenth-floor button. A voice comes wavering through the rusted speaker. I say my name and hear a faint metallic release as I push against the glass door and step into the vestibule. Suddenly I am three decades younger. I touch the layers of worn fieldstones on either side of the elevator, trying to find the loose one that once covered the place where my children and their friends hid secret messages.

Inside the gray metal box, I notice a surprising absence of graffiti. Thousands of coats of paint, brushed over the walls of this elevator through the years. On the tenth floor, Silvia’s door is open and she embraces me warmly. The interior of her family’s apartment, similar to the one we lived in on the floor just below, begins cracking the dense barrier of time. I find myself wondering about buckets of water collected against frequent shutoffs, a stash of used candle stubs for electrical blackouts, cooking oil poured carefully from a refillable bottle, all the machinations in lives that have weathered the revolution’s ups and downs but have yet to secure that leap of progress for which so many died.

We talk about old times and new, neighbors who are gone and others who still inhabit the eighth floor or the fourth. A son and his wife are there. The last time I saw him he was a child. Now he is a city planner, involved in the magnificent renovation of Old Havana. A thread of genuine caring runs between us, a strong, unbreakable line, dancing from memory to memory, avoiding the entanglements of lives now unfolding in spheres so distant one from the other it would take days or months to retrieve that space in which we might truly inhabit each other’s obstinate hopes and failed dreams.

Later Silvia walks me back to my hotel. A couple dozen blocks shrouded in Havana night. We hold onto each other as we navigate cracked sidewalks and uneven curbs. Groups of young people pass us, arm in arm. A small table where four old men play dominos emerges in a circle of light beneath a rare streetlamp. The 1950s-style building that was a Jewish cultural center when I lived here. Is it still? The hulking Américas Arias hospital, referred to as Maternidad de Línea, where I once had an abortion and so many Cuban women still give birth. We turn down G toward the sea, feeling a rise of moist breeze against our faces.

Now we are standing in front of the hotel. Silvia excuses her home attire and says she won’t come in. We hug goodbye. We will see each other often while I am here, but I will never feel closer to her than I do at this moment, touching the thin woolen scarf she pulls about her shoulders, the one she reminds me I gave her forty years before, when together we patrolled our neighborhood on a night much like this, convinced we were on the winning side of history.

*

Cienfuegos. Middle of the island, nestled along the southern coast. This city was settled by French immigration and many of its buildings conserve their French colonialist architecture and period furnishings never quite at home in this tropical destination. Casa de las Américas has installed us in the Jagua, a four-star hotel situated on a small tongue of land protruding into the bay. I am in my room, watching from my balcony as a last splash of pink fades to night. The phone rings, and the woman’s voice that responds to my “oigo?” wastes no time.

“My name is Rosario Terry García,” she tells me, “your daughter Sarah Dhyana Mondragón Randall’s third grade teacher.” She pronounces all Sarah’s names with perfect recall. “I was fifteen,” Rosario goes on to say, “and Sarah was seven or eight. I was one of the Makarenkos, just starting out.”

I remember the Destacamento makarenko, a battalion of young people who stepped up to fill the vacancies left by so many teachers who emigrated in the revolution’s early years. Boys and girls themselves, with no pedagogical experience and only the training a crash course of weeks or months could bestow. I remember my son, who at eight had a teacher of fourteen who was immensely relieved when his student told him no, masturbation doesn’t really destroy brain neurons as he had warned. In those days teachers and students learned together.

Rosario’s voice cuts through my reverie: “I’ll never forget that little girl—so smart, so beautiful, so active. One day I was teaching Playa Girón, and I saw she was crying. ‘What’s wrong, Child?’ I asked. And she sobbed ‘No, Teacher, it’s the government not the people who attack us!’ And you came to talk to me the next day. I’ve never forgotten that lesson. It’s served me well, through all my years of teaching. But what did we know back then? We were hardly more than children ourselves!”

Rosario had seen my name on the news and tracked me to the Jagua. Time collapsed as it so often does in Cuba, along with crops and infrastructure and the passionate dream of a different world. I want to see her face, embrace her, learn more about this woman who remembers my forty-eight-year-old daughter when she was seven. She says she lives far from the provincial capital, but if I tell her where I’ll be in the morning she will try to find me. I say I’ll be visiting an art school, the Benny Moré. “Why don’t you try to meet me there?”

At the school the next morning I hear a voice calling my name. And there’s Rosario, a heavyset black woman with a broad grin. “Back then I was just a slip of a girl,” she says, no doubt picking up on my appraisal of her appearance. She must think I remember what she looked like. I don’t. I am just very moved by the woman and her story, by the complexity of this web in which both our lives are caught. We talk. We take a few pictures. We hug.

