Ashes and Embers

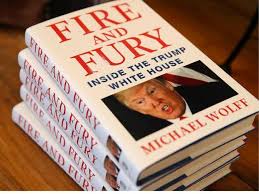

Michael Wolff, Fire and Fury: Inside the Trump White House (2018).

1.

Most of the fire and fury about Fire and Fury, Michael Wolff’s mega-best-selling portrait of the chaos inside the Donald Trump White House, has died down since the book was published in January (although the chaos itself is far from having died down). Like much else in the blur of the accelerated Trumpian news cycle, things tend to fall victim to instant amnesia these days.

Michael Wolff’s “Fire and Fury.”

Yet, for a full week at the beginning of 2018 (it was only three or so months ago – hard to believe, eh?), Wolff’s tell-all was on the front page/screen of every major newspaper/digital site in the U.S. It’s probably the first time a book has commanded that much journalistic attention since Charles Dickens published serialized newspaper versions of his newest novel and devout readers supposedly lined up on the docks of New York to await the arrival of the ship bearing the latest cliffhanger installment.

Given that the American president has seemingly speeded up time, I thought it might be interesting to take the opposite approach and slow down the inexorable stream of Chronos-and-consciousness. Rather than reacting to Michael Wolff’s book in the immediate over-excited fuss about its revelations, how about giving it a belated second look? Rather than the president’s always-impulsive instant reactions, what about some “slow thinking” (as psychologist Daniel Kahneman’s catchphrase has it), considering Wolff’s book in subsequent tranquillity, say, three or four months later, when it too has been pretty much forgotten? Of course, under Trump there is no “subsequent tranquillity,” but let’s try.

Actually, talking about Fire and Fury’s “revelations” is the wrong term; maybe “confirmations” is better, since Wolff’s main aim is to pull together all the fragmented journalistic claims of White House dysfunction (chaos that Wolff had witnessed first-hand as an on-site West Wing observer) and let readers know that most of the things they’d heard about the Humpty-Trumpty White House were true. Wolff is attempting a quick sketch of personalities and rivalries, internecine staff warfare and foul-mouthed late-night rants, shifting coalitions and presidential whims (including cheeseburgers). Wolff is not a policy guy, and it would be wrongheaded to fault him for failing to discourse learnedly, say, on the debate to repeal and replace former president Barack Obama’s health care policy, “Obamacare.”

You want policy, you want political theory? Well, for the Happy Few (thousand), there’s David Frum’s contemporaneous Trumpocracy: The Corruption of the American Republic (2018) or David Cay Johnston’s It’s Even Worse Than You Think: What the Trump Administration Is Doing to America (2018). As of mid-April, there’s also former FBI Director James Comey’s A Higher Loyalty (2018), the first insider participant version of the story (see Michiko Kakutani, “James Comey Has a Story to Tell. It’s Very Persuasive,” New York Times, Apr. 13, 2018). And, no doubt, there are dozens more in the publishing pipeline. But for the disgruntled millions, it’s Fire and Fury, complete with lipstick-stained gossip, that provides a quick initial glimpse.

Despite the obviousness of how high or low (mostly low) to set the bar for Fire and Fury, quite a few competent book reviewers have been surprisingly snooty about Wolff’s million-copy gossipy expose. My favourite local online paper headlined it, “A Bad Book About a Worse President,” complaining that it “relies on a Trumpian approach in which facts don’t matter.” Masha Gessen, last year’s National Book Award non-fiction winner for The Future is History: How Totalitarianism Reclaimed Russia, said that Wolff’s “instant best-seller is part old news, part bad reporting. Its success is symptomatic of our degraded sense of reality under Trump.” (Crawford Kilian, “A Bad Book About a Worse President,” The Tyee, Jan. 9, 2018; Masha Gessen, “Fire and Fury Is a Book All Too Worthy of the President, New York Review, Jan 7, 2018.)

Now, of course, I’m not claiming that Fire and Fury is a great book, or even a very good book. What strikes me about it is that it just might be good enough to accomplish its aims for the readership it’s seeking to reach. And that’s something that its disdainful critics don’t seem to get.

I suppose that all the disdain for Fire and Fury’s tattle-tale author and, by implication, its destined middle-to-lowbrow readership, is understandable enough. After all, Michael Wolff is neither an all-star TV news anchor like CNN’s Wolf Blitzer, nor even a peer of such prominent print journos as New York Review of Books political analyst Michael Tomasky, or the Rolling Stone’s Matt Taibi (author of Insane Clown President: Dispatches from the 2016 Circus). Wolff’s a middle-rank grinder who does (occasionally fawning) political profiles for the likes of Hollywood Reporter.