The Benny Moré’s principal asks Rosario how she came by her last name, Terry. It is famous throughout the province for having been that of the plantation owner after whom the city’s gorgeous Teatro Terry is named. “Well,” Rosario laughs, “most slaves got our names from the family to which we belonged.”

When I tell my daughter about Rosario, she remembers nothing. Not the teacher, not the incident. As a child, spending all week at boarding school was unbearable for her, and for many other children of revolutionaries who believed we were changing the world and that our offspring were getting an education based on the values we hoped would launch the new society.

*

Did it fail? The revolution, I mean. And how to measure failure? For fifty-three years it has been pulling itself along, a sack full of stones, a hunch between the shoulders, a garment frayed at the cuffs. Half a century of people wanting only independence, nothing more. Independence from a crude dictator, one of a fraternity at the time. Independence from the puffed up nation to the North, and its swindling mafia of casinos, its crime syndicate of profit over people. Freedom to make the future of its choice.

When I lived here, through the 1970s, life seemed simple. Everyone worked. Health care and education were free. We paid ten percent of our salaries in rent, and after twenty years owned our apartment or home. No matter that someone else had owned it before us, and had fled the Communist takeover sure it would be a matter of weeks or months before they could return and reinsert their key in the lock. Some of those wealthy families hid jewels and silver services in the walls, walls they hoped would remain mute until they could reinstall themselves in mansions or elegant 1950s high-rises.

There were problems, to be sure. The United States has never given up trying to destroy the revolution. Transportation was difficult. Food was rationed, insuring everyone had enough. After a Sunday spent harvesting potatoes in Havana’s greenbelt, Monday we’d find proud pyramids of potatoes at our neighborhood market. Simple, that’s what we said, and smiled. Simple. Knowing class divisions were being eliminated was more important than a varied menu or other luxuries.

In 1989, when the Soviet Union fell apart, Cuba lost its strongest ally. The socialist world disintegrated. Cuba remained defiant, opened to tourism, invested in biochemistry, tightened its belt. There was always Vietnam, then Nicaragua and Venezuela. But the monster to the North regained hegemony and intensified its blockade: a point of attack both painfully real and, increasingly, the excuse for every ill.

Corruption began to corrode. When a construction site or office came up short, it was simply el faltante: that which is missing. Cubans wrote historic pages of selfless internationalism, sending teachers to Nicaragua, medical personnel wherever a natural disaster struck, well-trained professionals to those countries where a new society struggled to gain ground. Some say 10,000 Cubans died in Africa—Angola, Ethiopia, Congo. Some say 20,000. Cubans are proud of their internationalists.

And proud of their generosity, of the shipload of sugar sent to Allende’s Chile when sugar was still severely rationed at home. Of the shipments of coffee and medicines. Of the schools they built for tens of thousands of children from all over the world. But hardship and shortages carried over from one year to the next. Some asked why the country was giving so much away, when the need at home remained so great. Cuba taught the Vietnamese how to cultivate coffee. Now Cuba imports coffee from Vietnam. Something is wrong with the equation.

I walk along the malecón, a rhythmic pulse of waves crashing over the battered sea wall to my left. To my right, blocks of once-elegant buildings, their floors of multiple apartments, gawk broken and sad. Electrical wires strung in haphazard disarray. Clotheslines hung with faded laundry. Home to thousands who have waited in vain for paint, building materials, relief from a ceiling that threatens to collapse or a flight of stairs creaking menacingly beneath the ups and downs.

Further toward the center of the city is Old Havana, whose exquisite renovation, block by block, has made it a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Here the polished cobblestones of some streets alternate with others where upended wooden planks mimic original surfaces. Old houses have been restored to their earlier splendor, with attention to every vibrant detail: the wrought iron balcony, dark woods and tile work, colored glass of the media luna above the door, an old-fashioned pharmacy with its shelves of ceramic jars where one can still fill a prescription or buy a tonic.

This whole area functions as both tourist attraction and neighborhood. People live in these houses. School children study for months at a time in museums of African art. Booksellers stock their open-air stalls with Fidel, Che, an out-of-print novel or maps of the city when it was controlled by the English or Spanish.