Wolff’s just a guy, by his own account, who hung around the White House. He’d done a “soft” HR piece on Trump in 2016, and after the election, in New York, asked the president-elect if he could come down to Washington and be an observer. Trump thought “I was asking for a job. I said, ‘No, no. I might want to write a book.’ His face fell. He was completely uninterested. So I pressed a little. I’d really like to do it. So it was, ‘Yah, yah. OK, sure.’” (Trump, of course, later denied everything.)

Visitor logs at the White House record Wolff checking in more than 20 times during the first half-year or so of the new administration. “I went in with the inclination to seem like a journalist with purpose but you lose that when literally everyone is ignoring you,” Wolff said. “You really become part of the furniture, this guy who is so pathetic, people really make an effort to entertain you.”

“Then they’d say, ‘Who are you waiting for?’ Often that would be Bannon, who’d never ever keep an appointment. So they go, ‘Uh uh yeah, wanna come back?’ Suddenly you’d find yourself in the chief-of-staff’s office.” And that’s pretty much how Michael Wolff got his scoop of the year. (Edward Helmore, “’It’s all explosive’: Michael Wolff on Donald Trump,” The Guardian, Jan. 14, 2018.)

Masha Gessen, who I otherwise admire as a writer, is particularly sniffy about Wolff’s insta-book. In effect, she asks, What’s the big deal? “The President of the United States is a deranged liar who surrounds himself with sycophants,” she points out. “He is also functionally illiterate and intellectually unsound. He is manifestly unfit for the job. Who knew? Everybody did.” (Mmm, I’m not so sure… everybody?) Her point is, So why do we need Michael Wolff’ to paw the table scraps and record the potty-mouthed denunciations to get the picture? Not so much real fire and fury, as mere “sound and fury, signifying nothing,” as one Shakespearian-inflected critic put it.

Speaking of table scraps, Wolff’s narrative begins, appropriately enough, at a toney private dinner in a Greenwich Village townhouse in New York on Jan. 3, 2017, just two weeks before the inauguration of Donald Trump as 45th president of the United States.

Clams and Arctic char were on the menu (according to Edward Helmore’s subsequent interview with the author), and the guest list featured two major right-wing media figures. “The evening began at six-thirty,” Wolff reports, “but Steve Bannon, suddenly among the world’s most powerful men and now less and less mindful of time constraints, was late.”

Steve Bannon (l.), Roger Ailes (r.)

Bannon, the former campaign manager of Trump’s thoroughly unexpected presidential win, and senior strategist-designate for the Trump White House, had rocketed to prominence from his previous role as CEO of a fringey, far-right media outlet, Breitbart News. “Bannon had promised to come to this small dinner arranged by mutual friends,” Wolff notes, “… to see Roger Ailes, the former head of Fox News and the most significant figure in right-wing media and Bannon’s sometime mentor.” (Michael Wollf, “Prologue: Ailes and Bannon,” Fire and Fury, 2018; Edward Helmore, loc. cit. above.)

Actually, it was a kind of goodbye dinner for Ailes. While waiting for Bannon to show up, Wolff provides readers with a mini-sketch of the 76-year-old Ailes, the former CEO of Fox News, who had recently been fired by the mainstream right-wing media outlet – international media mogul Rupert Murdoch’s flagship American vehicle – for the crime of sexual misconduct, or at least credible allegations of same. The believable claims – often documented in pay-off deals, but seldom prosecuted in court — would be sufficient, in due course, to sweep out various Fox on-air personalities, as well as scores of other high-profile employees at other networks, Hollywood studios, academia, publishing, and just about every other field of endeavour in the country.

The charges would also lead to a renewed public movement – appearing under such labels as “Me, Too” and “Time’s Up” – against sexual assault and for women’s equality in the workforce. The high-tide of the story wouldn’t break until October 2017, shortly after Wolff’s reportage wraps up but before the book’s publication, with a particularly egregious case of serial sexual assault involving Hollywood studio boss Harvey Weinstein. Understandably, Wolff doesn’t have the luxury of focussing on subsequently important political-social thematics – that’s simply one of the occupational hazards of writing this sort of on-the-fly political travelogue. So, Ailes, for the moment, was simply a slightly disgraced old letch on his way the next day to a Palm Beach, Florida retirement, rather than an incipient emblem of a possible large-scale cultural shift.