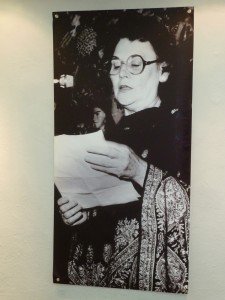

It is Saturday morning, and I am at the beautiful Plaza de Armas, waiting for Mirta Yáñez’ book launch to begin. The book is a novel, Sangra por la herida. Its author describes it as settling scores for dozens—or hundreds—of talented artists and writers who suffered during what Cuban intellectuals refer to as el quinquenio gris, the gray period. That period, from the late sixties to mid seventies, wasn’t confined to five years, and it was a good deal darker than gray for those who opted to emigrate, or who ended their own lives when faced with the shameful repression.

There aren’t enough chairs for the crowd that has gathered for the book’s presentation. I catch sight of dozens of old friends but also see many young faces in the crowd. There is an atmosphere of anticipation. Around a small table in front, Mirta is flanked by her publisher, a critic—people there to introduce the book.

The publisher opens the event, then Mirta reads an impressive passage. I look around. There are tears in many eyes. During the launch, several exotic figures appear and position themselves behind the presenters: a mime painted in silver, a woman holding a straw hat and large sunflower. The silent tableaux speaks of significance and tribute.

When the formal reading ends, I get up and approach one of the two tables toward the back where stacks of the novel are for sale. “How much?” I ask. “Fifteen Cuban pesos.” “No, How much in CUC (convertible currency, an effort to rein in the black market).” “We’re only selling the book in Cuban pesos.” “Please,” I beg, “all I have are CUC.” And a chant goes up: “Sell her the book, sell her the book!” “One CUC,” the salesperson finally agrees. Less than a dollar.

*

After the demise of the socialist bloc, Cubans pulled their belts ever tighter and suffered through a Special Period in Peacetime. There was less of everything. Blackouts were scheduled and daily. Thousands of bicycles took the place of cars that broke down or whose drivers couldn’t buy gas. Those were the 1990s. Nineteen-ninety-three was the hardest. Gradually production went up, yearly GNP increased impressively, and life got better. A little bit better.

Today when I ask people if they think the nineties will return, everyone says no. Yet five hundred thousand State workers began being laid off at the beginning of January. People are being forced to accept the fact that work is no longer a given, a right guaranteed by the socialist State. The Cuban workforce was grossly inflated, three or four people doing one job, and no one’s salary was really enough to live on. Thus the mass-scale ingenuity, whereby people devised all sorts of creative ways of getting by.

Some people will retire. Many are being encouraged to establish small private businesses. A friend tells me three cafes have sprung up on his block in just the past month. But these enterprises need capital. I can’t see Cuba’s banks being able to extend the necessary credit. Investment will have to come from outside the country, and undoubtedly much of it will come from the exile community. These economic transfusions will certainly bring with them troubling quotas of power and influence.

My old friend is a sociologist. He has long been involved with a group whose job it is to analyze the country’s problems and suggest policies aimed at solving those problems while preserving some of the revolution’s gains: shelter, food, free education and health care, culture and sports. To what does he ascribe this failure, I ask. “Two things,” he says, “trying to go to fast, and the paternalism of the State.”

Going too fast. Yes, I remember a time early on, when some idealists believed Cuba would be able to create a communist state without going through the socialist phase. The goal was rooted in the fervent desire for a society based on justice. But the world got in the way. And today none of the isms offer a complete answer. The internationalization of greed makes those long-ago dreams seem utopian.

And then there’s the paternalism of the State: a ruling party that makes all the important decisions, allows citizens’ input only to a point, tightly controls information and isolates or punishes those who dissent. The problem isn’t that people must conform to a Party line, but that their innate creativity has been dulled. Every once in a while a passionate people stand up and demand explanations, answers, apologies. But half a century of authoritarian rule—even while making a genuinely better life for many—has robbed Cubans of initiative. Their sense of real agency has been suppressed.

I link paternalism with patriarchy, a failure to challenge the conventional distribution of power.

*

While I am in Cuba someone mentions a news story about the Pope urging people not to use “unusual names!” I wonder: unusual by whose standards? Perhaps the Catholic pontiff hopes to encourage the use of names from the old or new testaments. I don’t know how children are named in Africa or Asia, what rules apply in the Arabic world. In Egypt and Jordan I met a great many Mohammads. And Jesús and María are popular throughout the Spanish-speaking countries.

In Cuba unusual names have proliferated, since the revolutionary victory and before. I remember early on hearing about a girl called Usnavy—U.S. Navy. Her parents were intrigued by the letters they saw on the underside of the wings of a North American military plane.

When I lived here, the president of our block committee was a jovial black man from Camaguey. We always called him by his surname, Masa. His wife was Elena, but their daughter was Krupskaya. One of my poet friends is from a community deep in the countryside at the eastern end of the country. His parents had named him Bladimir, after Lenin, spelled just like it sounded to their ears.

Children’s names often reflect their parents’ heroes, and if an idol falls from favor the namesake suffers. Lenin remained popular for boys, more so than Vladimir. But I won’t forget three brothers in exile from the Dominican Republic. Their names were Stalin, Lenin, and little Mao. In Cuba the youngster, especially, was in for a tough time—as if being in exile without their parents wasn’t enough of a burden!

As beauty aids and other consumer items disappeared from the shelves of Cuban stores, nostalgia developed for certain brands and their names came into favor. Miladys and Ivorys are two I remember. Adding the s at the end seemed to be the twist that made a product name fit for a human being.

Cuban magic realism is unique to the island. The Pope would have a hard time imposing his plea against unusual names here.

*

After fifty-three years—eleven of which I shared in everyday bus stop waits and lines outside the fried rice restaurant, and after a half-dozen return trips—I find I have a single question: why did some Cubans leave and others stay? I’m not so interested in the stark ideological differences, nor in those more amorphous reasons such as tedium or exhaustion. I want the answers hiding beneath the answers, that complex fabric of emotions, decisions, choices that finally tips the balance in one direction or the other.

To leave or not to leave, a long dilemma. The first waves of emigrants were the super rich, whose expectations and lifestyles went beyond mere class. The sugarcane magnate who resettled in Peru, only to find himself facing another nationalization. The Bacardi family, whose elegant mansion was turned into a clinic, where my youngest daughter awaited her parents’ arrival. All up and down Miramar’s lavish Fifth Avenue, homes once belonging to the wealthy were transformed into boarding schools, where at five each weekday afternoon doors opened and thousands of children of all ages and skin-shades ran shouting and laughing between dorms and dining halls. Before the revolution, if you were a black child in those neighborhoods you could only have been the son or daughter of a maid or gardener.

People kept leaving, first sure they would be back in weeks or months. Then that conviction fell apart, and they made their lives outside, complete with organizations dedicated to the destruction of this political process that in their sense of things had robbed them of life as they knew it. There was Operation Peter Pan through which parents who believed the wild rumors about children being taken from their families, sent them to the United States in care of Catholic Charities. Many of those children were all but orphaned, not to be reunited with a mother or father for decades.

There was the Camarioca boatlift in 1965, followed by the so-called Freedom Flights that lasted until about 1972 and brought some of the first waves of Cuban emigration to Miami, New Jersey, and elsewhere. Two hundred sixty thousand refugees is a figure often quoted. And the United States granted these refugees special status, guaranteeing them residency and citizenship. One confluence of events after another provoked the major exoduses: 125,000 marielitos in 1980, the balseros who sailed from Cojímar in 1994. Until there were a million Cubans living off their island. Ten percent of the population: not as much emigration as produced by a whole lot of other countries, but clothed in a hysteria that inflates the numbers.

The U.S. and Cuban governments engaged in their calculated games of chess. Sometimes one side was caught off guard, sometimes the other. But the chess pieces were human beings, with illusory hopes, a desperation that sometimes outweighed fear, resentments and, too often, sorrows no one could really decipher. Much of what has been published about these great human migrations has been little more than an attempt to justify one side or the other.

Fought against extraordinary odds, the Cuban revolution nurtured a bristling pride. One had to place it at the center of one’s life, support it against all odds, agree with its tenets, trade silence for argument, let go of or hide religious belief, be willing to embrace a routine in which dissent was not permitted and travel didn’t exist. Being forced to defend a single ideology, combined with the daily sacrifices implicit in creating a society that works for everyone, made many feel like outcasts in their own land. As families were torn apart, this too became a factor. How could a mother contemplate never again seeing her son or daughter? How could a child reconcile never again embracing a mother or father?

For years, those who left were called gusanos (worms), and battered by repudiation on their way out. In 1980 I looked out my ninth-floor windows and witnessed mobs gathered in front of the homes of those whose names were on the exit lists: sneers, spittle, rotten eggs. To what did this rage respond?

If a person who made the choice to leave had up until then assumed a revolutionary self-righteousness, one might understand a degree of resentment. Opportunism rarely leaves a pleasant taste in the mouth. But why the mob scenes aimed at ordinary citizens, who simply decided they wanted out? What emotions of their own were the batterers hiding?

I remember the shame I felt, and also the unspoken expectation that if you supported the revolution you naturally took part in those painful demonstrations. When the time came for their cowering targets to be transported to boat or plane, police escorted them courteously, protecting and keeping them safe. It was easy for those of us who supported the revolution to argue the repudiation was spontaneous emotion, not official policy. But the atmosphere was one of hate. Couldn’t the revolution just as easily have prevented those scenes in the first place?