Eventually, “at nine-thirty, three hours late, a good part of the dinner already eaten” – but the baba au rhum dessert presumably not yet served – “Bannon finally arrived. Wearing a disheveled blazer, his signature pairing of two shirts, and military fatigues, the unshaven, overweight, sixty-three-year-old joined the other guests at the table and immediately took control of the conversation.”

What follows is a more or less verbatim account of Bannon in full rhetorical flight, both teeing up the White House (“Tillerson is two days, Sessions is two days, Mattis is two days…” he said, ticking off the confirmation hearings for cabinet appointees) and carving up the world (“Day one we’re moving the U.S. embassy to Jerusalem. Neytanyahu’s all in,” and “Let Jordan take the West Bank, let Egypt take Gaza. Let them deal with it,” and anyway, “China’s everything. Nothing else matters. We don’t get China right, we don’t get anything right.”).

In addition to offering up the tabletalk of the behind-the-scenes-powers-to-be, and describing the passing of the torch of populist Republicanism from the cashiered Ailes to the ascending, further-right nationalism of Bannon, Wolff is also letting us know in the prologue that this is a “present at the creation” moment of the new presidency. It’s also, as Wolff profiler Edward Helmore puts it, “the creation story of a book that demolish[es] illusions about Donald Trump’s improbable White House.”

One of the main reviewer criticisms of Wolff’s book has to do with “sourcing.” For example, as critic Jonathan Martin puts it, Wolff is “slippery about whether he was present for some of the conversations he relays or is merely offering a version of events from those who were. He opens the book… with an engrossing dinner conversation that included Bannon and Roger Ailes… offering sentence after sentence of verbatim quotations. Wolff writes that the dinner was held ‘in a Greenwich Village townhouse,’ but leaves out that it was his home and he was the evening’s host…” (Jonathan Martin, “From ‘Fire and Fury’ to Political Firestorm,” New York Times, Jan. 8, 2018).

True, in describing the dinner as merely “arranged by mutual friends,” Wolff unaccountably forgets to mention that he was the “mutual friend” who hosted the dinner, a small fact that would nonetheless be useful to note, since it would support the authentication of the quotes he provides. In this instance, it may be as much an editing error as anything else. Given the speed of the book’s production, and that its publication date was pushed forward once its pending appearance became known in the press (and White House lawyers threatened the publisher with cease-and-desist letters, which were defied), maybe it’s just a minor glitch.

Still, it’s also the case that there are few other sources cited throughout the text, although it’s clear that Bannon himself is Wolff’s main man when it comes to reporting on the internecine warfare within the White House. And much of what we learn comes through those “anonymous sources” we’ve become accustomed to in reading the reportage about Trump’s inner circle.

One thing worth noting about those anonymous sources extensively utilized not only by Wolff but by such mainstream media (MSM) as the Washington Post, New York Times, and CNN, is that they’ve turned out to be pretty reliable. When various MSM outlets announced in advance of the event that Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, or any of a score of other officials, was about to be fired, the media may have been a bit off on the timing (since timing is mainly a matter of presidential whim), but time and again the journalists and their shadowy informants have been on the mark. Since it’s fashionable to be dismissive of MSM these days (with a lot of help from a president who calls the media the “enemy of the people”), it’s only fair to also register how remarkably industrious and, as it turns out, accurate they’ve been in reporting the internal White House turmoil.

Perhaps more to the point regarding Wolff is that though he’s been widely chided for amateurism, it’s the case that, as far as I know, no one has denied any of the quotes or views Wolff attributes to them (except perhaps for Trump, and he doesn’t count, given his public record of fabulation). Apart from minor typos, no one has come forward to show that Wolff has gotten anything substantial wrong. I see little here that reflects a “Trumpian aproach in which facts don’t matter,” or just plain “bad reporting,” or even justification for dissing the book as being merely “symptomatic of our degraded sense of reality under Trump.”

Wolff says, in effect, it’s a madhouse, it’s Beverly Hillbillies Go to Washington, it’s a Tweetpit (with super-sized fries). And he’s not only mostly on-target, he was also the first to put the story together in book form. His aims may be limited to “demolishing illusions about the improbable Trump White House,” as one critic put it, but maybe that’s good enough for a first draft (or first re-write) of history. Why begrudge him earning a few millions bucks for getting it right?

A last word on the attribution problem, as it’s known in the journalism business. As Wolff says (and there’s no reason to doubt him), shortly after the inauguration, “I took up something like a semi-permanent seat on a couch in the West Wing. Since then I have conducted more than 200 interviews.” More important than whether Wolff was a Zelig-like fly-on-the-wall at various White House occasions is Wolff’s own point that “many of the accounts of what happened in the Trump White House are in conflict with one another; many, in Trumpian fashion, are baldly untrue. Those conflicts, and that looseness with the truth, if not with reality itself, are an elemental thread of the book.”

2.

Rocket Men: Donald Trump (l.), Kim Jong Un (r.)

Fire and Fury takes its title, fittingly, from a Trump remark made in early August 2017. He and North Korean dictator Kim Jong Un were taunting each other, mostly in a volley of tweets in which Trump referred to the North Korean as “Little Rocket Man,” while the leader of the “Hermit Kingdom” claimed that “I will… tame the mentally deranged U.S. dotard…” Somewhere in this undiplomatic duel, Trump promised to annihilate Kim’s regime in a rain of “fire and fury, the likes of which the world has never seen.” While the mutual linguistic pyrotechnics were exploding, it was possible to forget that two world leaders were talking about ending that world through nuclear war. Google reported that the exchange prompted a spike in queries for the term “dotard” (which according to the Oxford dictionary is “an old person, especially one who has become weak or senile”).

Notwithstanding its apocalyptic title, Wolff’s book is actually about the unstable, narcissistic personality of the American president and the fairly vicious squabbles of his henchpeople and enablers. Of course, such internecine warfare could not only generate a rain of fire and fury, but could reduce a fragile world to ashes and embers.

Wolff begins with a reconstruction of election day (and evening) in November 2016 from the point of view of the Trump campaign, most of whose members, including the candidate, were absolutely convinced that they were about to lose, hoping only to keep the defeat “respectable” in terms of the percentage point spread. That gives readers a first glimpse of the narrative’s main characters. There’s Trump and his spouse Melania, a former fashion model. There are the final campaign bosses, Steve Bannon and Kellyanne Conway, brought in along with substantial money from reclusive billionaire donor Bob Mercer, a computer scientist and hedge fund operator (who was the money man behind a data-crunching firm called Cambridge Analytica). There are “the kids” – daughter Ivanka Trump and her husband Jared Kushner, and two other sons who will handle the family business while dad is running the country. And then there are the many players who have by now mostly come and gone: former chief of staff Reince Priebus, former National Security Advisor Mike Flynn, former press secretary Sean Spicer… and a cast of hundreds. All reduced to ashes and embers.

Wolff is useful enough on the profile stuff; however, among the glaring analytical shortcomings, there’s no account whatsoever of Trump’s win. No sorting through the exit poll results to find out which demographic groups were crucial to the victory; no honing in on the key electoral states in America’s rust belt where Trump squeaked out less than one per-cent margins to win (but one per cent or less was all that was needed); indeed, no sense at all of how narrow Trump’s triumph was (a matter of, maybe, a few thousand votes here and there); and no use of those facts to underpin the variety of theories that emerged to explain the victory. Perhaps Wolff’s intended readership is completely disinterested in explanations and theories, and thus experiences no sense of anything missing. Still, it might be helpful to notice that those middle-aged and elderly white men without college educations — but not impoverished — living in rural America’s heartland towns, who voted 72-24 per cent for Trump over Hillary Clinton, were the demographic skeleton key to the next presidential administration.

From election night, Wolff heads over to the hub of the president-elect’s operation, Trump Tower in New York. “Trump’s instinct in the face of his unlikely, if not preposterous, success was the opposite of humility,” Wolff tells us. “It was, in some sense, to rub everybody’s face in it.” Suddenly, there was a stream of job-seekers, petitioners, wannabe advisors and hangers-0n paraded through the marbled foyer of the branded tower, as the paparrazi-style media jostled for an angle, until the apprentice pilgrims disappeared behind the gilded elevator doors and were whisked to the sanctum. “Trump forced them to endure what was gleefully called by insiders the ‘perp walk’ in front of press and assorted gawkers.”