For much too long, Cubans on the island were encouraged to break with their relatives who left. Telephone calls were difficult. The Voice of America’s blatant propaganda painted a picture of idyllic life in the North. Even letters were frowned upon.

In time, the true spirit of revolution won out, and this crass rigidity was tempered. Cubans on the island, comfortable in themselves, with nothing to prove and nothing to hide or of which to be ashamed, pushed for better relations with Cubans outside the country. More thoughtful members of the diaspora initiated contact with those who stayed. The Cuban Communist Party relaxed some of its more exclusionary rules, such as denying membership to those with religious beliefs. People began traveling back and forth; the audacious color snapshots of full refrigerators and late model cars gave way to a more realistic storyline. And some U.S. administrations were slightly less belligerent than others with regard to the small island nation to the South. No U.S. administration has had the intelligence or courage to dismantle the blockade. But both governments found ways—some public, some less so—to obtain what they needed from each other.

The word gusano is an echo, never far from my ear. How many times, during the years I lived here, did I myself use that ugly epithet? What currency did it offer? Why did I think that if I wasn’t out there on the front lines, I was somehow absolved of blame? It’s been a while since I’ve heard anyone who emigrates labeled a worm. Gusano. Those six letters continue to prick at my consciousness, begging exploration or redemption. In my synesthetic mind they should be a dark silvery blue, but streaks of bilious yellow run through them, rivers of nausea and shame.

Now, thirteen years after my last visit and fifty-three from the revolution’s birth, I ask everyone I believe might have something to say. What do you think makes some Cubans leave their country and others remain, faithful beyond expediency? Not the obvious reasons—a worldwide wanderlust, aging relatives abroad, the perception of greater professional success or an easier middle-class life? No, it’s the other reasons I’m looking for, deeper and less easy to decipher.

Several friends tell me they think it’s about personal space. If they are committed to the revolution and have a minimal geography of privacy and movement, people aren’t so likely to want to go. Those who are forced to share their living quarters with too many others, even perhaps an ex-spouse or aging parents, may be more inclined to give up and emigrate. I ask my question again and again, and one after another refers to the importance of space. An ample map upon which to stretch, move, hide, and be who we are called to be.

More profoundly, I suspect it has to do with a deep love of country and culture, an identity that depends on place for full expression. Or, alternatively, on what another beloved figure of the diaspora, Lourdes Casal, once called “a marginality immune to all returns.”

Yuca al mojo de ajo. Ron añejo. Platanitos. Even chícharos, that staple that has become the stuff of so many jokes. El son matancero. Changó. Yemeyá. Oyá la Furiosa Patrona. Waves breaking over the malecón and ocean as far as you can see. Landscapes both wild and gentle. And always those beaches with their stands of Royal palms. Images, smells, sounds, tastes. Bits and pieces of an answer impossible to translate.

Perhaps my question comes too late, or has become irrelevant. Today so many leave and come back to visit without the strictures of years gone by. It is in this coming and going that the fabric of an answer is woven.

Sonia Rivera-Valdés is a writer and professor of Caribbean literature who was born in Cuba and emigrated to New York because she didn’t like the revolution. She wasn’t a child taken by her parents. She knew her own mind. And then, through the years her mind changed. Her path and the revolution’s crept towards one another until they touched and finally embraced. Earlier she had joined a group of exiles beginning to question their initial assumptions. In time, the necessary opening arrived and she boarded a plane.

Since then, Sonia has made many trips back to the country of her birth. In the context of the literary event in which we are both judges, I notice people sometimes refer to her as Cuban-American, sometimes as a Cuban living in the United States. But she always calls herself Cuban. She speaks of her first trip back: “When I left Cuba I left a house. No one took it from me, but when I returned it was inhabited by a family with lots of kids… and I was happy. I realized there was no room for resentment.”

When asked why she, in contrast with so many exiled Cubans, hasn’t gone the way of resentment, Sonia says: “Maybe because they haven’t lived, like I have, the experience of a little girl in Peru asking me what a book is for, because she didn’t know what it was, she’d never seen one. In the context of how complex this process of five decades has been, a process in which I too have lived through many difficult moments, stories like that say it all.”

On this visit Sonia receives a phone call more startling than the one I received in Cienfuegos, and discovers a half-sister she never knew she had. In the grand scheme of things it’s a brief history, after all, that has erected these barriers, this pain. The longer fuller history allows Cubans to claim their heritage wherever it is they live.

.

Spring, 2011