Wolff’s shrewd point here is that “the otherworldly sense of Trump Tower helped obscure the fact that few in the thin ranks of Trump’s inner circle, with their overnight responsibility for assembling a government, had any relevant experience. Nobody had a political background. Nobody had a policy background. Nobody had a legislative background.” Eventually, Trump would rely on a team of military men, and the media types he regularly watched on Fox TV in the mornings, who inspired him to compose stream-of-consciousness tweets with which to bombard social and journalistic media.

One brief anecdote Wolff tells neatly encapsulates what would be an ongoing dilemma. Shortly after the election, according to Wolff, Roger Ailes advised Trump, “You need a son of a bitch as your chief of staff. And you need a son of a bitch who knows Washington.” He added, “You’ll want to be your own son of a bitch, but you don’t know Washington.” Ailes had a suggestion: former Speaker of the House, John Boehner. “Who’s that?” asked Trump. As Wolff implies, that pretty much tells you all you need to know about the president-to-be’s state of ignorance.

I needn’t reprise the White House narrative in extended detail. Much of it has long-since faded in the welter of outrageous moments that followed in the succeeding months. Who now remembers “Day One,” when Trump, “not taking off his dark overcoat, lending him quite a hulking gangster look,” visited the Central Intelligence Agency? “Pacing in front of the CIA’s wall of stars for its fallen agents… disregarding his text, [Trump] launched into what we could confidently call some of the most peculiar remarks delivered by an American president”?

The off-the-cuff rambling speech was strangely disconnected, boastful (about his own intelligence, his campaign and the crowds that attended – or, as it turned out, didn’t attend – his inauguration the day before), which then segued into an attack on the media (who were apparently responsible both for under-reporting the size of the crowds and for intimating that Trump was quarreling with the intelligence branch of the government), and included a non-sequitor proposal to seize oil in Iraq, and something about America “winning” something or other. What Trump didn’t mention was that wall of stars commemorating fallen U.S. agents, or the fallen agents themselves, or anything else that might be apropriate to a presidential visit to the country’s intelligence agency.

If Day One wasn’t so great, it might be worth recalling that Week One produced a presidential order banning entrance into the U.S. by the citizens of seven countries with Muslim-majority populations. The order was promptly suspended, at least temporarily, by the first court given a chance to rule on its constitutionality, but not before it created a good deal of short- and longer-term chaos, and successfully transmitted a signal of ethnic and religious bigotry. If nothing else, the First Days provided a perfectly accurate template of what daily rule by Trump would be like, not only through Wolff’s six-month journalistic tour, but well beyond.

Wolff touches, however lightly, on most of the issues, from a Supreme Court appointment, to Russian aggressions, a U.S. reprisal bombing in Syria against dictator Bashar Al-Assad’s use of chemical weapons, healthcare debates, the firing of FBI director James Comey to stymie the investigation of Russian interference in the American election, all the way down to a casual executive order banning transgender people from serving in the military. In between, there are countless bizarre and often petty episodes, and almost every chapter focuses on the inner White House struggle for power, a sort of multi-table ping-pong contest. Some days it was Bannon against Trump’s kids, or the chief-of-staff against Bannon, or the president against his Attorney General, and whatever other available permutations of the long-running who’s-in-charge-here debate.

3.

Where Wolff comes out is not so far from the scathing assessment of Trump by Masha Gessen above (“a deranged liar who surrounds himself with sycophants”). Late in the book, discussing the impending firing of Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, Wolff remarks that the Secretary’s “fate was sealed – if his obvious ambivalence toward the president had not already sealed it – by the revelation that he had called the president ‘a fucking moron.’”

Wolff points out that “this—insulting Donald Trump’s intelligence—was both the thing you could not do and the thing—drawing there-but-for-the-grace-of-God guffaws across the senior staff—that everybody was guilty of. Everyone, in his or her own way, struggled to express the baldly obvious fact that the president did not know enough, did not know what he didn’t know, did not particularly care, and, to boot, was confident if not serene in his unquestioned certitudes.”

Wolff adds that “there was now a fair amount of back-of-the-classroom giggling about who had called Trump what.” For both Secretary of the Treasury Steve Mnuchin and Chief of Staff Reince Priebus, Trump was an “idiot.” For Gary Cohn, an investment banker who headed the National Economic Council, he was “dumb as shit.” General H. R. McMaster, the National Security Advisor, thought the president was a “dope.” As Wolff notes, “The list went on. Tillerson would merely become yet another example of a subordinate who believed that his own abilities could somehow compensate for Trump’s failings.” With the exception of the Treasury Secretary, all of the above noted underlings are now gone, along with dozens of lesser figures.

In a later interview, Wolff cautiously approached even darker matters about the president’s mental health. He said, “I don’t know if the president is clinically off his rocker. I do know, from what I saw and what I heard from people around him, that Donald Trump is deeply unpredictable, irrational, at times bordering on incoherent, self-obsessed in a disconcerting way, and displays all those kinds of traits that anyone would reasonably say, ‘What’s going on here, is something wrong?’” (Helmore, loc. cit. above.)

While Wolff may not be very good on policy matters, such as healthcare, I think he’s more than adequate in portraying Trump’s indifference to policies and legislation. “Trump had little or no interest in the central Republican goal of repealing Obamacare,” Wolff flatly declares. “An overweight 70-year-old man with various physical phobias (for instance, he lied about his height to keep from having a body mass index that would label him as obese), he personally found health care and medical treatments of all kinds a distateful subject.”

Hence, “the details of the contested legislation were, to him, particularly boring; his attention would begin to wander from the first words of a policy discussion… and he certainly could not make any kind of meaningful distinction, positive or negative, between the health care system before Obamacare and the one after.” Wolff quotes Roger Ailes as saying, “No one in the country, or on earth, has given less thought to health insurance than Donald.”

Oddly enough, Wolff suggests, Trump was “rather more for Obamacare than for repealing [it]… In fact, he probably favored government-funded health care more than any other Republican. ‘Why can’t Medicare simply cover everybody?’ he had impatiently wondered aloud during one discussion with aides, all of whom were careful not to react to this heresy.”

Wolff, as critics have noted, devotes barely a line to the Senate debate on repealing and replacing Obamacare, which concluded with Republican Senator John McCain providing a dramatic thumbs-down gesture defeating his own party’s proposal. But Trump’s own distracted attitudes to such policy matters, while hardly justifying Woolf’s approach, goes some way to explaining it.

Like other members of the choir of commentators writing during the period Woolf’s book covers, I, too, was interested in the “illusion of the improbable Trump White House,” and with issues involving the distortions of time, memory, attention spans, and the coarsening of civic life that Trump had so affected. From his spurts of personal rage delivered through early morning tweets, to his challenge to conventional understandings of truth and lies — even reality itself — the epistemological crisis was compelling.

I recall writing an op-ed piece at the beginning of August 2017 in which I observed that, “if nothing else, the one thing we can say about the Age of Trump is that it’s utterly exhausting… Just trying to keep up with the soap-opera plot twists, multiple storylines and dizzying reversals in any given week is almost enough to defeat any desire to record it.” (Stan Persky, “Monday Monday: Keeping Up with the Trumps,” Dooney’s, Aug. 5, 2017.)

I then launched into – at about the same time as Michael Wolff was wrapping up his reportorial fieldwork – a longish catalogue of just the events of the last week of July of that year. They ranged from big issues such as Trump publicly threatening to fire his Attorney General, Jeff Sessions, and vacantly attending to the healthcare debate (referred to above), to such lesser matters as an apparently drug-fuelled, obscenity-laced, over-the-top phone call to a reporter (armed with nothing more than a digital recorder) from Trump’s newly appointed communications secretary, one Anthony (“the Mooch”) Scaramucci. Oh, and there was also a harangue before the Boy Scouts of America, a ban on transgender members of the military, the firing of Trump’s chief of staff, and his replacement by General James Kelly, whose first act was to fire the aforementioned director of communications. All of this was duly noted in service to the moral of my op-ed story: “Each time you think it can’t get any worse, any more bizarre… it does.”

Six months later, as I was giving Michael Wollf’s book a second look, the New York Times’ headline for March 23, 2018, was “After Another Week of Chaos, Trump Repairs to Palm Beach. No One Knows What Comes Next.” It was followed by another breathless journalistic effort to recount the president’s week, “after a series of head-spinning decisions… that left the capital reeling and his advisors nervous about what comes next.” It’s not too hard to see why “chaos” is a plausible thematic. (Mark Lander and Julie Hirschfeld Davis, “After Another Week of Chaos…”, New York Times, Mar. 23, 2018.)

Perhaps, as Masha Gessen suggests, “everybody” already knew all this. Everybody, that is, except for the 63 million people who voted for Donald Trump (46 per cent of the electorate). For Wolff’s million-plus readers, whether or not they already knew Trump was an “idiot,” encouraging them to keep in mind the depth of the president’s ignorance, as Wolff does, is probably a good thing.